Add a Million Venezuelans and Your Economy Looks Very Different

Add a Million Venezuelans and Your Economy Looks Very Different

(Bloomberg) -- Markets were shocked when Chile cut interest rates this month, but the central bank had a simple explanation: The economy suddenly had a lot more people in it.

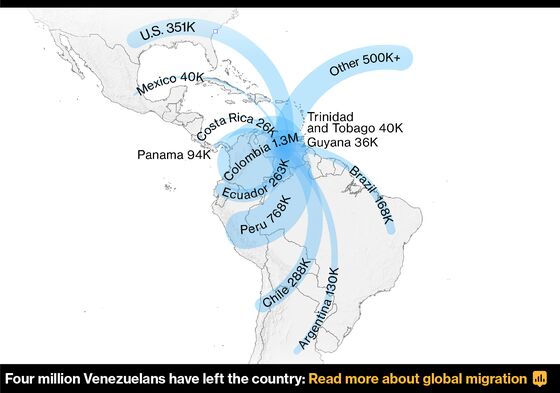

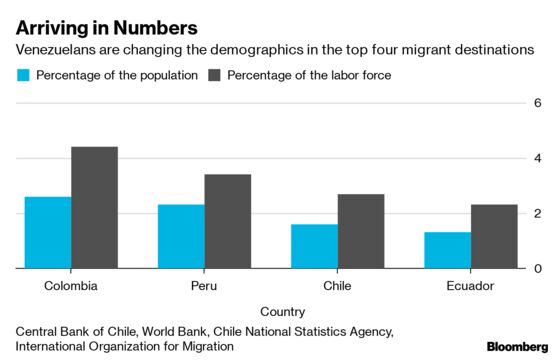

That’s because of the exodus from Venezuela, where about 4 million people have fled financial and social collapse. They’re showing up across South America, forcing central banks and finance ministries to deal with the economic consequences.

Host countries have to find cash for health-care and education, and international aid doesn’t come close to covering their costs. That’s causing budget problems for Colombia and Peru, where the influx has been biggest. And there are signs of a public backlash in many countries, as the new arrivals compete for jobs.

The Chilean case shows potential benefits too, at least in the longer run, as policy makers explained after their interest-rate surprise. Boiling down the central-bank-speak, the argument was: there are more people available to work, even if they’re not yet doing so. That makes room for the economy to grow without pushing prices higher. The catch, especially for workers, is that there’ll be downward pressure on wages too.

“It’s an expansion of potential GDP,’’ said Alberto Ramos, the chief Latin America economist at Goldman Sachs. “It’s a shock to the labor force that isn’t inflationary.’’

Whether countries can take advantage, says Ramos, “depends on how immigrants integrate’’ –- and especially, whether they end up in tax-paying jobs or the black economy.

‘They’re Adapting’

Government policy can make a difference. Chile is probably in the lead.

Take the experience of Vivian Montes, a 27-year-old Venezuelan who arrived via Brazil. She’s a human-resources professional, and found work in Santiago with a large international company.

Her network of fellow Venezuelans helped –- but so did Chilean rules. The labor market is relatively light on red tape, and Montes says officials and companies have proved flexible.

“When I first arrived, Chileans didn’t understand the process migrants need to go through to obtain a work visa,’’ she said. “But so many of us have arrived that they are now adapting.’’ As a result, more migrants move on to jobs in their own profession, instead of getting stuck in lower-paid service industries.

Adding up tens of thousands of stories like Montes’, Chile’s central bank arrived at a higher estimate for economic growth in the medium term.

The bank -– which had previously sounded hawkish -- said rapid immigration has boosted potential output while easing upward pressure on wages and prices. That’s what enabled the biggest interest-rate cut in a decade, almost entirely unforeseen by economists.

‘Most Vulnerable’

But Chile has had an easier task than some neighbors, with smaller numbers arriving.

Plus, it’s the continent’s richest country, with robust public finances. And geography dictates that it attracts wealthier Venezuelans, said Andrew Selee, president of the Migration Policy Institute in Washington.

“The southern cone is receiving the migrants who have the most resources, a very well-educated group,’’ he said. “The most vulnerable populations, the most sick or who have malnutrition, are not going to be able to travel the distance.’’

They’re likelier to end up in Colombia or Peru.

Peru’s central bank says immigration may have lowered inflation, as Venezuelans push down wages in retail and other services –- while their consumption added 0.3 percentage point of economic growth last year.

What Our Economists Say

“Chile’s central bank has been struggling with persistent low inflation, and the migrant flow helps explain why. It is consistent with higher potential growth, which implies a wider negative output gap and less inflationary pressure.

In Peru, the impact of immigration has the same effect of containing inflation. But despite it, inflation has increased and is close to the ceiling of the target, so the central bank has no room to cut interest rates.”

--Felipe Hernandez, Latin America economist at Bloomberg Economics

But over at the Finance Ministry, the strain is apparent.

Spending on health and education has increased, but not by enough to prevent lengthening lines at hospitals and bursting classrooms in schools, said Finance Minister Carlos Oliva. “Even without Venezuelans, we have a serious problem with the provision of basic public services.’’

‘I Wish...’

It’s tough for Venezuelans to get jobs where they pay the taxes that help finance those services. Even most Peruvians don’t manage it. About seven in 10 work in the informal sector. Half of the country’s Venezuelan migrants have work permits, but only some 5% were officially employed as of April.

That also means Venezuelans end up in jobs they’re overqualified for –- capping the boost to the economy.

Angel Sabino, 37, says he misses working as an electrician at a Coca-Cola bottling plant in Venezuela. Learning about new machines kept him active, and pay and benefits were good, until they were eaten up by hyperinflation. He left last year, and now works as a concierge in Lima.

“I wish I had the opportunity to earn a little more working in my profession,’’ he said. But, “if you don’t know someone, it’s very unlikely the company’s going to call you. And if you find a job, they pay you less. They don’t pay you like a Peruvian.’’

Because they’re lower down the pay scale, migrants like Sabino compete with larger numbers of native workers. It can cause friction. Peru’s Cusco Region approved a rule last month to sanction employers who fired Peruvians to hire Venezuelans.

Pay Up-Front

It’s in Colombia that the political and financial strains are probably most acute.

Competition from migrants is squeezing pay for low-skilled workers, the World Bank says. There are signs of brewing discontent.

An audio message circulated last year in Subachoque, north of the capital, threatened any Venezuelan who didn’t get out of town within two weeks. In October, in a poor Bogota neighborhood, a migrant was beaten to death by a mob shouting xenophobic slurs.

The government estimates it has paid $1.5 billion, 0.5% of GDP, to look after fleeing Venezuelans. It’s borrowing $700 million from the World Bank to help smooth the impact. But in April, a donor drive organized by the Bank raised just $31.5 million, about $25 per migrant.

Alberto Rodriguez, a director at the World Bank, said there’ll be a bigger boost to demand from Venezuelans once they settle in their new countries. He said Colombia and Peru, especially, can benefit from the higher productivity of the new arrivals.

You have to take the long-term view to grasp the benefits of migration in general, according to Selee in Washington -- because they’re not always immediately evident.

“It spurs innovation and growth,’’ he said. But, “when there are large-scale flows like this one, there are up-front costs.’’

--With assistance from Sebastian Boyd.

To contact the reporters on this story: Daniela Guzman in Santiago at dguzman26@bloomberg.net;John Quigley in Lima at jquigley8@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Juan Pablo Spinetto at jspinetto@bloomberg.net, Ben Holland, Robert Jameson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.