Macron’s Bravado Belies the Far-Right’s Advance in France

Macron’s Bravado Belies the Far-Right’s Advance in France

(Bloomberg) -- Two days after Angela Merkel apologized to Germans for making a mistake in how she handled the coronavirus crisis, Emmanuel Macron was not sorry.

That is in spite of France seeing infections spiral out of control after the president overruled the advice of his own health minister to keep the economy open. A sclerotic immunization program has been muddled by his public flip-flopping over the safety of the AstraZenca vaccine. And doctors are worrying about a shortage of intensive care beds.

“We were right,” he said Thursday night of his delayed lockdown strategy. “I have no mea culpa, no remorse, no sense of failure.”

A year from now French voters will cast their verdict on his performance amid mounting evidence that the self-confidence on display is a turn-off. By contrast, far-right leader Marine Le Pen has worked hard to broaden her appeal and is striking a humble tone. She’s a lawyer, not a virologist, she said during a two-hour prime time interview this month in a swipe at a president whose advisers present him as a science expert.

The rivals are practically neck-and-neck in the polls.

Historian Jean Garrigues says it’s highly unusual for French presidents to apologize because they’re meant to appear infallible, but people were “perhaps ready” to hear Macron say he was sorry for the hiccups with the government’s strategy. That could have helped soften the image of a man perceived as “distant, removed from the people, arrogant,” Garrigues added.

The scale of Macron’s task is not helped by the fact that France is one of the most vaccine-skeptical countries in the world, and his own government warned that a vaccination campaign wouldn’t be easy. Indeed about 10% of the population has been inoculated at least once, a fraction of the pace in the post-Brexit U.K. where more than half of all adults have received one jab.

In Germany, Merkel said she’s willing to overpower states if it means getting the pandemic under control.

The French government didn’t do itself any favors by changing its mind three times on how to use Astra, the vaccine it’s counting on. Macron went from saying in early January the inoculation was “quasi-ineffective” in people over the age of 65, to suspending it amid a health scare before clearing it for the middle-aged and beyond earlier this month.

A recent Elabe poll for BFM TV found that more than half the French don’t trust the shot. The country is now in its third wave, and Germany just designated it a high risk area, because the incidence rate has surged to over 300 infections per 100,000 residents.

One French minister, speaking on the condition of anonymity, expressed confidence the delays in the vaccine rollout will be a distant memory by the middle of the year, when Macron has vowed all adults willing to get vaccinated will be inoculated. And a ministerial adviser said voters will remember the president’s successes, not “the diesel-car-like start” of the vaccination drive.

Those successes include Macron having persuaded fiscally conservative Germany to take on eurozone debt together, as lockdowns imposed to curb the pandemic choked off economies across the EU. French hospitals, while under pressure, are holding up. Schools are still open. Deaths per capita are lower than in the U.K., the U.S. and many other comparable countries.

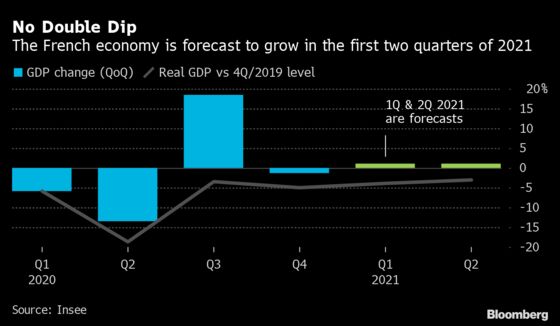

And the euro area’s second-largest economy has resisted better than initially expected. Most French employees have been supported by the state thanks to a generous work furlough scheme, and the 2021 growth forecast of 6% is predicted to hold.

In explaining his decision not to lockdown the country again in January, Macron has insisted it was a last resort given the human and financial cost for the economy. So far he’s opted instead for a localized approach (one the U.K. tried and then abandoned last year), that included further restrictions in Paris.

While that tack pleased some voters, it also led to unease — even among officials within Macron’s party. Le Pen, sensed an opening.

She has compared the government’s strategy with the body of a dead dog drifting in water currents without purpose and lashed out at Macron for not closing borders with European Union countries early in the crisis. Her advisers say France could have immunized its people faster if it had handled vaccine purchases itself, instead of the bloc.

That’s basically reproaching him for not taking a more British approach. The U.K. has redeemed itself somewhat in the public eye with the speed that it got jabs in arms. Boris Johnson almost died of Covid and it changed his perspective on a disease he had initially taken lightly. For Macron, who also got it, it was not a life-threatening experience. His government remains very critical of the U.K.

Members of Le Pen’s National Rally party attacked Macron after Thursday’s press conference, accusing him of arrogance, with its deputy Jordan Bardella, telling BFM tv that the president was “infantilizing” voters.

In some ways, Macron himself is to blame for her comeback.

Over the past year, amid an uptick in jihadist violence, Macron lurched from the center further to the right, with tough talk on crime, illegal immigration and an attempt to create a special brand of secular French Islam to try and pull the rug out from under Le Pen. He’s even appointed a hard-line interior minister who’s against displays of multiculturalism. Hearing both sides on the sensitive issue of Islamists, there is not much separating them.

It’s a massive departure from Macron’s 2017 electoral campaign when he cast himself as a defender of liberalism, and was hailed a hero by a western world reeling from Brexit and a Donald Trump White House.

Observers say the president anticipates he’ll score an easy victory over Le Pen in April 2022, because progressive voters will ultimately rally behind him just like they did last time. But there is a risk they could just stay home instead and there’s plenty of anger elsewhere, too.

Macron arrived in the Elysee as a 39-year-old former investment banker with a clean slate having just built a party from scratch, and an unapologetic belief in his own luck that seduced his voters. Since then he’s been weakened by strikes, protests and allegations of police violence — as well as his handling of the pandemic.

As it began, Macron sought to appear like a war-time leader. Often during times like these, people cling to the incumbent. A recent Ifop poll showed Macron’s popularity at 37%, higher than his most recent predecessors, Socialist Francois Hollande and right-wing Nicolas Sarkozy, at the same point in their terms. Both only served one mandate.

Recently, though, the president acknowledged the virus was the real “time-master,” not him. And he began passing the buck to his prime minister, which the constitution allows him to do, according to Garrigues, the historian. That shift didn’t prevent the government from imposing measures to curb Covid-19 so complicated that even ministers didn’t fully understand them at the start.

The jury is out on what kind of toll the pandemic will take on his presidential fortunes. Cecile Alduy, a Stanford-based language expert who is studying the language of politicians, is critical of Macron’s dialectic, his attempts to reconcile all points of views and provocative outbursts deemed patronizing to the lower social classes. Whether he likes it or not, Macron’s fate is now linked to the virus.

Or as Alduy puts it, he’s now “the President of Covid.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.