Russian Information Attacks Keep Hitting the EU’s Weak Spots

Europe Is Still Wide Open to Russian Information-Warfare Attacks

(Bloomberg) -- Since news first broke that Russian opposition leader Alexey Navalny had been poisoned with a nerve agent, some of the most popular coverage in Germany has come from Kremlin-funded outlets questioning Berlin’s efforts to blame Moscow for the attack.

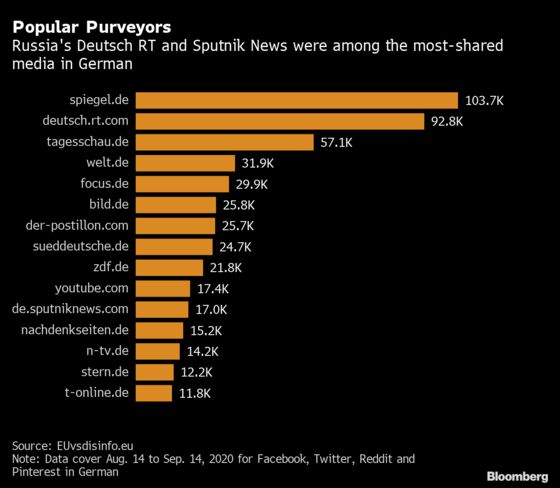

RT Deutsch’s stories denouncing the accusations as shrill and hypocritical ranked among the top 10 most shared sources on German-language social media on the subject, registering more engagement than official government statements or coverage in mainstream outlets like Welt, Bild and broadcaster ZDF, according to analysis by the European Union covering the period since the August attack.

The popular Kremlin-backed posts were just a part of a flood of stories from Russian state media across Europe that sought to cast doubt on the official German account, pushing unsubstantiated alternatives ranging from allegations Navalny’s poisoning was a western intelligence plot to claims he did it to himself. Echoing Russian officials’ statements, the torrent was picked up by some German politicians, as well.

More than five years after Europe began trying to combat Russian disinformation in earnest, the Kremlin’s campaigns are still hitting their targets. Alongside overt operations that take advantage of an information landscape that makes people distrustful and willing to buy into conspiracy theories, Moscow’s outlets have steadily adapted their tactics to evade efforts to combat them, often using local media and writers to avoid detection and reach receptive audiences. The EU’s focus on exposing Russian disinformation hasn’t succeeded in substantially limiting its reach.

Kremlin ‘Undeterred’

“The Kremlin remains largely undeterred in using disinformation as a political weapon,” said Monika Richter, a senior director at Counter Action and former EU official at the East Stratcom Task Force. “The EU still predominantly tackles disinformation as a tech governance challenge -- but it is also a geopolitical security threat.”

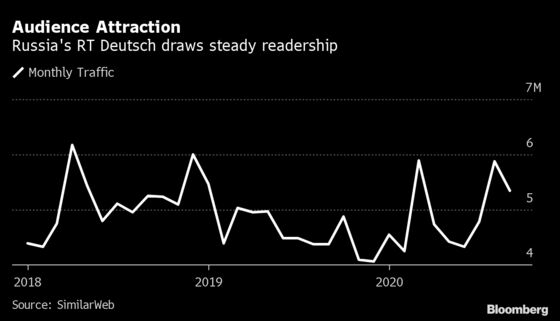

German counterintelligence singled out RT Deutsch and the state-backed Sputnik in a report published this year, saying that both play a “central role” in Russian disinformation operations and influence campaigning. But both continue to operate freely in Germany. RT Deutsch has more than 520,000 followers on Facebook and 437,000 subscribers on YouTube. They are especially popular among immigrants from the former Soviet Union and supporters of far-right and left parties.

“The main appeal is they pretend to present the truth that other media hide,” said Susanne Spahn, an independent researcher on the issue. “This strategy to present themselves as independent and alternative is popular among special groups in Germany who have lost trust in mainstream media.”

The Kremlin’s counter-narratives in the Navalny case have been echoed by German politicians. Sevim Dagdelen, a lawmaker with the anti-capitalist Left party who sits on the foreign affairs committee on the Bundestag, said on a widely watched talk show that it wasn’t at all clear whether the Novichok came from Russia since western intelligence agencies also had the agent.

Pushed by Sputnik in Italy and Poland, as well, that account also showed up in local media in Hungary and the Czech Republic, where several websites citing another Russian source claimed the whole case was a U.S. operation.

Political Fringes

To be sure, the Russian narratives rarely break out of the political fringes. In Germany, support for extremist parties has dropped during the coronavirus pandemic while backing for the government has strengthened. The EU study found that RT and Sputnik content about Navalny was far less successful when it came to English-language social media.

Still, Russian disinformation operations in recent years have expanded and become better, more targeted and sophisticated, which has in turn made it harder to trace.

“There is an increased focus in finding domestic local actors that will spread and amplify disinformation,” said Jakub Kalensky, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab and former head of the EU team countering Russian efforts. “The EU is moving slower than the information aggressors.”

In Finland and Lithuania, government programs in schools to teach students how to identify disinformation are credited with helping increase resilience to Russian efforts. The U.S. has forced Kremlin-backed media to register as ‘foreign agents,’ an approach that European officials have so far avoided on civil-liberties grounds.

Russian efforts have been detected beyond issues directly affecting Moscow. Two French websites with ties to a news agency previously linked to Russian military intelligence were found this summer to be spreading disinformation about Covid-19. A fake story about failed vaccine trials in Ukraine originally published on the website of the self-proclaimed Lugansk People’s Republic was picked up by several Russian-language media and fringe conspiracy outlets earlier this year.

Fake Personas

Russian-controlled outlets have used fake personas, local websites masquerading as independent outlets andforged documents to push claims that Covid-19 was manufactured in North Atlantic Treaty Organization country labs, according to analysis gathered by the military alliance.

The EU acknowledges that some member states could be doing more to combat and prevent disinformation from spreading in their own countries.

“Disinformation is usually sophisticated in the way that it is tailor-made for a specific market in the local language and in the local context of its history, relations with Russia, ethnic composition, political situation, presence of far right or far left political parties and local actors willing to be part of the disinformation activities,” said spokesman Peter Stano. “There is a big role for the member state to fight disinformation.”

But governments struggle to keep up. “The toolbox of conventional government communications is insufficient to expose the covert strand of the Kremlin’s ongoing disinformation campaign,” said Stratcom’s Richter.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.