Brexit Reopens Question of United Ireland Decades After Conflict

Brexit Reopens Question of United Ireland Decades After Conflict

(Bloomberg) -- In Enniskillen, a town once synonymous with the civil conflict that made Northern Ireland one of the world’s trouble spots, Gráinne Knox and her husband rarely talked about the prospect of a united Ireland.

The 35-year old illustrator comes from a family that’s traditionally republican, or supportive of reunifying the U.K. province with Ireland to the south. He is from the other side of the divide, the unionists who have wanted the region to stay British. But for two people who came of age around the time of a peace deal, it was hardly a burning issue.

Then Britain voted to leave the European Union. The most emotive of Irish questions is now creeping back into pubs and living rooms, one that politicians in London, Dublin and Belfast have been eager to avoid so as to not destabilize the fragile region. Even though there’s little prospect of triggering a process of reunification anytime soon, just the fact that it’s being discussed is testament to the political forces that Brexit has unleashed across the U.K.

“Brexit has dragged the subject out from the back of the cupboard where I think secretly many people were happy enough for it to remain,” said Knox. “There’s no denying that Brexit has opened up a space in the national dialogue for this conversation to happen.”

Like the majority of voters in Northern Ireland, both Knox and her husband cast their ballot to stay in the EU in the referendum three years ago. Now their discussion is over whether it makes sense to remain in the U.K. should a vote ever happen on uniting Ireland’s north and south.

One potential game changer is Scotland, which also voted against Brexit, albeit more emphatically. Across the Irish Sea, the pro-independence party that runs the semi-autonomous government in Edinburgh is pushing for another vote on whether to remain in the U.K. and polls show the outcome would be too close to call.

Just this week, David Lidington, Britain’s de facto deputy prime minister, warned government ministers that leaving the EU without a deal could spell the breakup of the U.K. as Scotland seeks independence and Irish reunification gains traction. Boris Johnson, the front runner to become the next prime minister, has said he’s prepared to deliver Brexit come what may by Oct. 31, the latest deadline after three years of deadlock.

The time isn’t right for a vote in Northern Ireland, according to Martin Mansergh, a former Irish senator who was a government adviser during the negotiation of the Good Friday Agreement in 1998 that largely ended the conflict in the province. But events elsewhere could ultimately dictate what happens in the future.

“A successful Scottish independence referendum – and that might happen under a Boris premiership – could change the equation,” said Mansergh. “Change can meander slowly, but then accelerate quickly.”

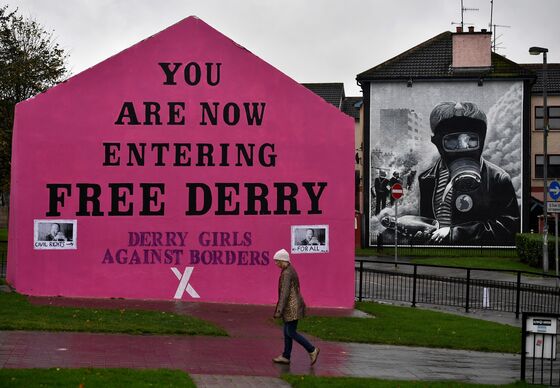

Until now, the island of Ireland has been a sticking point in Brexit talks for different reasons: how to keep the border open. The 310-mile (500-kilometer) frontier running from near Derry, or Londonderry, in the north to Dundalk in the south will form the EU’s only land border with the U.K. after Brexit.

The U.K. effectively split the country in 1921 to placate a largely Protestant, unionist majority in the north in the face of increasingly militant demands from the Catholic-dominated south for independence from Britain.

By the turn of the 1970s, tension morphed into violence between sectarian groups that left more than 3,500 people dead. Even now, on every July 12, the Protestant Orange Order holds controversial parades in Northern Ireland to celebrate the victory of the Protestant King William over the Roman Catholic King James II at the Battle of the Boyne in the 17th century.

But the border is pretty much invisible. The fact Ireland and the U.K. were both members of Europe’s single market meant there was little need for checkpoints. Moreover, under the Good Friday Agreement, Northern Ireland’s 1.8 million people are entitled to an Irish passport, a British passport or both.

Crucially, the agreement also states that the U.K. government can only call a unification referendum when it considers it likely a vote would be carried. As yet, there’s no sign of a majority in that direction, polling shows. A messy Brexit might influence that, according to Diarmaid Ferriter, professor of history at University College Dublin and author of the 2019 book, “The Border.”

“I can see a poll in the next few years because of the chaos in the U.K., and a united Ireland in our lifetime,” he said. “But there are so many questions still to be answered.”

Indeed, the Brexit vote reignited still-simmering sectarian tensions. While the pro-U.K. Democratic Unionist Party campaigned to exit the EU, the nationalist Sinn Fein opposed it. In the end, 56% chose to remain. U.K.-wide, though, the result was 52% in favor of leaving.

Both sides have deployed the Irish unification card. Sinn Fein have called for a referendum while British Prime Minister Theresa May evoked the risk to the union in her failed bid to gain parliamentary backing for her Brexit agreement.

“To an extent, the notion of a border poll has been pushed up the agenda by different parties in the context of so much uncertainty around Brexit,” said Mansergh. “The question is whether there’s sufficient support even amongst a minority of unionists for a poll. The danger is an ill-thought out referendum without a clear and agreed plan for what happens afterwards, and which sends the two sides back into their trenches and squeezes any middle ground.”

As he watches events unfold in Northern Ireland, Christopher Finlay is wary of the dangers that might flow from a vote that didn’t command widespread support, including the possibility of renewed violence.

From a unionist background in the town of Omagh, the 45-year-old is now professor of political theory at Durham University in northeast England. He sees Brexit as largely an “English nationalist project” that dismisses the views of Northern Ireland and Scotland.

“Before the Brexit referendum, I don’t imagine I would have voted for a united Ireland,” he said. “Now, my mind is more open on the question. I suspect I’m not alone in that.”

Back in Enniskillen, about 15 miles from the Irish border, there’s a poignant reminder of the dark days before the Good Friday Agreement and the EU’s efforts to foster peace by plowing aid into Northern Ireland. In one of the most notorious terrorist attacks during the sectarian conflict, an Irish Republican Army bomb on Remembrance Day in November 1987 killed a dozen people.

Knox said she’d vote for a united Ireland if it meant it would protect her rights as an EU citizen. Others would follow once the reality of a hard Brexit hits, she predicted.

“If voting for a United Ireland meant I could definitely have my rights as a European citizen protected, I’d be there with bells on,” she said. “I think many others feel the same.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Emma Ross-Thomas at erossthomas@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.