Hacks on Louisiana Parishes Hint at Nightmare Election Scenario

Hacks on Louisiana Parishes Hint at Nightmare Election Scenario

(Bloomberg) -- James Wroten called the clerk of court in Vernon Parish, Louisiana last November with an urgent message.

The timing wasn’t convenient. The clerk, Jeffrey Skidmore, was relaxing on his back porch and hoping to soak in some final moments of quiet before state and local elections. Skidmore let the call go to voicemail.

But Wroten, whose company manages IT services for small companies and local governments, persisted until Skidmore finally picked up.

“He told me we’d been infected by ransomware and to ask all 14 of my employees not to go into the office or try to access any of their files,” said Skidmore. “I was stunned. We had an election in six days.”

That call, Wroten later recalled, was the start of one of the worst weeks of his life. Hackers had infiltrated Wroten’s company, Need Computer Help. From there, the attackers used the connections Wroten’s employees need to do their job in order to breach the networks of Vernon Parish and six other local parishes, the Louisiana equivalent of counties.

The attacks highlight how vulnerable local jurisdictions remain despite four years of efforts to shore up defenses in preparation for the 2020 presidential election. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has repeatedly warned about the risk of ransomware before the upcoming vote. A cybersecurity expert hired by Wroten believes the attacks on Louisiana’s parishes were purposefully deployed just before the election.

Although no election systems were directly impacted, the attack placed enormous stress on local jurisdictions at a critical time. The same attackers also infiltrated other Wroten clients, including local courthouses, sheriffs’ offices and companies in finance, health care and manufacturing between Louisiana and Texas, using relatively easy to obtain malicious code known as Sodinokibi, which has been dubbed the “crown prince of ransomware.” (The cybersecurity firm Coveware Inc. said in a 2019 report that Sodinokibi had been targeting IT managed service providers through a variety of software vulnerabilities).

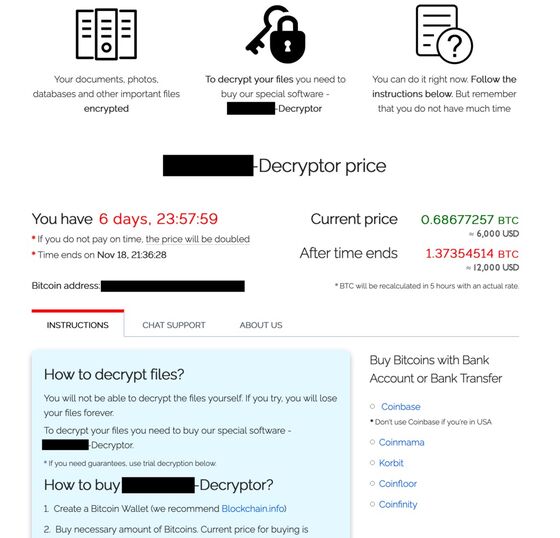

While targeting local voting authorities in rural Louisiana may not be especially lucrative to hackers, ransomware attacks -- which lock up files with encryption until the victim pays a specific fee -- are capable of disrupting voter registration, voting and tabulation, according to federal authorities. Even if hackers time criminal attacks to elections because they believe the added pressure might get officials to pay faster, a wave of well-timed attacks could still create a cloud over results -- just as the recent malfunctioning of an app used to transmit caucus data did in Iowa.

The ransomware attack on the parishes came just before an apparently unrelated hack of the state of Louisiana’s computer networks. Just days after a contentious Nov. 16 election, the winner, incumbent Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards, announced that state computer networks had suffered a massive ransomware attack, shutting down email communication and paralyzing the Office of Motor Vehicles, among other critical agencies.

But details on the earlier attack hitting local governments have emerged only recently. A forensic review, including computer logs tracking the hack, were made available to Bloomberg News, and they reveal a key detail: Even though the hackers had been in the system for four months, they waited until just before Election Day to launch the attack.

Jason Ingalls, a Louisiana-based breach response specialist, was hired to review how the hackers broke into the network and what they did while inside. He’s concluded that the hack was more than a mere coincidence.

“We believe it was executed at that time on purpose,” said Ingalls. “They had been in the environment for months prior and decided to pull the trigger a week before the election. Weeks later, the state was attacked too. If this was a test, it creates a very dangerous model for discrediting election results.”

