Elusive Economic Growth Points to Depth of Brazil’s Problems

Elusive Economic Growth Points to Depth of Brazil's Problems

(Bloomberg) -- President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration bets that overhaul of an unsustainable pension system will unlock Brazil’s economic potential, but sinking growth projections show the country has deeper-rooted problems.

The recovery is again disappointing despite a full year of record-low borrowing costs and a recent improvement in business confidence. Latin America’s largest economy grew a paltry 1.1 percent in 2017 and in 2018. On Thursday the central bank cut its 2019 growth forecast to only 2 percent, matching a dwindling consensus estimate. Economists started cutting their projections even before the most recent signs of trouble for pension reform.

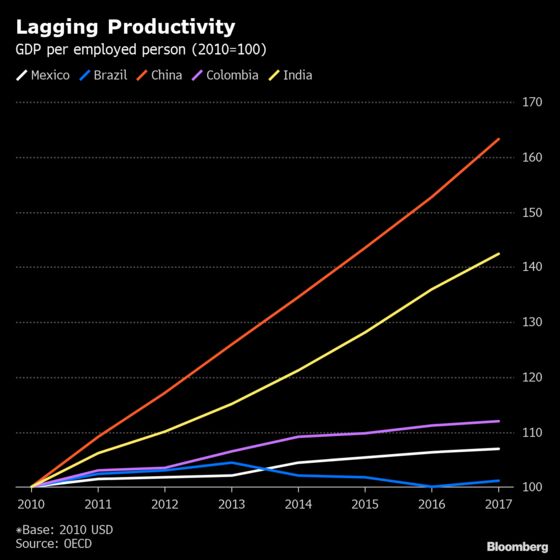

Structural issues that have hobbled Latin America’s largest economy for decades are rearing their heads. The malaise is chronic, because Brazil has barely improved a business environment that’s crippled by a mind-bending tax system, regulatory uncertainty, crumbling infrastructure and widespread inefficiency. With a commodity boom that had propelled growth long gone, there’s renewed urgency to get to the root of the country’s stagnation.

“I don’t see any significant investment happening. The country’s been stagnant since 2011 and lacks energy. Where’s the source of growth?’’ Marcos Lisboa, president of business school Insper, said in an interview. “We’re wasting our opportunities. Either we start changing the country, or our generation and the next will see it stuck in mediocrity.”

Pension reform, Bolsonaro’s flagship economic proposal, can prevent public finances from careening off a cliff but is no silver bullet. Instead, many companies see the bill as a test of the administration’s ability to improve the business climate, according to Carlos Sequeira, BTG Pactual’s head of equities research for Latin America.

Crumbling Infrastructure

Brazil’s woeful ports, roads and highways rank high among grievances. Four months ago, a major Sao Paulo overpass gave way, snarling traffic of the Southern Hemisphere’s biggest metropolis that already loses some 40 billion reais ($10.6 billion) annually to congestion, according to the FGV School of Economics.

Outside cities, potholes pock rural roads -- when they’re paved. The main northbound soy highway turned to mud in 2017 rains, trapping truckers in 42 kilometers of gridlock en route to port.

Over the past two years, Brazil made progress in reducing the time it takes to open a new business -- from 80 days to 21. That still compares to eight in Mexico and six in Chile, World Bank data show. When it comes to taxes, an average medium-sized company spends 1,958 hours completing its ten annual payments, double the time spent by the second-worst placed nation, according to the bank’s Doing Business survey.

What Bloomberg’s Economist Says

“Former President Michel Temer’s administration made some progress on the competitiveness agenda, but Brazil continues to struggle with bureaucracy, tax complexity, juridical uncertainty and low labor productivity. Minister Paulo Guedes and his team want to bring Brazil to the top 50 countries in terms of business environment by the end of this presidential mandate -- quite a feat considering the country currently ranks 109th in the World Bank’s Doing Business survey. If accomplished, this would definitely support an increase in productivity, allowing the country to enjoy stronger growth without inflation.”

-- Adriana Dupita, Latin America economist

Regulations dog small companies to powerhouses like Ford Motors, which has been in Brazil since Henry Ford built an industrial town deep in the Amazon jungle. Last month, labor leader Adauto de Oliveira met Ford’s South America president, ostensibly to discuss investments to extend a local plant’s lifespan. Instead, the executive announced he’d decided to shutter the facility, as regulatory expenses left Ford unable to make a profit in Brazil.

“It was a bucket of cold water,’’ said De Oliveira.

He barely had time to relay the news to co-workers before Ford released a statement. The company’s expected cost of closure: $460 million, mostly for severance.

Carwash Corruption

To be sure, Brazil’s problems are not as bad as in neighboring Argentina and not everyone is as pessimistic. Growth was in good measure supported by construction programs that were hurt when builders were implicated in the Carwash corruption probe, said Fabio Kanczuk, a former economic policy secretary, now a World Bank executive director. As those projects resume, he bets growth will accelerate to over 3 percent in the fourth quarter, compared to the prior year.

But Adolfo Sachsida, the government’s economic policy secretary, says that more will be needed to accelerate growth in a country beset by years of inaction.

“When people err for a long time, there’s a cost of correcting course,’’ he said. “It takes time and the confidence that the new model is here to stay.’’

To contact the reporters on this story: Rachel Gamarski in in Brasilia at rgamarski@bloomberg.net;Vinícius Andrade in São Paulo at vandrade3@bloomberg.net;David Biller in Rio de Janeiro at dbiller1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Daniel Cancel at dcancel@bloomberg.net, ;Raymond Colitt at rcolitt@bloomberg.net, Matthew Malinowski, Walter Brandimarte

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.