Fiscal Crises Grip U.S., Europe Over Aid to Their Weakest States

Coronavirus Tests State of the Unions on Both Sides of Atlantic

(Bloomberg) -- The coronavirus crisis is thrusting governments on both sides of the Atlantic into a fiscal emergency along with the medical one, as the European Union and the U.S. grapple with how to assist their hardest-hit members without being dragged down by them.

In Europe, indebted Italy is in need, and in the U.S., it’s big states like New York and Illinois.

The geography and political systems may differ, but the problem is the same. Both economies boast central powers that want to avoid getting on the hook for the debts of the under performers. Republicans in Washington grumble about taking on Illinois’ problems, while Berlin fears Rome’s.

In the end, the “haves” will likely succumb to assisting the “have nots.” But any aid will arrive only after a heavy dose of debt-shaming and steep guardrails on future spending.

And while the U.S. boasts the common fiscal policy that Europe lacks, each can take lessons from the other about how to assist -- but not to the point of getting hurt.

“Whenever we talk about fiscal transfers, whether within countries or among countries, the politics is always difficult -- even established confederations like the United States don’t find it easy,” said Guntram Wolff, director of Brussels-based think tank Bruegel. “Certainly, the debate in Europe remains much more polite, and overall the atmosphere is still: ‘let’s try to find a solution.”’

Crunch Point

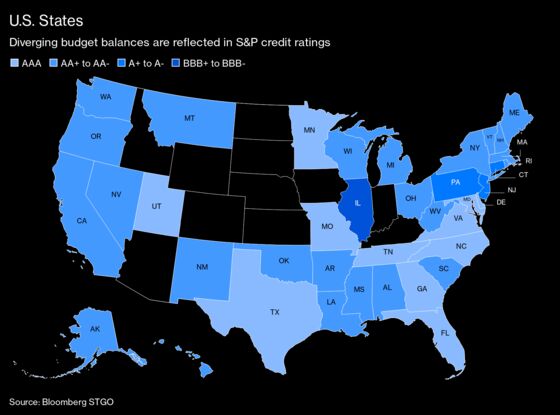

Democrats led by House Speaker Nancy Pelosi want upwards of $700 billion for states and local governments struggling with evaporating tax revenues, soaring coronavirus costs, and existing pension liabilities. The Senate’s top Republican, Mitch McConnell, retorts that the predominantly Democratic-led states hit hardest shouldn’t be bailed out for poor fiscal management, an argument being taken up by President Donald Trump, who originally sounded more supportive of state aid.

”Why should the people and taxpayers of America be bailing out poorly run states (like Illinois, as example) and cities, in all cases Democrat run and managed, when most of the other states are not looking for bailout help?” Trump tweeted Monday.

This could be gamesmanship before a negotiation, except that McConnell’s suggestion raises the stakes to imply that a particularly hard-hit U.S. state should be allowed to declare bankruptcy, something that isn’t allowed now.

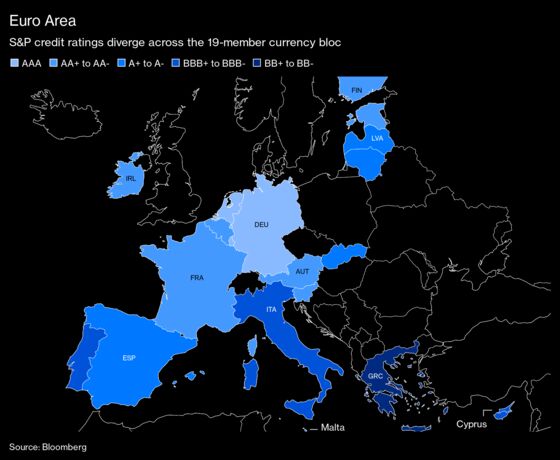

Even the euro region never let that happen with Greece, a sovereign nation in a far looser union than the U.S. But the Greek standoff did almost prompt its exit from the euro, and that memory no doubt haunts German Chancellor Angela Merkel as she confronts how to support Italy, whose own debt problems, exacerbated by the pandemic, are less self-inflicted. European leaders disagree over how to share the financial burden, beyond a short-term 540 billion-euro ($584 billion) plan agreed last Thursday.

While Italian voters are losing faith in the bloc, and northerners such as the Germans and the Dutch are reluctant to give southern neighbors a blank check, the parameters of their argument remain relatively cordial. A union formed in the ashes of a war that ended during the lifetime of some voters doesn’t yet feature many mainstream politicians telling virus-stricken Italy where to go.

