Carney’s Not Sorry About Brexit Forecasts as Next Round Unveiled

The Bank of England got its Brexit forecasts wrong, according to lawmakers and pundits.

(Bloomberg) -- The Bank of England got its Brexit forecasts wrong, according to lawmakers and pundits. Mark Carney would beg to differ.

Members of Parliament have repeatedly declared that the BOE apologized for saying before the referendum three years ago that the U.K. might slip into recession. Brexit backers see that as evidence that warnings about future damage from the divorce from the European Union are hysterical.

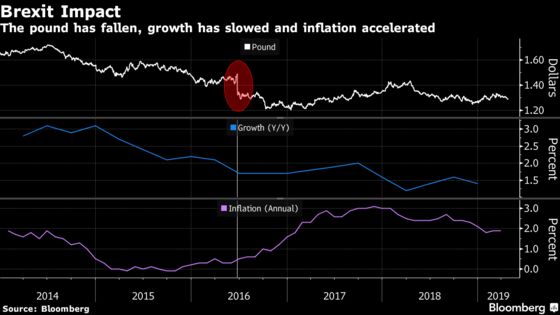

The trouble is the BOE never said sorry. Governor Carney has defended pre-referendum predictions that a vote to leave would lead to slower growth, a drop in the pound and faster inflation -- all of which transpired.

The BOE’s struggle to get its message across, and the risks to its credibility, are in focus as officials unveil their latest round of economic forecasts Thursday, the first set to be published since Britain’s planned departure from the EU on March 29 was delayed.

February’s forecasts were based on Britain leaving the EU in an orderly fashion last month. That assumption is now expected to be applied to the new deadline of Oct. 31. Economists see the BOE raising forecasts for 2019 growth and inflation.

What Carney Said in May 2016:

“Material slowdown in growth, notable increase in inflation. That’s the MPC’s judgment. It’s a judgment not based on a whim, it’s a judgment based on rigorous analysis and careful consideration.”

The BOE’s no-deal Brexit economic scenarios, published in November at the request of lawmakers, added fuel to criticism of the bank. The exercise was to illustrate how a number of outcomes could affect the bank’s ability to deliver its objectives, rather to forecast the economic impact.

But public discussion honed in on the worst case that saw GDP shrinking by 8 percent within a year, sterling dropping below parity with the dollar, inflation surging to 6.5 percent and property prices plunging almost a third.

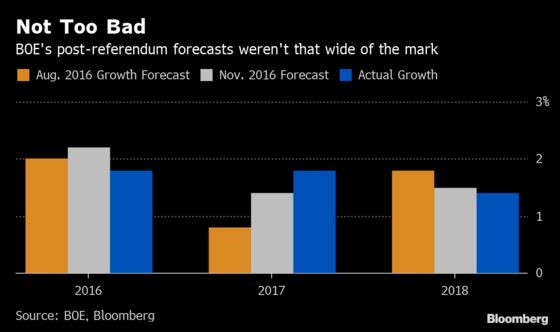

The central bank’s official forecasts haven’t been perfect either. Indeed their first post-referendum growth projections -- presented in August 2016, the same day policy makers cut interest rates -- were too strong for both that year and 2018, and too negative on 2017.

Many forecasters underestimated the strength of the global economy in 2017 and the resulting boost to Britain, which the National Institute of Economic and Social Research estimates added about 0.6 percentage point to annual growth.

Much of the criticism of Carney centers around his pre-referendum comment that the consequences of a vote to leave the EU “could possibly include a technical recession” -- something he stressed at the time was not actually in BOE forecasts.

“What we said prior to the referendum is that we thought the exchange rate would fall, perhaps sharply, inflation would go up, and growth would slow,” Carney told a House of Lords committee in January. “After the referendum, the pound fell, sharply, inflation went up, and growth slowed.”

Where the central bank’s pre-vote warnings do look less accurate is its expectations for an increase in unemployment and a pullback by consumers. Both have remained resilient, with joblessness at the lowest rate since 1975.

BOE Chief Economist Andy Haldane said in 2017 that he had expected a sharper slowdown. But his speech about the failings of forecasts, which many interpreted as a mea culpa on Brexit, was mainly about the inability to foresee the 2008 financial crisis.

The dismissal of expert views has become problematic in Britain. Any warning over the dangers of a disorderly Brexit -- from central banks, business groups or individual companies -- is frequently dismissed as scaremongering, or “Project Fear.”

Unlike the Treasury, the BOE didn’t put numbers on the economic outlook before the referendum in the event of a vote to leave. The government’s famously apocalyptic “severe shock” impact analysis saw a 6 percent drop in GDP over two years and an 800,000 increase in unemployment.

Another image problem for forecasters is that they have to rely on counterfactual projections to argue that the U.K.’s steady but uninspiring growth rate since the referendum is far lower than it might have been.

Errors are part and parcel of making predictions, and miscalculations aren’t the sole domain of those who say Brexit will be painful.

According to a list of independent forecasts published by the Treasury, the group that got its 2018 forecast most wrong was the pro-Brexit Liverpool Macro Research Group, which predicted growth of 2.6 percent. The economy actually expanded 1.4 percent that year, close to the BOE’s prediction of 1.6 percent.

To contact the reporters on this story: David Goodman in London at dgoodman28@bloomberg.net;Lucy Meakin in London at lmeakin1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Fergal O'Brien at fobrien@bloomberg.net, Brian Swint, Andrew Atkinson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.