An Online Army Is Drumming Up Support for a French Extremist

“Eric Zemmour is saturating the social media space,” says a research manager from Institute for Strategic Dialogue in London.

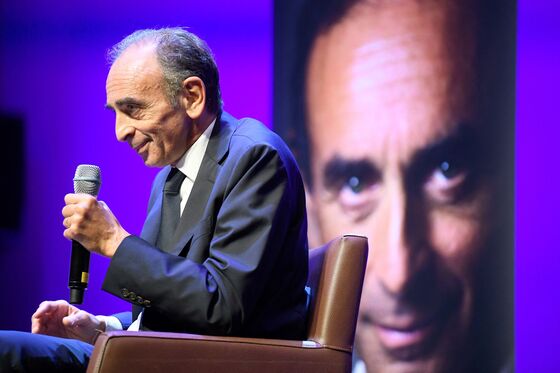

(Bloomberg) -- Ultra-conservative pundit Eric Zemmour has been a fascination in certain far-right circles for at least a decade, but this year he has been elevated to a kind of cult status among French-language Facebook groups, Twitter discussions and other online spaces.

As he keeps voters guessing about whether he’ll fight President Emmanuel Macron for his job in the April election, a whole online ecosystem has been built around the best-selling author and television star on France’s answer to Fox News.

The model works much the same way as the coalition of interests on social media that cheered Donald Trump in the months before the 2016 election in the U.S. Some groups have links to websites that promote hate speech, posts appear coordinated and it’s not clear who’s behind them.

This sort of support may have once been dismissed as a distraction, but Trump’s victory, and all the events that followed, mean that is no longer so easy.

“Zemmour is saturating the social media space,” says Cécile Simmons, a research manager at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue in London. “He is generating more engagement online than any other declared candidate by stirring controversies and making outrageous claims, which social media algorithms amplify.”

“Active online communities of supporters (including Gen Z users) have flourished,” Simmons says.

The use of social media to propel a candidate into office has formed a part of political campaigns for both mainstream and fringe contenders around the world since at least Barack Obama’s 2008 election. In markets where the use of traditional media was often tightly regulated, social platforms often offered politicians and their supporters the chance to communicate in new and more direct ways.

This has been as true in France as anywhere else. Zemmour isn’t even the first far-right figure to be the beneficiary of a social media campaign. In 2017, Marine Le Pen attracted attention for her insurgent approach that made liberal use of digital platforms. Indeed, on Twitter followers alone, her 2.6 million verified Twitter account still dwarfs the 300,000 Zemmour’s unverified profile had at the time of writing.

Yet focusing on numbers does not capture the new reality in which next year’s presidential campaign is taking place. The Fachosphère, a French term used to refer to the far-right Internet, has been around since the mid-noughties, but the rise of figures such as Trump, and platforms such as Facebook have given renewed force to populist groups online. Beliefs that begin in one country can make their way across the world quicker than ever before, as seen with the spread of anti-vaccine and anti-Covid misinformation during the pandemic.

“Zemmour with his emphasis on the great replacement sounds an awful lot like Tucker Carlson and Trump’s MAGA base,” says Angelo Carusone, president of Media Matters for America, a non-profit organization. “Tucker and Zemmour are refracting the energy and sentiments of this deeper, international, interconnected far-right power base.”

Nowhere is this support for Zemmour more evident than on Meta’s Facebook, where his popularity exploded over the last 18 months. A search by Bloomberg found several groups that had been created since the start of 2020 with an explicit goal of promoting his candidacy in the 2022 election. Many have accrued thousands of followers, with at least two attracting more than 10,000 members a piece at the time of writing.

An official page with 75,000 likes at the time of writing blasts out a stream of posts promoting Zemmour’s appearances and work, which is then amplified by a wider network of groups and pages. Often the posts themselves begin relatively innocuously, then take on a new meaning once they are diffused among the wider network.

The ownership of many of the broader groups and pages is unclear. At least one example seen by Bloomberg has connections to white supremacy. Posts in the group, which is not being named here to avoid promoting the site, was started by a page with links to a website against inter-racial marriage. While the posts on Facebook do not appear to have fallen afoul of the platform’s rules, the website makes several unsubstantiated claims based on race.

Meta has been in the news following disclosures by whistleblower Frances Haugen. A former employee on its integrity team, Haugen released a selection of internal documents to Congress, which were later handed to a consortium of media outlets. The documents have been the basis of several news stories by the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg, and other organizations.

While France is only sporadically mentioned within the cache, the posts have lent weight to the perception that the company applies inconsistent standards to harmful content in non-English languages, something that the company has denied in comments to Bloomberg. “We are on track to spend more than $5 billion this year alone on safety and security — more than any other tech company — and have 40,000 people to do one job: keep people safe on our apps in more countries and more languages around the world, including in France,” the company said.

For all Zemmour’s popularity on Meta, however, it is just one of several social networks where the pundit’s presence is felt. Twitter, too, has seen a particularly fervent outpouring of support for him.

Like they do on Meta’s Facebook, accounts with names such as ‘Women With Zemmour’ ( Les Femmes Avec Zemmour) and ‘The Young with Zemmour’ (Les Jeunes avec Zemmour) promote his public appearances and amplify his messaging. Often, the accounts follow similar themes and initiatives. In early June, as posters promoting Zemmour’s candidacy suddenly appeared on the streets of Paris, the social media accounts all shared a link to a petition calling for him to run.

Often, there’s even less clarity about who is behind these accounts than similar pages on Facebook. Most were created between April and May this year, with one early example seen by Bloomberg dating back to February. Despite sharing branding and posting style with a number of other pages within their wider network, these accounts rarely push their audiences to other platforms. Instead, content is tailored directly for followers on Twitter. Images are cropped horizontally, and clips are edited down.

Yet the campaigns aren’t all working in Zemmour’s favor.

On fringe social networks such as Parler and Gab, where there are less restrictions on anti-Semitism and white supremacy, something of a resistance is forming. Unlike Trump, who notably attracted support from across the far-right spectrum, there are certain users who remain suspicious of Zemmour’s motives. They point to his Jewish and North African heritage as proof that his anti-immigrant stance is just a ploy to get into office and argue that he will reverse tack once he is elected.

“Despite some parallels, Zemmour is still a very different type of politician to Donald Trump,” the ISD’s Simmons says. “He has been a contributor to political debate for a number of years as a journalist, pamphleteer and commentator whereas Trump was newer to the political discussion when he emerged as a presidential contender.”

“The key issue has less to do with whether Zemmour wins or loses,” Simmons adds. “But more the extent to which he will shape political debate during the campaign and introduce his ideology into the mainstream of French society.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.