For McConnell however, that language makes good politics, playing to stereotypes that faintly echo the -- more distant -- Civil War. Attacking big-spending liberals appeals to conservatives of both the fiscal and social variety, who believe Democratic leaders are as promiscuous with spending as their citizens are with morals in places like New York. Never mind that McConnell’s home state, Kentucky, relies heavily on federal largess, and has its own budget problems.

No Trust

“The broad viewpoint on the right has been that state governments have been so irresponsible for so long that Washington Republicans don’t trust them to disclose the costs that are just from the virus,” said Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute and formerly an aide to several senior Republicans including Mitt Romney.

To be sure, in America the Democratic strongholds spurned by some Republicans are key drivers of the national economy and, through their tax dollars, already subsidize smaller, more rural states. New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts and Connecticut were among the handful of states that pay far more in federal taxes than they receive in benefits, with the annual gap more than $50 billion for those states alone, according to the Rockefeller Institute of Government.

Illinois -- the state Trump singled out in his tweet -- insists that it sends more tax money to Washington than it receives. “We’d urge the president to avoid his instincts to make this a partisan issue,” said Jordan Abudayyeh, a spokesman for Governor J.B. Pritzker.

The problem for McConnell is that, taken to the extreme, his idea to let some states go under could produce a deeper recession and more uneven recovery on the other side, with vast regional variations on the economic pain that could cripple a nationwide comeback. Here, McConnell could merely look to the uneven euro-area recovery post-2011 and imagine the same thing happening in the U.S., with lingering high unemployment.

By Monday, after days of getting beaten up for his bankruptcy remarks, McConnell signaled that he expected state and local aid to get into the next package and downplayed the idea of states filing for bankruptcy. But he said he would insist on a Republican priority first: sweeping liability protections for business owners who reopen amid the pandemic.

Furloughs are already starting in cash-strapped cities in swing states at the worst possible time for McConnell’s GOP Senate, with a slim majority of just three seats. If states and local governments need to cut costs, that means raising taxes or firing workers during a recession in an election year.

“Lawmakers can talk now about sending states a message of tough love, but once states start cutting services and laying off workers, the senators and representatives are going to hear about it and they are going to rush and pass a bailout,” said Riedl.

That narrative has parallels with the fear in fiscally conservative European nations that being on the hook for Italian debt, even if it’s virus-incurred borrowing, is the thin end of an expensive wedge -- but one they may ultimately need to tolerate, at least partially.

Republicans may still need to swallow the bitter pill of a stimulus for U.S. states in need. Firstly, it’s not clear that McConnell’s suggestion of allowing insolvency can legally happen, because it effectively means a state ceding sovereignty to a bankruptcy judge.

“Our federalism form of government does not throw our partners in the democratic process under the bus,” said G. William Hoagland, a former longtime Senate Republican budget aide.

Then there’s the danger of states defaulting on bonds -- even without bankruptcy -- threatening disproportionate outcomes. Their financial strain is a result of a temporary collapse in taxes, not crippling debts. Reneging on them could lock a state out of bond markets for years, hurting growth by preventing borrowings for public works.

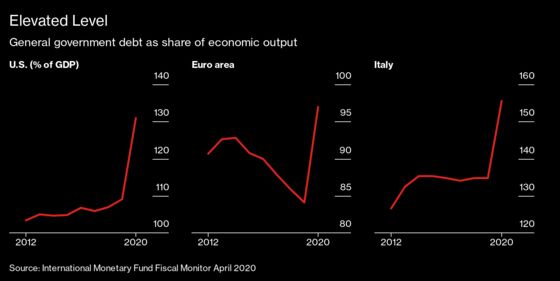

States must balance budgets each year and -- while still facing sizable pension debts -- they have roughly the same amount of bonds outstanding as they did a decade ago. Overall, the roughly $8 trillion states and local governments owe to pension funds and debt holders is less than 40% of gross domestic product.

That’s far less than Italy -- whose debt the International Monetary Fund predicts will soon reach 155% of GDP. It’s the question mark over the sustainability of those borrowings that has brought European politicians to the negotiation table, mindful that their currency could founder in the absence of a common front. What restrains them is the mixed feelings of voters in a union where the political legitimacy of sharing tax money beyond borders was never fully established when the euro was created in the 1990s.

The Europeans have yet to achieve the unity of the U.S. but they are trying harder to get along with each other. The Greek crisis taught both a recalcitrant country and its wider neighborhood that insolvency, and the prospect of parting ways, would be mutually destructive, economically and politically. That experience is informing the region’s approach to Italy, though the outcome is harder to guess at.

“If the EU does not provide the solidarity and insurance in such a crisis, parts of the EU may then question what the EU is for,” said Christian Odendahl, Berlin-based chief economist at the Centre for European Reform. “That’s why countries like Germany have been willing to debate the matter of aid -- and even transfers to the south.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.