Europe Tamed a Populist and Now He’s Paying the Price

Michalis Asikis and his brother aren’t your typical shoe-store owners, at least by most standards.

(Bloomberg) -- Michalis Asikis and his brother aren’t your typical shoe-store owners, at least by most standards. One uses time away from the shop to teach at a music school while the other heads off to taxi tourists.

In Greece, though, scratching a living from multiple sources isn’t unusual nowadays. The struggle to make ends meet or keep businesses on life support has become the norm for many Greeks, despite the promise by Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras that “hope is coming” when he surged to power in 2015. Indeed, to avoid shuttering his store in the northern town of Florina, Asikis has resorted to borrowing from family.

“People believed in Tsipras’s central slogan and not only didn’t hope come, there was also great disappointment,” Asikis, 47, says at his outlet on Florina’s main commercial street, which is littered with empty stores. “It’s like telling a kid that you will get them an ice cream and ending up giving them nothing, not even chewing gum.”

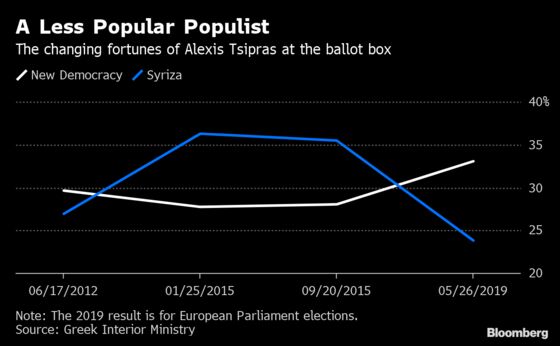

Such disillusionment is the harsh reality for Tsipras as he heads into elections on Sunday. While he managed to restore faith in Greece internationally, he lost it at home as his fresh face came to represent more of the same to a jaded nation. Opinion polls show power is likely to return to New Democracy, one of Greece’s two traditional parties of government, and back to the dynastic politics that Tsipras and his Coalition of the Radical Left vowed to break.

To European Union leaders like German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Tsipras is the tamed populist who took the country to the brink and then ultimately saw sense and assumed responsibility.

He agitated to abandon Greece’s bailout and then did a deal with creditors before guiding the country back into investors’ good books. He courted Russia only to act against Moscow’s interests in the Balkans by ending a decades-old name dispute over what’s now called North Macedonia, an aspirant EU and NATO member that Vladimir Putin would prefer to keep in his orbit.

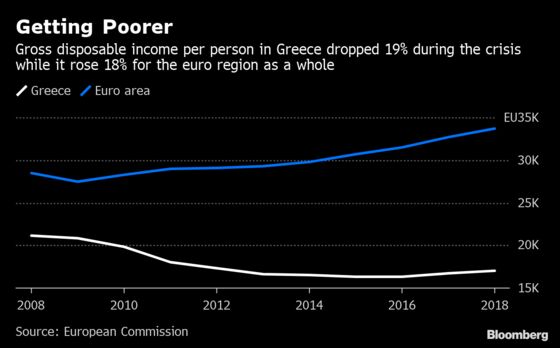

But to many Greeks he was a sell-out as they endured a financial crisis that started in 2010. He caved to the demands of creditors for more spending cuts and tax increases, failed to cope with the influx of refugees and sparked protests over the Macedonia deal. Meanwhile, the economy went back into recession just when it was about to start growing again and has failed to meet growth targets since.

“It’s more a matter of him being forced to learn certain realities,” said Kevin Featherstone, professor of contemporary Greek studies at the London School of Economics. “The old promises were no longer credible, he’s had to move on. The ‘black sheep’ turned ‘white.’”

Florina in the western part of Greece’s Macedonia region encapsulates the meteoric rise of Tsipras and now the decline. Placed at the country’s northern border, surrounded by mountains, the town of about 18,000 people is known for its heavy winters, brown bears and red peppers. Locals rely on the state and the ailing Public Power Corp. SA, Greece’s largest electricity provider, for their livelihoods.

The unemployment rate of almost 30% is among the highest in Greece and Public Power is struggling. Auditors in April questioned the company’s ability to continue operations after it lost more than 500 million euros ($538 million) in 2018.

A traditionally more conservative area, Florina put its trust in Tsipras in the election that swept him to power in January 2015 after he had transformed his party, known by its Greek acronym Syriza, from the margins into an electoral machine. Voters gave him a second chance in September that year, even after he capitulated to creditors’ demands following a referendum where more than half the population rejected the terms of Greece’s bailout agreement.

Tania Grammatikou, a 45-year-old civil engineer who lives in Florina, said she never bought Tsipras’s story. For all his initial grandstanding, such as urging people to vote against the bailout, life was getting harder. She earned 2,500 euros a month before the crisis working for the state. It abruptly dropped to 1,000 euros with the crisis and she feels like she’s been in “limbo” for much of the past decade.

