No Candidate Is Telling German Voters What Their Plans Will Cost

German Economic Renewal Depends on Hard Choices Obscured by Vote

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the New Economy Daily newsletter, follow us @economics and subscribe to our podcast.

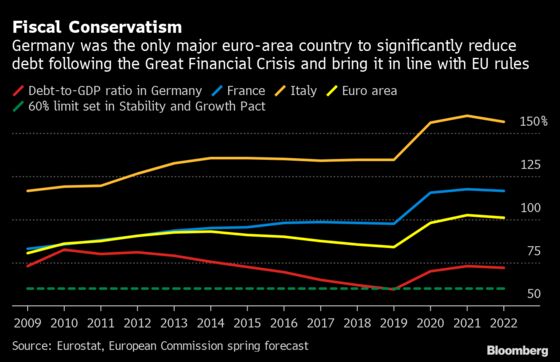

German voters haven’t heard much from Angela Merkel’s potential successors about how they will reconcile their spending ambitions for Europe’s biggest economy with the budget prudence that defined her chancellorship.

Silenced by the electoral liability of such talk in a country that venerates fiscal reticence, politicians including Social Democrat candidate Olaf Scholz, whose party is leading opinion polls over the bloc she represents, are putting off a discussion on the need to finance massive investments to retool for a digital, climate-friendly future.

Instead, the left-of-center Social Democrats and Merkel’s conservatives are both publicly campaigning on platforms that insist a constitutionally enshrined limit on adding too much debt, suspended for the pandemic, should be eventually reinstated. Quietly though, leading officials from the two major parties are exploring ways to loosen or sidestep such rules in the wake of the Sept. 26 election.

How far they’re willing to confront that sacred cow, to allow for borrowing to finance the transformation of an economy still largely engineered around the miracle of its 20th century postwar resurrection, will determine Germany’s future growth potential -- and thereby its importance, economically and politically, on the global stage.

“It’s wishful thinking to expect a structural shift requiring large investments while consolidating the budget and sticking to the debt brake,” said Carsten Brzeski, an economist at ING in Frankfurt. “If politicians want to be honest with voters, they’ll need to put a price tag on the transformation and decide whether their strict fiscal rules are still appropriate.”

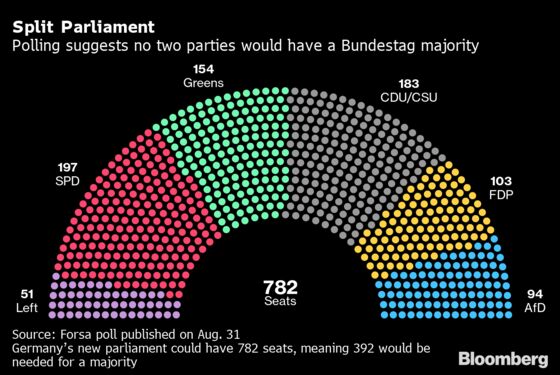

Only after the September election, when coalition talks kick off in Berlin, will the political class begin to answer such questions. With Merkel set to leave the stage, such negotiations may be closely scrutinized by fellow euro members wondering how the outcome will set the tone for engagement after decades of preaching budget discipline.

Current fiscal plans envisage a sharp tightening in 2023, with the deficit falling from 100 billion euros ($119 billion) to 5 billion euros within just one year. They also foresee consolidation of pandemic-incurred debt within two decades -- a goal that would mean repaying about 24 billion euros in bonds every year.

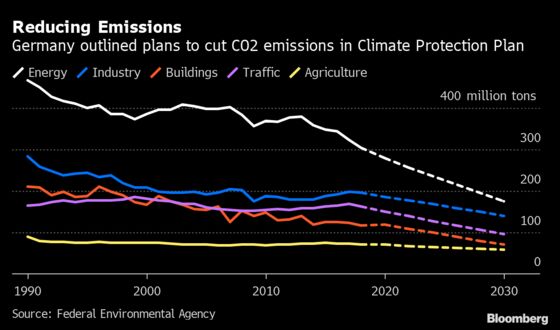

But investment needs already total 220 billion euros through 2030, estimates by the German Institute for Economic Research, or DIW, show. The cost to the economy in that timeframe of modernizing toward a 2045 goal for net zero carbon emissions could be as much as 460 billion euros, according to think tank Dezernat Zukunft-Institute for Macrofinance.

With that in mind, there is some consensus among major parties that higher investment is needed. So existing budget projections will probably soon change.

Scholz, the current finance minister, is campaigning on a conservative fiscal agenda that includes seeking to reinstate the debt brake, a stance likely to draw in votes but one at odds with his own party.

His grass roots are open to big spending initiatives, and the Social Democrats’ leftist leaders have even proposed a 500 billion-euro investment plan financed by borrowing. The divisions within the party on fiscal matters risk proving a major distraction to Scholz if he does replace Merkel, as polls currently suggest he will.

Her conservative ruling bloc, led by Armin Laschet, seems thriftier. Placed second in polls, the CDU wants to restore balanced budgets “as soon as possible” and bring debt levels below 60% of output. But Laschet has also floated a special fund to finance investments, an idea his campaign program doesn’t mention.

Annalena Baerbock’s Green Party, a likely coalition partner polling third, wants an overhaul of the debt law to create a Golden Rule exempting investments, a move requiring an almost unachievable 2/3 Bundestag majority. It also proposes a special-purpose vehicle to finance projects worth 50 billion euros a year.

One roadblock to spending big could be the liberal Free Democratic Party under Christian Lindner, a possible kingmaker in coalition talks. He wants a “turbo repayment” of debt and argues for a strict budget policy.

“The moment of truth in redesigning fiscal rules will come,” said Philippa Sigl-Gloeckner, a former finance ministry official who leads Dezernat Zukunft. “Hopefully, whatever happens won’t be small -- because that won’t be enough.”

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“Elections in September will offer more insight into the prospects for public investment in a world without Chancellor Angela Merkel. But there’s a general consensus of more infrastructure spending, which should provide some support to capital contributions to growth in the coming years.”

--Maeva Cousin, senior euro-area economist. Read more here

Should the conservatives win the election and lead the next government, getting them to spend big won’t be easy, not least in a country with a disastrous history of delayed and bloated public projects including Berlin’s new airport.

“The government isn’t the best entrepreneur,” said Volker Wieland, an economics professor at Frankfurt University and a member of the government’s council of economic advisers. “The debt brake is good and I see no need to change it.”

While such views are rife toward the conservative side of the spectrum, there are signs of a shift. Markus Soeder, the popular leader of Merkel’s Bavarian coalition partner and a former fiscal hawk, declared after devastating floods in July that Germany must reconcile the need for climate protection with its budget rules.

For now, Morgan Stanley economists predict the debt brake limiting new borrowing to 0.35% of output -- currently some 12 billion euros a year -- will remain suspended one year longer than its planned reinstatement in 2023, perhaps with some looser terms.

Sigl-Gloeckner reckons one tweak that could transform the measure would be a reinterpretation of part of the rule that allows spending when the economy is lagging, a shift that wouldn’t require constitutional change.

“You’ll get a better idea where the limits are when you think about the potential of an economy and what it can actually achieve,” she said. “We need more flexible instruments that focus less on amounts -- and more on the goals.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.