Gulf Cash Fuels Fight for Muslim Hearts and Minds in Africa

Gulf Cash Fuels Fight for Muslim Hearts and Minds in West Africa

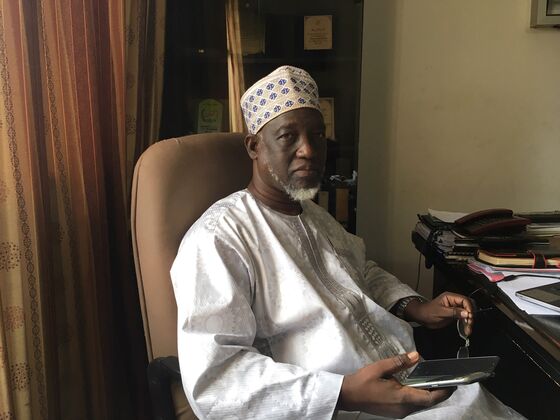

(Bloomberg) -- Ibrahim Kontao is busily signing checks as men and women line up outside his air-conditioned office in the Malian capital, Bamako, to ask him for donations and help with their children’s school fees.

Kontao, who studied theology in Saudi Arabia, heads Mali’s wealthiest Islamic charity, known as Al-Farouk, which channels $3 million a year from donors in Gulf Arab states and Turkey to open mosques, Koranic schools and health clinics in rural areas starved of social services. Critics say it and other groups are championing the stricter Wahhabi school of Islam that inspires al-Qaeda- and Islamic State-affiliated militants who claim attacks across West Africa.

“They gain people’s trust by taking care of their needs,” said Brema Ely Dicko, the 36-year-old head of the Social Anthropology Department at the University of Bamako. “Today you see women wearing niqabs, something that used to be very foreign to Mali.”

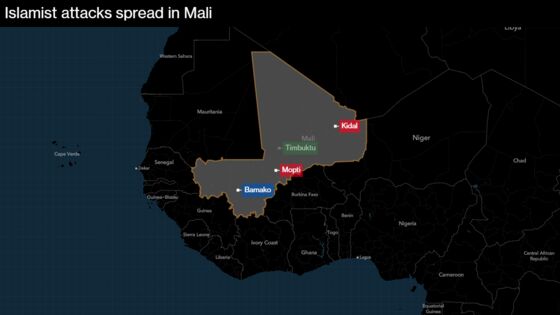

Mali teetered on the brink of collapse when a loose alliance of ethnic Tuareg separatists and Islamist insurgents, bolstered by an influx of weapons from Libya, seized the north in the wake of a 2012 coup that left the army in tatters.

Timbuktu Attacks

The militants shocked the international community with a series of attacks in Timbuktu on the centuries-old buildings with tombs of holy men, turning sites into piles of rubble because they were considered idolatrous by the insurgents. The International Criminal Court, in an unprecedented ruling in 2016, jailed the leader of the raids for nine years.

Despite the deployment of a 15,000-strong United Nations peacekeeping mission and a French military force, jihadist attacks have spread to Mali’s center, resulting in the deaths of hundreds of troops and civilians.

The insecurity has spilled over into Burkina Faso, Niger and Ivory Coast and prompted the creation of a 5,000-strong West African force that’s to strengthen border patrols. Saudi Arabia itself has joined the battle against the militants, pledging 100 million euros ($113 million) to the force known as G5 Sahel.

President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita’s government has failed to maintain basic services in remote rural areas as it focuses spending on the military. That’s where the Gulf-backed charities step in to offer an alternative to the state.

“Many people are struggling; I want to do what I can to help,” said Kontao at the Al-Farouk charity. “We’re always building schools and mosques. I don’t know how many mosques we’ve built, but it’s hundreds.”

Lack of Oversight

Yet the lack of oversight over mosques and schools and the increasing Wahhabi influence over politics and daily life is fueling concern that militant groups may take advantage to expand their reach.

Thierno Amadou Diallo, who’s in charge of the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Worship that was set up in 2012 to counter radicalization, said the government doesn’t know how many mosques there are even in Bamako.

“The state has little control over what the religious leaders tell their congregation or the curriculum taught in the thousands of religious schools spread across the country,” Diallo said in an interview. “When the state doesn’t fund the mosques, it becomes very difficult to control them.”

His ministry was set up as counterweight to the Islamic High Council and its president, Mahmoud Dicko, 64, a well-known Wahhabi.

Political Influence

Muslim leaders have long vied for political influence in Mali, one of the poorest countries in the world. In recent years, they’ve publicly thrown their weight behind presidential candidates, helped raise foreign donor money, halted bills aimed at strengthening women’s rights and mediated talks between the government and insurgents.

Moderate Muslims like Cherif Ousmane Madani Haidara, the Islamic High Council’s 63-year-old vice president, are trying to counter what they see as the harmful Wahhabi influence. He’s so far sponsored 500 students to complete a two-year training program at a Moroccan government school for clerics in Rabat that includes instructions on how to argue against calls for jihad.

“Islam is a tolerant and peaceful religion,” he said in an interview as he sat on a white leather couch underneath a portait of him together with Morocco’s king, Mohamed VI. “But just like the jihadists, these imams try to persuade young people that jihad and terrorism will give them benefits in paradise.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Katarina Hoije in Abidjan at khoije@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Karl Maier at kmaier2@bloomberg.net, Pauline Bax, Michael Gunn

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.