“During the last few years I have clashed with most of my friends who rooted for Syriza,” she said. “Since he was willing to deliver everything that was being asked of Greece, of course he’s widely respected outside the country. He didn’t manage to support his fairy tale, the one that Greek people were more than happy to believe in.”

Grammatikou said she voted for Pasok, which dominated politics along with New Democracy before it was crushed as a political force by the crisis and the surge in support for Syriza. Not unusually in rural Greece, most people declined to say how they voted because everybody knows everyone in the town. All agreed that the “hope” was short-lived.

Fixing a country that had lost a quarter of its economic output was never going to be easy, especially for a leader who promised to increase salaries and pensions and reduce taxes.

The economy still has the highest unemployment rate in Europe. Greek banks are saddled with bad loans totaling 80 billion euros. Some 4 million taxpayers—equivalent to 37 percent of the population—owe the state 104 billion euros in back payments, more than three times the level before the crisis that started in 2010. Educated young Greeks are still departing for western Europe.

Rather than halt the austerity measures he blamed for enslaving a nation, Tsipras was forced to continue them to keep Greece afloat through lifelines provided by European creditors and the International Monetary Fund.

The first increase in the Greek minimum wage didn’t come until February this year, and only after the country had exited the bailout program he had initially sought to abandon.

Yet in many ways, it’s a huge achievement to have lasted this long—and it might be foolish to write him off, though polls show New Democracy has a nine percentage point lead over Syriza.

Tsipras rode out five no-confidence votes in parliament to endure more than any Greek prime minister since the onslaught of the country’s financial crisis. The anti-austerity street protests that caught global attention before his election vanished while he was in power. Greece returned to financial markets and now pays marginally more than Italy to borrow based on 10-year bond yields.

He earned more kudos abroad. He sealed an agreement with Greece’s neighbor in former Yugoslavia over the name “Macedonia,” a long-standing gripe of Greeks who blame the country for misappropriating their history and culture from the Alexander the Great era. By renaming the country the Republic of North Macedonia, Greece ended its block on membership of the EU and NATO. New Democracy opposes the agreement.

An EU official in Brussels described Tsipras’s political journey as a “deep transformation” that turned Europe’s enfant terrible into a trustworthy partner. His relationship with Merkel flourished.

She appreciated his efforts to deal with the influx of refugees using Greece as a door to the EU and to end the Macedonia name dispute, an official in her Christian Democratic Union party said. The person, who declined to be identified when talking about the dynamic between the two leaders, said Germany considers Tsipras to have stabilized Greece.

“That lesson of compromise, seeking consensus and credibility, spilled over into foreign policy and the agreement on ‘North Macedonia’,” said Featherstone, the academic in London. “This was a real breakthrough.”

Grammatikou, the civil engineer in Florina, said the deal was the one bright spot, although many of her fellow residents accuse Tsipras of betraying the country’s heritage.

Vasilis Pantelidis, 37, who identifies as a proud Macedonian, is one of them. He took part in the mass protests in the summer of 2018. Tsipras was caught on camera during a European leaders’ summit calling participants extremists of the right and nationalists. That enraged people in the north even more, said Pantelidis.

“You can’t just go out and call anyone who disagrees a fascist,” he said. “This affected a lot of people. It offended them, people of all political colors.”

It also added salt to his financial wounds from the crisis. Pantelidis, an economist, returned to Florina from Athens in 2015 in the hope that Public Power, whose vast brown coal lignite mines dominate the area, would be championed by Syriza and start hiring again.

Instead, Public Power is trying to sell two lignite powered plants that correspond to about 40 percent of its capacity following demands by Greece’s creditors for the company to reduce its market share. Meliti I, one of the two, is among the largest employers in the Florina region and the move is opposed by workers.

“The crisis has left me behind with everything,” he said as he took a sip of his iced coffee in the sunshine at a cafe by Florina’s river bank. “How can you start a family when there’s insecurity? My work contract finishes in a year and what happens after that? Our most productive age is from 25 to 50 years old. Half of mine is gone with the crisis.”

Back on the town’s main shopping thoroughfare, shoe-store owner Asikis has a similar outlook. Revenue has plunged 80 percent during the crisis. People just can’t afford the high-end brands he sold so easily during the times of Greek largess before 2010. Many drive across to North Macedonia to do their shopping and fill up their cars.

“Nothing is left to cover daily needs,” Asikis said. “We are always looking for new ways to cover our expenses.” His brother is currently working on the tourist island of Santorini ferrying tourists to and from the airport to make better money.

“Syriza couldn’t change the climate,” he said. “The worst part is that they brought additional disappointment.”

--With assistance from Sotiris Nikas, Birgit Jennen and Viktoria Dendrinou.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rodney Jefferson at r.jefferson@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.