Brexit Is Bringing Out the Worst in Britain

It’s a five-minute walk from the Houses of Parliament in London to the spot where Great Britain was last at its greatest.

It’s a five-minute walk from the Houses of Parliament in London to the spot where Great Britain was last at its greatest.

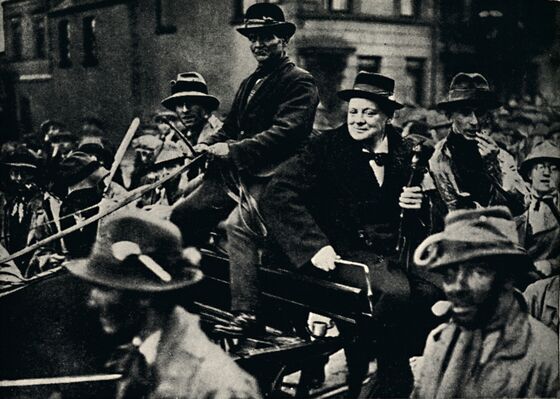

Squeezed between the Treasury and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, a discreet set of steps leads down to a bunker complex that served as Winston Churchill’s underground command center during World War II. It’s here that the country’s most vaunted prime minister, the War Cabinet and chiefs of staff worked and slept, sifted intelligence, plotted campaigns and ultimately helped turn the tide of the war against Nazi Germany.

What Churchill famously referred to as Britain’s finest hour is invoked nostalgically in the U.K. among those pressing to leave the European Union. But as another deadline to depart the EU comes and goes, the prolonged uncertainty over Britain’s future is instead bringing out the worst of the British character on both sides of the Brexit divide.

The animosity threatens the most bitter election campaign in memory over the next six weeks as delivering or preventing Brexit become ideologies in themselves. The normalization of bellicose language directed at opponents both at home and abroad suggests the postwar model of a liberal, internationalist Britain has had its day.

Instead, slurs are directed at Ireland for not bowing to British demands. There are threats to withhold money due to the EU. Cooperation with member states on security matters is seen as a bargaining chip.

Even as some politicians try to calm the rhetoric in the House of Commons, the public has gone the other way. Whether it’s death threats to members of Parliament, marches in London or radio phone-ins and the BBC’s flagship Question Time show, the impression now is of a country bristling with Brexit-induced aggression.

At least two MPs, Culture Secretary Nicky Morgan and former Conservative Heidi Allen, cited abuse for doing their job when announcing they would stand down and not contest the election.

Majorities in England, Scotland and Wales told the Future of England Survey released on Oct. 24 that violence toward MPs was a “price worth paying” to achieve their Brexit aims. Shaken by his survey’s findings, Richard Wyn Jones, a politics professor at Cardiff University, warned that “further polarization could be a deliberate campaign strategy for some parties.”

In Northern Ireland, the police chief has warned of the prospect of public disorder because of loyalist outrage at what they regard as a weakening of ties to the rest of the U.K. as a result of Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s renegotiated deal with the EU.

Britain, of course, is no stranger to violence. Whether it’s building a global empire or pub fights between rival soccer fans, there’s always been an edge to the national psyche. But it’s also been a magnet for immigrants with a reputation for tolerance. The first purpose-built mosque, for example, came in the late 19th century.

It’s the ugly side that’s dominating now, though. More than three years on from the 2016 referendum, the language of Brexit has become more deliberately confrontational.

Johnson, who said he’d “rather be dead in a ditch” than request an extension to the Oct. 31 departure date, blames the “zombie Parliament” for frustrating his bid to quit the EU. He refers to opposition surrender to Europe, and accuses Parliament of holding the country “hostage.” Challenged, Johnson dismissed concerns over his language as “humbug.”

The pro-Brexit press routinely labels lawmakers and judges traitors, while campaign group Leave.EU made an explicit link between Brexit and the war in a Twitter post this month that referred to Chancellor Angela Merkel as a “kraut.” It shrugged off the ensuing storm and deleted the tweet.

