Britain's Tortured Relationship With Europe Just Got Worse

Britain's Tortured Relationship With Europe Just Got Worse

(Bloomberg) -- There was a moment, back in the middle of March, when Europe finally tuned in to Brexit.

It wasn’t due to sudden economic concerns, but rather a morbid fascination at the spectacle unfolding in the U.K. Tales of stockpiling, emergency ferries and shortages of blood were one thing, but the paralysis in Westminster in the face of such an obvious impending crisis was incomprehensible to many Europeans. Unprompted, shop workers, baristas and taxi drivers asked what was going on. How could this happen, in Britain of all places?

German news magazine Der Spiegel captured the mood in its morning briefing for March 12, the day Theresa May put her revised deal to a parliamentary vote for the second time. “It’s painful having to watch this great European nation inflicting wounds on itself,” wrote political editor Sebastian Fischer. “It’s so unnecessary.”

May’s deal has now fallen at the third attempt, and the prime minister is running out of options to deliver on Brexit. But whatever happens now, a breach with Europe is already evident, and the troubled postwar relationship between the U.K. and its continental counterparts has taken a clear turn for the worse.

Different Notion

In truth, the U.K.’s vacillation over Europe shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone who has observed Britain’s interactions with the continent over the years. From the outset, the U.K. had a very different notion of what European integration was for, and where it should lead.

The fledgling European community of six nations was forged in 1950 after the horrors of World War II to prevent conflict from ravaging the continent again. Indeed, the call for a “kind of United States of Europe” was made by Winston Churchill four years earlier. But that founding vision required a political commitment to pool sovereignty, and for the U.K. that collided with a collective wartime memory of unity in the face of sacrifice and ultimately victory -- its finest hour. Britain has never managed to reconcile those conflicting concepts.

French President Charles de Gaulle rebuffed Britain’s first attempts to join what were then the European Communities. In a curious parallel, it was successfully admitted only at the third try -- after De Gaulle left office -- with Conservative Prime Minister Edward Heath signing the treaty of accession in 1972. A referendum on membership instigated by Harold Wilson’s Labour Party of in 1975 was carried by 67 percent in favor to 33 percent against.

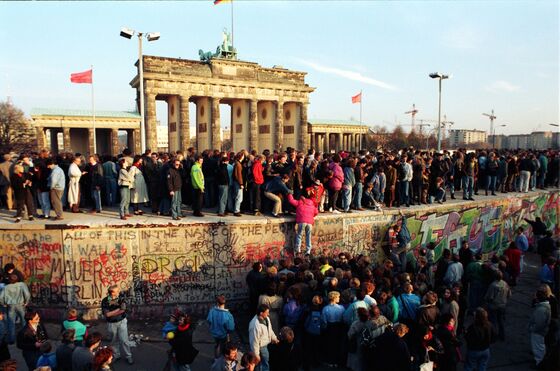

The people may have spoken but the will of the Conservative Party was far from settled. A youthful Margaret Thatcher campaigned for membership of the “Common Market,” but her faith in Europe was fundamentally altered by a singular, unforeseen event exactly 30 years ago: the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and the prospect of German reunification.

Suddenly the U.K., with its 57 million inhabitants, faced being dwarfed by a combined West and East German population of more than 78 million, politically as well as economically. The imperative was for further integration, including plans for a single European currency, the euro, as a means of binding Germany to Europe to stop it from becoming too strong. It was a tipping point, not just for Britain but for the Tories too, according to Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

At heart, “the U.K. was never on board with the political aspects of the European project,” he said. A further blow was struck in 1992 on Black Wednesday, when John Major’s Conservative government oversaw the humiliation of being kicked out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism, a precursor to the euro. The upshot was that a significant section of the Tory party “which under Thatcher had been euro-skeptic but certainly pushing for more European integration, all of a sudden became implacably anti-Europe,” said Kirkegaard.

Cameron’s Gamble

With Tony Blair’s arrival in Downing Street in 1997 came the prospect of a pro-European agenda. But Blair’s European credentials went the way of much of his early promise, crushed as Chancellor Gordon Brown blocked euro membership.

David Cameron’s coalition with the pro-European Liberal Democrats failed to prevent him from using a speech at Bloomberg’s European headquarters in 2013 to promise a referendum on EU membership as a means of staving off the euro-skeptics in his Conservative party. The die was cast, and when he unexpectedly won a majority at the 2015 election, there was no backing out of holding an in-out vote.

But even before taking the gamble that cost him his job and landed Theresa May in his place, Cameron’s approach to Europe was marked by tone-deaf acts that pandered to the euro-skeptic media at home with little thought to its impact on his continental counterparts.

Unpopular Actions

Pulling British Conservatives out of the center-right European People’s Party grouping in the European Parliament alienated potential allies such as Chancellor Angela Merkel, an act that would come back to haunt him when he sought concessions on freedom of movement to help win the referendum. Refusing to contribute to aid programs for countries such as Greece during the euro-area debt crisis added to a sense of Britain taking what it could from Europe while abandoning fellow members to their fate when in trouble.

None of this means the EU27 will be happy to see the back of Britain, assuming it happens. Germany’s powerful BGA exporters lobby, in its annual report released on Thursday, cited Brexit for a decline in exports to the U.K. of 4 percent last year. “This trend will probably intensify or at least persist in light of the further unresolved questions” over the U.K.’s plans, said the group’s president, Holger Bingmann.

Germany, the dominant EU power and its biggest economy, shares northern European traits with Britain that tend to elude France or Italy, like adhering to EU rules, implementing directives and a fondness for fiscal prudence. German Justice Minister Katarina Barley is a natural go-between: Born to a German mother and a British father, she studied in Paris, worked in Hamburg and Luxembourg, and holds dual British and German citizenship. Yet even she is showing signs of losing patience at the political pantomime.

No Clue

“We’ve seen negotiations for more than two years now, and we’ve seen delays being moved forward, and we still don’t actually have a clue on how this is going to end up,” she told Bloomberg Television on Friday morning. Europe’s prevailing sentiment is one of “astonishment,” she said. “We don’t really understand what is happening because I think there have been votes on every possible solution now, and every time the answer is ‘No’.”

Brexit-style arguments of nation versus Europe are playing out ahead of EU-wide elections to the European Parliament in May. Yet regardless of whether Britain takes part or not, none of the populist parties that rail against the EU are canvassing to follow its lead. France’s Marine Le Pen and Matteo Salvini of Italy are among those to have dropped their flirtation with ditching the euro, and even Hungary’s self-styled “illiberal” prime minister, Viktor Orban, doesn’t dare risk quitting the bloc. The EU can thank Britain’s shambolic example for that.

Never Ending

For Europe’s citizens, the moment of Brexit curiosity was fleeting and most have moved on. Brits don’t have that luxury. Next week brings another round of votes in Parliament. Even if the exit deal is agreed, the future relationship must still be hammered out. Then there’s the Irish backstop, which must be revisited in mid-2020 under the terms of the withdrawal agreement. And there’s the very real threat of fundamental changes to the entire British political system, buckling under the all-consuming strain of Brexit.

“This is non-stop, it’s not going to change, we’re going to have exactly the same kind of debates happening as we have right now,” said Kirkegaard. “It’s basically not going to end.”

--With assistance from Chris Reiter.

To contact the reporter on this story: Alan Crawford in Berlin at acrawford6@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Rosalind Mathieson at rmathieson3@bloomberg.net, Andrew Atkinson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.