How Tear Gas Became the New Norm on the Streets of Hong Kong

Any deaths would add more fuel to the biggest challenge to Beijing’s rule, further damaging the city’s image among investors.

(Bloomberg) -- As protesters blocked roads in Hong Kong’s central business district this week, something unusual happened: Tear gas canisters began raining down from the sky.

It was unclear where they were coming from, but police officers wearing gas masks were seen on the roof of a nearby building. A video of the incident appeared to show aluminum canisters trailing smoke as they fell at least 10 stories, landing in the middle of hundreds of demonstrators.

The incident marked one of the more dangerous uses of tear gas in nine weeks of rallies that have rocked the financial hub, and underscored the growing risks of a fatality as both police and protesters become more aggressive. The more that police fire tear gas, the better protesters become at countering it -- leading authorities to deploy even harsher measures.

Any deaths would add more fuel to the biggest challenge to Beijing’s rule since it took control in 1997, further damaging the city’s image among investors. China has encouraged the police to use greater force to subdue protesters rather than meet their demands, which include an investigation into police violence and the resignation of Chief Executive Carrie Lam.

“Non-lethal weapons are non-lethal only if they are appropriately used,” said Lawrence Ka-ki Ho, an assistant professor at the Education University of Hong Kong who is an expert in policing and public order management. “If you fear more, you may uncontrollably use more force.”

Without Warning

Police in recent weeks have already used far more tear gas than at any point in Hong Kong’s history, and it’s affecting more than just protesters. It’s been used sometimes without warning in shopping districts, central neighborhoods packed with residential high-rises and suburbs popular with young families. Journalists covering the demonstrations have reported skin rashes and other health issues.

For the Beijing-backed local government, tear gas is an effective way to quell protesters who have become increasingly violent, brandishing iron poles, surrounding police stations and lobbing bricks and Molotov cocktails in clashes with police. Lam’s administration has defended officers from opposition’s allegations of excessive force and abuse, arguing that police are using reasonable means to deal with extreme circumstances.

“All over the world, police always use tear smoke as a riot-control agent,” pro-establishment lawmaker Regina Ip told Bloomberg News on Tuesday. “It’s actually a better instrument than using police batons or rubber bullets.”

The use of smoke looks dramatic but is a relatively safer type of crowd control that prevents injuries that may come via other methods, according to Steve Vickers, chief executive officer of risk consultancy Steve Vickers and Associates and a former head of the Royal Hong Kong Police Criminal Intelligence Bureau.

“The escalation of force is smoke before batons,” Vickers said. “It looks terrible on TV. You get big flashes and bangs, and it looks gruesome. But it’s the first level of force, and the next is batons and bean bags and rubber bullets.”

Protesters are becoming more adept at developing tactics to neutralize the effects of tear gas, from wearing gas masks to clamping traffic cones and cooking pots over fizzing canisters. They have even affixed gas masks on elderly passersby. A representative from Hings Group of Companies, which sells gas masks and other items in Hong Kong, says it has run out over the last two months amid a surge in demand.

“I’m not afraid of dying,” said a 25-year-old electrician with the surname Poon who declined to give his full name as he marched last week into the streets toward the central government liaison office, where riot cops shot several volleys of tear gas. “If I get injured or killed, it’s the responsibility of the police.”

‘Serious Injury or Death’

The police response to the demonstrations had drawn international condemnation even before the barrage of tear gas. Then-U.K. foreign secretary Jeremy Hunt announced a ban on export licenses for crowd control equipment in June, pending a “robust, independent investigation into the violent scenes that we saw.”

U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi this week reiterated a call for the Trump administration to “suspend future sales of munitions and crowd control equipment to the Hong Kong police force,” a statement that drew a harsh rebuke from China. Senator Ted Cruz issued a similar statement.

At least some of the tear gas used comes from Pennsylvania-based NonLethal Technologies, which has warned that firing canisters directly at individuals risks “serious injury or death.”

Hong Kong’s Secretary for Security John Lee has also defended the force, saying police have ensured a safe distance from protesters when firing the gas -- and that it was deployed in addition to other tactics, including arrests.

“I believe these considerations are in line with that of other police forces internationally,” he said Tuesday.

Over the past couple of months, the weekly use of tear gas -- which is banned in warfare along with other chemical and biological weapons, but whose use remains legal as a crowd-control measure -- stands out in Hong Kong’s modern history, where its use has been rare to non-existent.

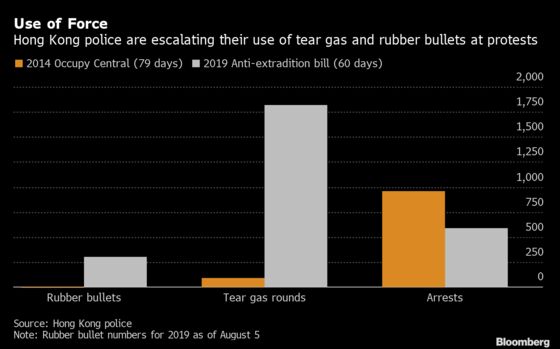

During the pro-democracy Occupy movement that shut down parts of the city’s business district in 2014, the surprise use of tear gas against a local crowd for what was arguably the first time brought hundreds of thousands of people into the streets in outrage. In total, police launched 87 rounds during 79 days of unrest.

By contrast, police have fired more than 1,820 rounds since June 9, and lobbed more than 150 canisters on June 12 alone, the day protesters tried to storm Hong Kong’s Legislative Council building in an escalation of violence.

“No matter what legal justification they can provide, the use of non-lethal weapons still may need to be restrained,” said Ho, the policing scholar. “It’s not just about dispersing the crowd, but they could actually harm or destroy the police-citizen relationship.”

--With assistance from Natalie Lung.

To contact the reporters on this story: Iain Marlow in Hong Kong at imarlow1@bloomberg.net;Sheryl Tian Tong Lee in Hong Kong at slee1905@bloomberg.net;Shawna Kwan in Hong Kong at wkwan35@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Brendan Scott at bscott66@bloomberg.net, ;Daniel Ten Kate at dtenkate@bloomberg.net, Karen Leigh

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.