Dying Father’s Dream Drives Abe to Seek Peace on Putin’s Terms

Shintaro Abe urged Russia to return the four windswept Pacific islands the Red Army seized in 1945.

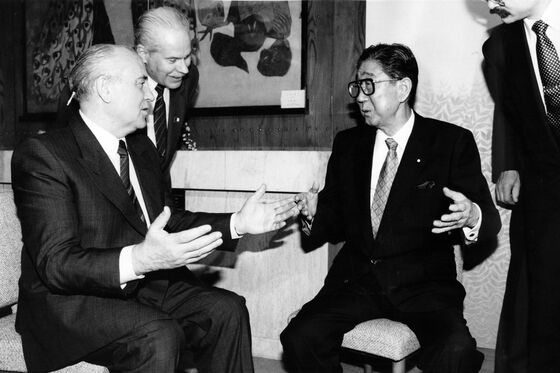

(Bloomberg) -- Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s father lay dying when an old acquaintance, embattled Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, arrived in Tokyo.

It was 1991 and the cancer-stricken Shintaro Abe, a former foreign minister, mustered the strength for what turned out to be one last pitch for peace. Escorted by Shinzo to a meeting with Gorbachev in a wheelchair, Shintaro again urged the recently crowned Nobel Laureate to return the four windswept Pacific islands the Red Army seized in 1945, triggering a bitter dispute that continues to prevent Russia and Japan from formally ending World War II.

Now the younger Abe is racing against the political clock to fulfill the dream of his dad, who died weeks later. With less than three years to go before he must cede power, Abe is bucking seven decades of Japanese policy—and public opinion—in the dogged pursuit of a peace treaty with Vladimir Putin that looks set to return only two of the islands, officials from both sides say.

Abe and Putin, who’ve met 24 times since 2012, are closer to a final agreement than ever, with some officials and analysts predicting a deal in a matter of months. The Japanese premier, who is tentatively scheduled to visit Moscow in January, called their most recent encounter, in November, a breakthrough.

“There’s been no change in Russia’s position. It’s Japan’s that’s changed,” said James Brown, an expert on Russo-Japanese ties at Temple University in Tokyo. “Abe is determined to complete his father’s life work and burnish his own legacy as the Japanese leader who finally resolved one of the lingering diplomatic issues of the post-war era.”

Forging closer relations with Russia would also give Japan a new lever of influence over China and North Korea, two nuclear-armed rivals that Putin has assiduously courted. For the Kremlin, deeper ties to America’s richest ally would help alleviate Russia’s isolation from the West, particularly if the two islands likely to be returned will be exempt from Japan’s security pact with the U.S., as Putin is demanding.

Putin said Thursday that Russia can't make any ``major decisions'' on the islands issue without resolving concerns over Japan's security arrangement with the U.S, though it wants to reach a deal.

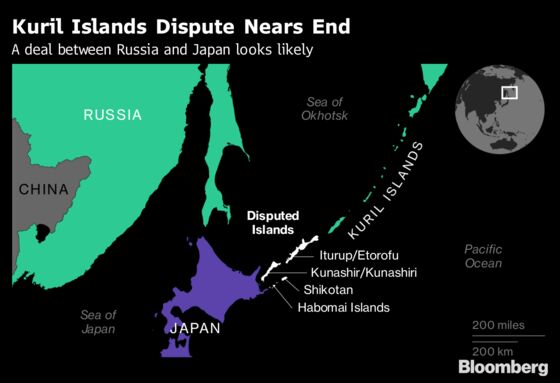

In Singapore last month, Abe and Putin agreed to accelerate talks based on a 1956 Soviet-Japanese declaration, which stipulated the return of the smallest two of the four islands, a chain known as the Southern Kurils in Russian and the Northern Territories in Japanese. (The Soviets reneged on that agreement when Abe’s maternal grandfather, Nobusuke Kishi, was prime minister in 1960, citing Japan’s military accord with the U.S.)

The shift to the 1956 position was a major reversal for Japan, sparking a domestic backlash against Abe since it would leave Russia the de facto owner of the two bigger islands. A former deputy premier and foreign minister, Katsuya Okada, called Abe’s offer a “major and unnecessary concession that weakens Japan’s position.”

Putin, too, is risking his public approval rating, which has steadily ebbed since cresting after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea, most recently over an increase in the pension age. A small faction of Communists in the State Duma this week demanded details of Putin’s talks with Abe, saying Russia’s “territorial integrity should not be the subject of any bargaining and non-public agreements.”

And with the negotiations continuing, hardliners in Russia’s military are finding subtle ways to intensify the pressure. On Monday, the Defense Ministry in Moscow angered Tokyo by announcing the construction of new barracks to enlarge its current deployment of about 3,500 troops on the two largest islands.

“There’ll be nationalists opposed to any territorial concession, but Putin, as a respected leader, can deal with this,” said Alexander Lukin, a Japan specialist at the Moscow State Institute of International Relations. “People will mostly understand that it’s worth surrendering a few outposts to achieve good relations with Japan.”

Putin and Abe, masters of very different political systems, both have firm holds on power. A poll last month showed that only 17 percent of Russians support giving back any islands to Japan, a number that history suggests will certainly rise once Putin, who enjoys quasi-czar status, starts making his case for an agreement directly to the public.

Recent Japanese surveys show a majority would accept the immediate return of two islands, though opinion is nearly unanimous that all four should be handed back eventually, complicating Abe’s efforts to rally the public behind an accord. Still, Abe’s ruling coalition has a comfortable majority in both houses of parliament, which must approve any treaty.

“This problem hasn’t moved a millimeter since the war,” said Harumi Takahashi, the governor of Japan’s northernmost Hokkaido province, which lies just off the disputed islands. “We are watching with high hopes the prime minister’s and the government’s realistic policy of proceeding with negotiations based on the 1956 declaration.”

Abe’s betting that emphasizing his emotional stake in resolving the dispute will pay off politically. In 2016, as he waited for Putin to arrive in his ancestral home of Nagato for the so-called Hot Springs summit, he visited his father’s grave. Afterward, he gave an interview to Russia’s Tass news service in which he called the Gorbachev meeting a defining moment of his life.

“I was there, and just that month my father departed our world,” Abe said. “I was able to witness his stubborn desire to solve the problem of Japanese-Soviet relations, even though it cost days of his life. That’s when I decided to embark on the path of politics and inherit the aspiration of my father.”

Alexander Panov, a former Russian deputy foreign minister and ambassador to Tokyo, said if the two countries can’t sign a peace treaty before Abe leaves office then they probably never will.

“This is a historical moment,” he said. “We can’t miss this chance.”

--With assistance from Samuel Dodge and Emi Nobuhiro.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brad Cook at bcook7@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.