Ending Politics as Usual, Colombian President Falls on His Face

Ending Politics as Usual, Colombian President Falls on His Face

(Bloomberg) -- When Ivan Duque ran for president of Colombia last year, opponents said he’d be little more than a puppet of his mentor Alvaro Uribe, the rightist ex-president who launched his career.

While acknowledging his debt to Uribe, Duque insisted he was his own man. He’d lead a cabinet of capable young ministers rather than party hacks, and put an end to pork-barrel politics. Many were skeptical. But in the five months since taking office, Duque has been true to his word.

It has derailed his presidency.

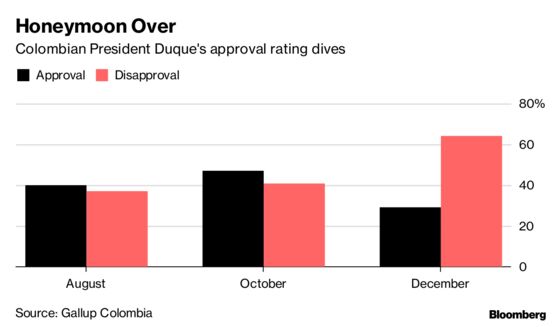

His plan to raise taxes was torpedoed by his own party. The main stock index has fallen 19 percent in dollar terms, more than any other major market in the Americas, while Duque’s approval rating has plunged even faster. Many of his allies are demoralized; the leftist opposition smells blood.

“Wonky Centrist”

“He’s trying to govern as a wonky centrist but it’s a rough path in a country as polarized as Colombia,” said Brian Winter, editor-in-chief of Americas Quarterly, who’s a friend of Duque and helped Uribe write his autobiography. “In his circle there is a sense that he needs to push the reset button and find a rallying cry that will unite at least half the country.”

Duque hasn’t been able to deploy the dozens of lawmakers of his own Democratic Center party as an effective bloc to push the government’s agenda, nor has he built a ruling alliance of the type that the last government had.

He’s forsworn the age-old practice of buying lawmakers’ support with “jam,” or political favors, but lacks the tools to govern without it. With no heavyweight political operators in the cabinet, he has struggled to communicate with lawmakers and failed to connect directly with the public.

The challenges faced by Duque, a 42-year-old lawyer, would be colossal even for a political genius. The country is bearing the brunt of one of the world’s biggest migration crises, with more than 1.2 million Venezuelans now living in Colombia, and thousands more crossing the border in desperation each day. Cocaine production has more than tripled over the last five years, bringing violent chaos to the regions where it is produced and undermining a historic peace process with Marxist rebels, many of whom have taken up arms again.

Meanwhile, public finances have been hit by a 22 percent drop in the price of oil, the nation’s biggest export, since Duque took office. The price of coffee, on which half a million Colombian families depend, recently touched a 12-year low.

Neither the president’s office nor the finance ministry replied to questions seeking comment.

The Democratic Center party, whose logo is a silhouette of Uribe with his hand on his heart, has sometimes actively opposed the government and sometimes remained on the sidelines, leaving the government on its own, according to Sandra Borda, dean of the Social Sciences Department at Bogota’s Jorge Tadeo Lozano University.

Since the government has tried to end the old horse-trading way of politics, it needs to be better organized at defending its initiatives and coordinating with lawmakers, said Christian Garces, a congressman from Duque’s party, in a phone interview.

Duque’s experience could serve as a cautionary tale for his neighbor, Brazil’s new president, Jair Bolsonaro, who also pledged to overhaul relations with congress, ending the practice of “take there, give back here,” the Brazilian expression for jam.

The Duque government’s failure to communicate effectively either with congress or the public has compounded its troubles. When the previous government passed an unpopular VAT increase in 2016, the finance minister at the time, Mauricio Cardenas, met with political leaders and flew all over the country giving TV and radio interviews to explain why it was necessary.

Honeymoon Over

Duque’s finance minister, Alberto Carrasquilla, gave a single press conference to present his plan in which he proposed to tax sacred family staples such as rice and beans. After that, he was barely heard from and left a deputy minister in his early thirties to defend the proposal in the media. Duque’s honeymoon ended around that time.

When Duque was campaigning, he was sometimes called the Latin American Macron, a reference to France’s young technocratic leader Emmanuel Macron. Both governments have since been plagued by communication blunders and falling popularity.

It was Uribe himself who led the opposition to Duque’s tax proposal, forcing the finance ministry to rethink it entirely. Some felt that the government could have avoided the crisis simply by talking with its own allies in congress.

“We could never understand this stubbornness or this attitude of persisting with this proposal,” said Jose Obdulio Gaviria, a Democratic Center senator, in an interview in Bogota. “We knew in advance, because we’re in contact with the other parties in congress, that there was no possibility that the minister would achieve this proposal of extending VAT.”

Little Coordination

There was little in the way of meetings or coordination with Democratic Center lawmakers to discuss the plans, Garces said. He added that the government and congress have since made progress in working together.

The tax bill barely resembled the original by the time it got through congress, and it raised just half the revenue. An attempt to reform the electoral system suffered a similar fate, while a reform of the justice system failed to pass.

Some of Duque’s supporters want him to be more like U.S. President Donald Trump, or Brazil’s Bolsonaro, but this doesn’t gibe with his moderate, intellectual personality, said Winter.

“It’s another case that proves that if you are not governing from the energized extreme, you are going to feel pretty lonely,” Winter said.

--With assistance from Oscar Medina.

To contact the reporter on this story: Matthew Bristow in Bogota at mbristow5@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Vivianne Rodrigues at vrodrigues3@bloomberg.net, Ethan Bronner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.