Ben Spear, director of the Elections Infrastructure Information Sharing and Analysis Center, or EI-ISAC, dubbed such attacks “stropportunistic” -- an attack strategically focused on collecting ransom that also presents opportunities for additional malicious activity. The EI-ISAC is a conduit between the federal government and local election authorities for securing election systems and responding to breaches and vulnerabilities.

Details of the attack can be pieced together from Wroten’s computer logs. The attackers infiltrated Wroten’s network on July 23 at 3:17 p.m. but did not execute the ransomware until 11:10 a.m. on Nov. 10. As Wroten began to appreciate the magnitude of the attack, he contacted Ingalls, who’d previously helped governments and private entities recover from ransomware attacks. Among Ingalls’ experience was negotiating with hackers on the dark web who demanded payment in Bitcoin in exchange for providing a decryption key.

In this case, the attackers wanted $3.5 million from all the victims, including the parishes and private companies, Ingalls said.

In the six weeks after the attack, Ingalls took inventory of the encrypted data and identified those files that couldn’t be restored without payment. That included a district court’s recordings of a murder trial ending in conviction and sentencing, and family photos an employee of a private company had stored on a professional device.

Ultimately, he said he negotiated the ransom down and cobbled together enough cash to unlock those 20 computers that required decryption for recovery. He declined to say how much the hackers were paid, or what individual victims contributed.

Wroten’s company, Need Computer Help, wasn’t completely lacking protection, Ingalls said. The company had invested in antivirus software and firewalls, updated its programs and backed up all its data. But when hackers acquired credentials to access the network, none of those protections were of any use. The malware was too sophisticated to be detected by antivirus and firewall protections, and the backup system was compromised in the same way the rest of the network, he said.

“What we’ve got here is a bunch of people using Revolutionary War equipment to defend themselves against fighter bombers from Russia,” he said. The hackers haven’t been identified, though law enforcement is continuing to investigate. Ingalls said the malicious code was configured to shutdown any attack on a system where the keyboard corresponds to Russian or other Eastern European languages, a possible clue to where the hackers originate.

The credentials the hackers acquired yielded access to software that Wroten’s company had licensed from a third party provider, ConnectWise, to remotely manage his clients’ IT systems. ConnectWise said in a statement that Wroten’s firm hadn’t adopted enhanced security protocols, like multifactor authentication, offered by the company to defend against such attacks.

“The product thus performed as designed and was misused by these threat actors with stolen credentials,“ ConnectWise said in a statement, adding that it’s now in the process of making multifactor authentication mandatory for all clients using its Automate services.

The use of managed IT service providers such as Wroten’s by local governments has grown as public budgets have shrunk, especially among city and county governments, according to state and local officials. And that budget consciousness may be part of the problem.

Wroten estimates 80% of Louisiana parishes administer IT tools using remote service providers. While there’s no data on how many voting jurisdictions across the U.S. rely on remote IT, election administrators estimate around 50% of the more than 7,000 voting districts in the U.S. use managed service providers.

After last year’s attack, Wroten embraced updated cyber defense tools to protect his network, adding multifactor authentication and threat detection systems. But providing these new services to his clients has forced him to increase costs by 20%. Since then, he’s lost business, with about 5% of his clients going elsewhere or possibly skipping IT services altogether.

”Many of these jurisdictions have two choices because of their budgetary constraints: remote access IT support or no IT support,” said Louisiana Secretary of State Kyle Ardoin. “Quite often, they choose the latter and pay for services as needed. For some, security has been an afterthought.”

The state is now embarking on a 30-day assessment with the Federal Bureau of Investigation to understand the depth of vulnerabilities across parishes and state departments, Ardoin said.

“No one can ever say for certain 100% that their network is secure,” Wroten said. “Given the amount of malware and ransomware activity going on within government and private networks on a regular basis, there’s a very high risk that jurisdictions will have to take the time to wade through these kinds of attacks before credibly certifying their results in 2020.”

--With assistance from Jordan Robertson.

To contact the reporter on this story: Kartikay Mehrotra in San Francisco at kmehrotra2@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Andrew Martin at amartin146@bloomberg.net

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.