Just $27 a Week Is Lifeline for Millions in Coronavirus Britain

A drop in welfare payments called Universal Credit could see millions of people lose out on aid.

(Bloomberg) -- As well as a straining health system and policing of lockdown rules, Britain’s financial response to the coronavirus pandemic is in the spotlight again as more families risk slipping into poverty.

A drop in welfare payments called Universal Credit could see millions of people lose out on aid from what’s already one of the developed world’s least generous systems. That’s after the government’s free school meals program sparked another row this week as images on social media showed the limited contents of packages that Manchester United soccer star and campaigner Marcus Rashford called “unacceptable.”

The U.K. has spent more than 280 billion pounds ($384 billion) fighting the economic impact of Covid-19, providing support for businesses and furloughed workers. But Prime Minister Boris Johnson is coming under increasing criticism from charities and political opponents for not going far enough, and leaving decisions till the 11th hour.

Some of the nation’s poorest stand to lose 20 pounds a week in Universal Credit in April should an emergency increase not be extended. While the government has said it’s an issue for the March budget, the uncertainty is already having an impact on spending as people worry about paying the bills, according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

“Twenty pounds a week of income is the difference between going to a food bank or going to a supermarket,” said Rebecca McDonald, senior economist at the group, which focuses on poverty. “It’s the difference for some families between having their heating on, and their lights on, or not.”

The issue of Universal Credit has become all the more important because it’s the only safety net available for many of the estimated 3 million people who have found themselves excluded from other support packages.

The Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimates that 6.2 million families would lose income if the uplift is removed, pulling 200,000 more children into poverty. The Legatum Institute think-tank reckons 690,000 more people have been pushed into poverty by the pandemic already, a number that would have been doubled without the extra money.

Johnson’s press secretary, Allegra Stratton, said on Monday that ministers will “take a judgment in due course” on whether to extend the extra money. “There’s still some time,” she told reporters. “We understand the importance of this to many families.”

The prime minister on Wednesday suggested extending the uplift isn't a priority. Asked whether it’s “unfair” to wait until March to make a decision, he told a House of Commons committee that the government wants to see jobs.

“We want to see people in employment, we want to see the economy bouncing back and I think most people in this country would rather see a focus on jobs and growth in wages rather than focusing on welfare,” Johnson said. “But clearly we have to keep all these things under review.”

The approach is emblematic of Britain’s economic response to the pandemic, which won praise in the early days but has now drawn criticism for descending into firefighting. Last year, the government’s furlough plan was extended on the day it had been due to end, while an eviction ban, which had been due to end on Monday, was only extended last Friday.

One of the people excluded from the pandemic support is Ester De Roij, a Bristol-based wildlife filmmaker. She saw three shoots, equating to nearly 20,000 pounds of work, canceled overnight when last March’s lockdown began.

Having only set herself up as a sole trader in 2019, she was unable to draw on the aid for the self-employed, and has since relied on Universal Credit, supplemented by help from her family and temporary work with the Post Office. The extra money might not sound a lot, but losing it would mean she risks not being able to pay her landlord, she said.

“At the moment I can cover rent and I need to find money from somewhere else and pay for food,” said De Roij. “But if that gets taken way then I can’t afford to live where I live. For me that’s the difference between having a roof over my head and not.”

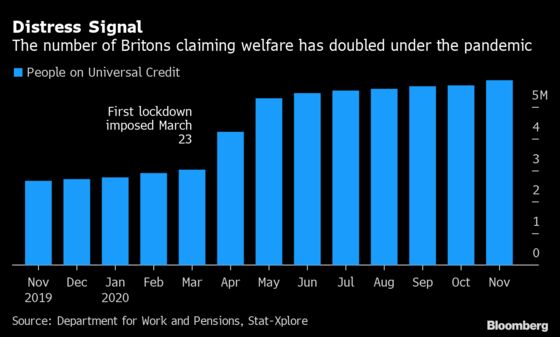

While the rollout of Universal Credit became a lightning rod for attacks on the Conservative government over its spending cuts over the past decade, it has held up well during the crisis. It coped with a surge in demand in the early days of the crisis that saw claims run at more than 10 times the average level.

But problems remain. Even with the uplift, families unable to find work will on average receive 1,600 pounds less per year in social security support than they would have done in 2011, according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Keeping the boost for Universal Credit and other legacy benefits will cost more than 8 billion pounds a year, the foundation estimates. While that’s a fraction of the total spending on the crisis, extending the policy will hamper Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak ’s longer-term goal of returning the virus-ravaged public finances to a more sustainable footing.

The safety net of Universal Credit will become more important if predictions for a jump in unemployment, already at the highest since 2016, transpire later this year.

“We’re hopeful that it will continue from April, but we’re worried it’s going to be a really last-minute decision,” McDonald said. “The people that it affects are the people who are going to need the certainty the most.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.