Bolsonaro Makes Upstart Evangelical Network Brazil's Must-See TV

Bolsonaro Makes Upstart Evangelical Network Brazil's Must-See TV

(Bloomberg) -- Jair Bolsonaro began his first interview as Brazil’s president-elect by thanking the reporter for his network’s impartiality.

Whether that’s the best way to characterize Grupo Record’s coverage is debatable; the media conglomerate says its work is unbiased, but some journalists told their union they faced pressure to favor Bolsonaro after an endorsement by the owner, a billionaire evangelical bishop.

What’s clear is Bolsonaro’s preference for the network jockeying to consolidate its standing as Brazil’s second-most-watched. On election night Oct. 28, Bolsonaro granted Record exclusive access to his home, where the seven-term lawmaker, his family and allies watched results come in on the company’s television channel. The network has had the most post-election interviews, and they’re the only ones Bolsonaro shared in their entirety with his millions of social-media followers as he prepares to take office Jan. 1.

The arrangement recognizes the increasing sway of evangelicals in a nation that once was monolithically Catholic, and allows Bolsonaro to trumpet talking points to a receptive audience and bolster his far-right agenda -- all the while increasing Record’s clout. An admirer of Twitter-happy U.S. President Donald Trump, Bolsonaro has repeatedly sown distrust of major media outlets like the ubiquitous Globo group and enjoys a direct line of communication to his supporters. But, like Fox News to Trump, Record is shaping up as a safe space for Bolsonaro.

Previously Indispensable

“Record could gain more influence on the government, more access to power; that’s worth much more than advertising in the Brazilian political game,” said Eugenio Bucci, a columnist for Estado de S. Paulo and a communications professor. “It could gain first-hand news, higher status, and come to be seen as the federal government’s preferred network. If that happens, it advances a few steps in the competition with Globo.”

Winning the favor of Rio-based Grupo Globo, owned by the Marinho family and encompassing magazines, radio stations and television channels, has historically been seen as a prerequisite to the presidency. One former president said that he’d tangle with anyone, even the pope, but not Globo’s owner.

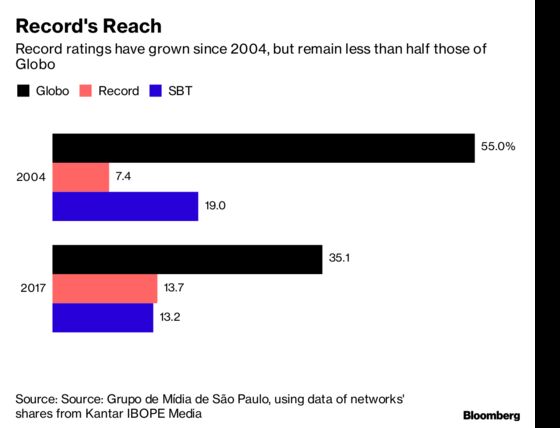

While Globo’s dominance is less than in decades past, its flagship network still posts more than double the ratings of its next-closest competitors, Record and SBT. With that heft comes benefits; between 2000 and 2016, it received almost half the television ads bought by government and state-owned enterprises, according to the now-defunct Institute for the Monitoring of Publicity.

Bolsonaro has allowed Globo into news conferences and granted it one post-election interview -- albeit allotting less than half the time of Record on the same day. But the president-elect has an unprecedented ability to circumvent the company thanks to his immense social-media following and the support of evangelical pastors and their congregations that reach into the tens of millions.

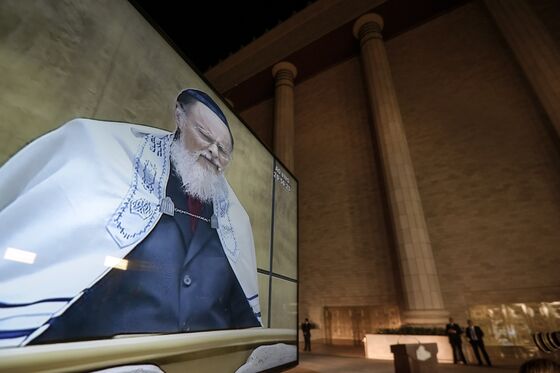

No endorsement was more valuable than that of Edir Macedo, the 73-year-old self-proclaimed bishop of the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God. Macedo owns Record, which in addition to a broadcast station controls more than 100 television affiliates in 26 states, plus radio outlets.

