A Former Pariah That Hosted Bin Laden Courts Global Approval

A Former Pariah That Hosted Bin Laden Now Courts Global Approval

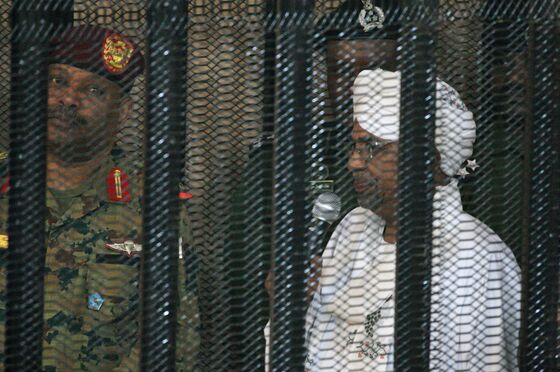

(Bloomberg) -- Led by a suspected war criminal who once hosted Osama bin Laden, Sudan’s reputation could only improve when the government was overthrown last year.

Yet by any metric, the North African nation hit with crippling sanctions for allegedly supporting terrorism under Omar al-Bashir has made a startling turnaround. Its former dictator may face international justice, Sudan is paying compensation to U.S. citizens for a 2000 attack in Yemen, and -- perhaps most remarkable of all -- the idea of relations with long-time foe Israel is no longer taboo.

After three decades of firebrand Islamist governance and alliances with Washington’s enemies that made their nation a pariah, Sudanese have welcomed at least some of the moves. But there’s pragmatism, too, as Sudan’s new rulers lobby the U.S. to drop its long-standing listing as a sponsor of terrorism, a step crucial to rescuing the shattered economy.

“There is very little this government isn’t willing to do to get on the right side of the U.S.,” said Cameron Hudson, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and a former State Department official.

Any sustained U.S. rapprochement with Sudan would be a turnaround with little international precedent in recent decades. Bringing the third-most populous member of the Arab League onside would give Washington a strategic triumph in Africa, where it’s vying with one-time Bashir supporters Russia and China for influence, while adding another ally on the Red Sea, a choke-point for global shipping.

Past thaws with steadfast U.S. opponents, including Syria and Iran, have been temporary and soon reversed, some by conflict and others following Donald Trump’s ascension to the presidency.

In Africa’s third-largest country, though, the fall of Bashir has changed almost everything. The government of civilians and army-men who’re steering it toward 2022 elections may be a divided bunch, but they agree on at least one thing: Sudan badly needs to improve its image.

Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok, who has said Sudan needs billions of dollars to head off a crisis, has made courting the U.S. one of his major goals. Images of him joking with U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo during a visit to Germany this month were widely circulated at home to popular approval. “Thank you, Hamdok” is a common protesters’ chant and a popular scrawl of graffiti in Khartoum.

Economic ‘Lifeline’

“The U.S. now realizes that lifting the state sponsor of terrorism designation is the lifeline that Sudan needs to avoid financial collapse,” Cameron said. That process, however, can be a long one, requiring an assessment by the intelligence community and Congressional approval.

Sudan’s international isolation began soon after Bashir seized power in a 1989 and quickly implemented a hard-line interpretation of Islamic law that sought to make the country the “vanguard of the Islamic world.” Al-Qaeda and Carlos the Jackal settled there; the U.S. designated Sudan a terror sponsor in 1993, later imposing sanctions until 2017.

While Bashir eventually expelled Bin Laden and cooperated with the U.S. after the Sept. 11, 2001, terror attacks, his bid to crush a rebellion in Sudan’s western region of Darfur cemented his notoriety.

The International Criminal Court indicted him for alleged crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes -- a step that restricted his global movements, although he managed trips to Russia, China and much of the Middle East and Africa.

Sudan was already making cautious steps toward rapprochement in the final years of Bashir’s rule. In 2015, the government drastically cut back ties with Iran that had been based on a shared taste for revolutionary Islam, joining the Saudi Arabia-led alliance battling rebels across the Red Sea in Yemen.

The 2011 secession of South Sudan, which saw Khartoum lose three-quarters of the formerly united country’s oil reserves, shocked Sudan’s economy, spurring sporadic protests over living costs that eventually built to a nationwide movement opposed to his oppressive rule.

Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, which had previously helped Sudan with loans and deposits, pledged their support in early 2019. But it was only after army and security chiefs ousted Bashir in April that they committed serious funds.

Many Sudanese are wary of the Gulf influence and question how committed Bashir’s ex-enforcers in the current government such as army chief Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and militia leader Mohammed Hamdan are to surrendering power. Hamdan’s fighters stand accused of massacring more than 100 people at a protest camp last summer, as well as attacks in Darfur in recent months.

Washington is really waiting for signs of the government’s willingness “to take hard decisions that challenge the supremacy of the military and commit the country to a less reversible democratic path,” said Hudson.

In the meantime, the efforts to court the international community have come thick and fast. The German president visited Sudan on Thursday, the highest-ranking Western government official to do so since Bashir’s fall.

“We need to show the world and to prove to them that the new Sudan after the revolution is a democratic place, and conducive to investments, tourism and other forms of engagement,” says Information Minister Faisal Mohamed Salih.Earlier in February, the transitional government indicated Bashir would face the ICC as part of a deal with rebels, though questions were raised over whether Sudan would extradite him to the Netherlands-based court or try him at home, and if both civilian and military arms of government agreed.

“We are committed that all wanted people, including Bashir, will stand before the court,” said Salih.

The ICC initiative shortly after a perhaps even greater shock: Al-Burhan met Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu during a trip to Uganda and pledged to work toward normalizing relations -- something no government of Sudan since independence in 1956 has ever officially done.

“Overt Israeli endorsement of a lift for Sudan will provide a key push to the U.S. government,” said Jonas Horner, senior Sudan analyst at the International Crisis Group. Some Israeli flights have already begun crossing Sudanese airspace.

Sudan this month also said it was settling a long-running civil court case centered around the 2000 bombing of the USS Cole, an American warship docked in the Yemen port of Aden. Seventeen sailors were killed and dozens of other people injured in the al-Qaeda attack that Bashir’s government was accused of supporting.

Family of the victims are set to be compensated in an undisclosed payout, though Sudan’s government stressed the deal didn’t mean it accepted responsibility and was agreed to speed the dropping of the U.S. terror designation. The Trump administration is now arguing that victims of the 1998 bombings of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania should be compensated by Sudan, which is accused of harboring the attacks’ plotters.

All this comes as Sudan’s economic turmoil continues. Annual inflation topped 64% in January, the pound has tumbled on the black market and lines for bread and fuel have returned in the capital. The European Union on Feb. 29 announced 100 million euros ($110 million) in aid for Sudan’s transitional government.

While the current terrorism designation may carry a risk for reputation that deters investors and banks from re-engaging, “Sudanese expectations around de-listing may be too high,” said Lauren Blanchard, an Africa analyst for the U.S. Congress.

“Concerns about corruption, outdated infrastructure and economic fragility may still deter investment for some time,” she said.

Salih, the minister, said it’s unfair to let the Sudanese people pay the price of the old regime twice.

“Once, when they directly suffered under Bashir, and now when we are still stuck with these sanctions and can’t integrate ourselves with the world,” he said.

To contact the reporters on this story: Mohammed Alamin in Khartoum at malamin1@bloomberg.net;Samuel Gebre in Addis Ababa at sgebre@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Benjamin Harvey at bharvey11@bloomberg.net, Michael Gunn, Karl Maier

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.