Europe’s Cross-Border Commuters Risk a Home-Office Tax Trap

Europe’s Cross-Border Commuters Risk a Home-Office Tax Trap

(Bloomberg) -- There’s a tax trap looming for Europe’s cross-border commuters and the companies that depend on them, if working from home becomes permanent following the pandemic.

After coronavirus lockdowns rolled across Europe, tele-commuting has become a way of life, and many want it to continue. But more than 1 million people who live in one country and work in another, and their employers, face a potentially expensive headache.

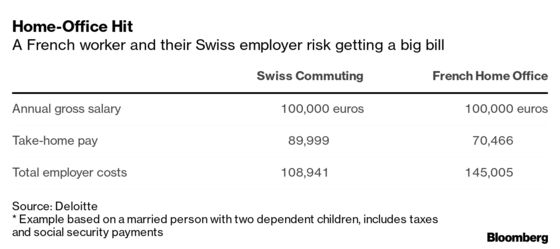

The outcome threatens to sap an employee’s wages by thousands of euros a year and increase a company’s personnel costs by tens of thousands because of a dizzying array of rules on taxes and social insurance that could create liabilities in another country.

Take the example of an IT expert living in France and working just across the border in Geneva. The law says they pay tax in the Swiss city, as long as they don’t also spend time working in France. If they do, they and their employer risk getting hit with a bill from different tax and social insurance regimes.

Accounting firm Ernst & Young labeled the combination of teleworking and cross-border employment a “perfect storm.”

Tax authorities will “be looking to see if companies roll out these working-from-home policies and then they’ll be tracking these people,” said Elsa Gardel, an EY tax specialist.

London bankers who waited out Britain’s lockdown abroad were told to return for fear of complicating matters with the U.K. Treasury for them and their employers.

So far, their peers in Frankfurt, Zurich and Milan aren’t immediately at risk of the same fate because Germany and Italy both have deals with Switzerland to nullify any tax impact from working abroad during the pandemic. They roll over automatically each month.

But France’s pacts with Luxembourg and Switzerland -- two hubs for international businesses -- run only until the end of this year, after being extended for four months last week.

Days worked at home because of Covid will be “considered as days worked in the state where they usually exercise their activity” and so taxed there, the French Finance Ministry said in their statement announcing the extension with Switzerland. It didn’t comment on plans for next year.

Under normal circumstances, European employees are allowed to perform less than a quarter of their work in another country -- basically not more than one day a week -- without becoming liable for social insurance contributions there. So if those rules become the norm again, the convenience of working near kids and without the daily grind of a commute is basically over.

That’s an issue for companies like drugmaker Novartis AG, whose base in Basel abuts both Germany and France.

“The choice of living in another country than the one where you work has positive and negative effects -- limiting flexibility regarding where you work is one of the negative consequences,” Steven Baert, Novartis’s human resources chief, said to Bloomberg.

‘Pay in France’

While company executives worry about the costs, the temptation to end pandemic tax pacts may become too great for authorities to resist as economies struggle to rebound and state coffers dwindle. French towns on Geneva’s doorstep -- popular with cross-border commuters, or frontaliers -- see the revenue potential.

“If they work in France, they pay in France,” said Hubert Bertrand, mayor of St. Genis-Pouilly, where two-thirds of the workforce is employed in Switzerland.

Geneva banks have long discouraged staff from living across the border, though due to concerns of a different sort: They worry that commuters could expose sensitive data to French tax authorities.

Accountants recommend companies design flexible work programs so that they don’t run afoul of the law, which can be extremely complex.

If the IT worker who lives in France has their office moved to the nearby Swiss city of Lausanne, then they’ll have to pay tax and social security in France, not Switzerland. There are also different rates for social-welfare contributions in France that can vary from industry to industry, according to EY.

Things get even messier if an employee gets promoted to an executive role and signs a big-figure contract while at home in France. That raises the possibility of their domicile being deemed what in accountant lingo is known as a “permanent establishment,” which essentially means her Swiss employer could be liable for corporate tax in France as well.

“Even before the pandemic, many companies that were putting into place flexible work schedules were looking into ‘well, do we need to have specific guidelines for our cross-border commuters’ to avoid additional unforeseen costs,” said David Wigersma, Lausanne-based partner at Deloitte SA. “The pandemic has fast-forwarded those discussions.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.