Days after Macedo voiced his support, Record scored an exclusive interview with Bolsonaro. It then proceeded to air it during Globo’s presidential debate, which Bolsonaro didn’t attend, despite being the front-runner. The power move gutted Globo’s ratings that night.

To read more: Evangelical Pastor Turns Billionaire on Tithes From Brazil Poor

Macedo’s media conglomerate quickly shifted coverage, featuring mainly stories that flattered Bolsonaro; Paulo Zocchi, the president of Sao Paulo’s journalist union, said he received complaints from Record employees who said they were pressured to favor the candidate before the election.

The network’s run-of-the-mill coverage rarely challenges. An anchor kicked off a Monday segment about the expulsion of Cuban doctors by affirming Bolsonaro’s claim that Brazil never needed them. But the report omitted the reason for the program’s existence: the historic difficulty of persuading Brazilian professionals to take jobs in rural areas. Bolsonaro soon shared the report on social media.

“It seems Record will be part of Bolsonaro’s strategy of creating a certain bulwark to protect himself from criticism by other media,” said Fabio Vasconcellos, a political scientist who teaches communications at Rio de Janeiro’s state university.

Asked by Bloomberg about the apparent preference for Record, a press adviser for Bolsonaro, Tercio Arnaud Tomaz, told Bloomberg the president-elect still hasn’t chosen anyone to define a systematic communications strategy.

Globo declined to comment when contacted by Bloomberg News.

Entrepreneurial Religion

For its part, Record pointed to a previous statement repudiating “cowardly attacks” on its coverage, saying it has more than 30 years of credibility, and its employees provide clear and unbiased facts. Further, it said Macedo’s support of Bolsonaro in no way influenced its editorial choices.

Macedo’s ascension to media baron has been unique, having built his empire from the ground up, preaching first in rented space inside an old funeral parlor, then run-down halls. The more parishioners tithed, he told them, the greater their blessings.

His ambition was mirrored in the expansion of Record, a station on the brink of bankruptcy when he bought it in 1989. Today, it is prominent nationwide, especially in Brazil’s vast, rural interior. Its programming includes shows such as the wildly successful telenovela “The Ten Commandments,” and Universal Church sermons that play on until the wee hours. The channel also broadcasts sensational crime shows full of wandering helicopter shots searching for missing bodies, and reality programming akin to “Big Brother.”

Record’s news programs mirror Globo’s two major current-events offerings, the daily “Jornal Nacional” and Sunday’s “Fantastico,” echoing their form if not their content.

Street Hassle

Bolsonaro, who has repeatedly said he believes in press freedom, has also promised that his administration will cease placing ads in media that publish fake news -- and called out Globo as a beneficiary of that spending. Globo said in a statement only 4 percent of its ad revenue comes from the public sector.

By election night, the effect of Bolsonaro’s preference for Record -- and vice versa -- was clear on the streets. Supporters in Rio harassed journalists from other publications as they interviewed one of Bolsonaro’s chief advisers and called for him to speak only with Record. Weeks later, reporters camped outside Bolsonaro’s home still hear hecklers in passing cars shout “Globo trash!” and “Globo, the racket is over!”

Bolsonaro’s approach appears aimed at compelling restraint in order to avoid an overt crackdown, said Michael Shifter, president of the Inter-American Dialogue, a Washington think tank.

“There are interesting parallels with Trump; a lot of news outlets that started out being more restrained, and that gave them access, are now in kind of open war with Trump, CNN being the biggest example,” Shifter said. “I bet all these media outlets are trying to figure out how to deal with this situation. Do they want to be cut out, do they want to be part of it, and if so how do they position themselves?”

Indeed, executives from other outlets are following Macedo’s lead and cozying up. Silvio Santos, the owner of SBT and presenter of its most popular show, told Bolsonaro on air that he supports him and hopes he wins a second term. The vice president of a smaller network, RedeTV!, followed suit days later.

Gabriel Priolli, a journalist who’s worked for various media including Globo and Record and coordinated a study about Globo’s waning influence, said the power of Bolsonaro, a former paratrooper, exerts a pull.

“Everyone’s offering themselves up to be the captain’s network, his big communication structure,” he said. “That’s the game being played.”

To contact the reporters on this story: David Biller in Rio de Janeiro at dbiller1@bloomberg.net;R.T. Watson in Rio de Janeiro at rwatson71@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Vivianne Rodrigues at vrodrigues3@bloomberg.net, Stephen Merelman, Robert Jameson

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.