There are real world consequences: The risk is the U.K. will alienate allies just when it needs them most—to sign trade deals, grease international collaboration and, not least, foster goodwill toward a middling power cutting loose from a bloc of 500 million people of which it’s been a part since 1973.

“Britain’s reputation has obviously suffered,” said Eoin O’Malley, a political scientist at Dublin City University, who cites “a breakdown of trust where normal diplomatic language is not being used.”

Nowhere outside Brussels has been the subject of as much righteous British anger as Ireland, with widespread incredulity that the Irish government could wield so much influence in the Brexit process.

Conservative lawmaker Priti Patel denied suggesting to a newspaper that the threat of food shortages in the event of a no-deal Brexit might encourage Ireland—which suffered devastating famine in the 19th century when under British rule—to bend to the U.K. Patel said she’d been quoted out of context, and was promoted by Johnson to home secretary.

The vitriol is not all one way. A Twitter hashtag, the #BritsAreAtItAgain, has surfaced in Ireland, under which tweets are posted taking offence at all manner of supposed British sleights.

To academic O’Malley, the hashtag with its undertones of Ireland’s struggle for independence is evidence of an increase in anti-Britishness in response to Brexit. And even with a December election on the horizon, “it's hard to see a government in the U.K. in the near future that will benefit Britain or Ireland,” he said.

Indeed, there’s a danger that Brexit is resetting Britain’s foreign relations to before the postwar reconciliation and European unity to an earlier time of great rivalry.

For Diane Purkiss, professor of English literature at Oxford University and a historian of the English Civil War, Brexit is triggering a return to imperial type. With its pursuit of Brexit, Britain has “trashed its international reputation” and the government is now viewed in the same terms as “its colonies have always seen it,” she said.

“There’s a sense in which everywhere that Britain has actually ruled has long understood how difficult it is to negotiate with Britain, how difficult it is to be listened to by Britain, and how arrogant and violent the British become when you try,” she said.

It’s a set of circumstances that might have been familiar to Churchill. Born in 1874, when Britain ruled a vast empire under Queen Victoria, he was adamant that everything should be done to maintain the U.K.’s status as an imperial power. Celebrated as a visionary war leader in the U.K., his image—and that of Britain—is far more controversial in those parts of the world that recall him for different reasons.

In Ireland, he deployed a brutal auxiliary force to suppress home rule. As Secretary of State for the Colonies in the 1920s, he implemented British policy to carve up the Middle East, sowing the seeds of the Israel-Palestinian dispute. And he opposed Indian self-rule, accusing Mahatma Gandhi of being a “seditious fakir.”

Strolling down Whitehall past Downing Street and Britain’s grand offices of state, it’s not hard to imagine the U.K. thriving free of the EU institutions that are so locked into the postwar politics of Berlin, Rome or Paris.

Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab said Britain wanted to be friends with Europe, but also “buccaneering global free traders,” he wrote in an article for the Sunday Telegraph published on Sept. 23.

The Foreign Office is itself a reminder of Britain’s former globalism. At the time of its opening in 1868, it housed the India Office, complete with lavish gilding, doors, furniture and a marble fireplace taken from the headquarters of the former East India Company, the original global free traders who employed a private army to appropriate the subcontinent’s wealth before the crown muscled in.

The chimney piece, dating from 1730, has a panel showing “Britannia, seated by the sea, receiving the riches of the East Indies.” It’s both an expression of Britain’s former global trading power and a reminder that it didn’t amass an empire by being nice to other nations.

What kind of image Britain will project post-Brexit is open to question. During the referendum campaign, Johnson, Churchill’s biographer, said that “sunlit meadows” would be ushered in by a vote to leave the EU. That was a play on Churchill’s “finest hour” speech in which he exhorted Britain and her allies to stand up to Hitler and “move forward into broad, sunlit uplands.”

“Get Brexit done” is now Johnson’s refrain. And as he fights an election that will be defined by Brexit, he might reflect on the fate of his hero: In 1945, having won the war, Churchill was voted out of office.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rodney Jefferson at r.jefferson@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.