The Campaign Against Europe Just Got a Boost From Swedish Voters

The Campaign Against Europe Just Got a Boost From Swedish Voters

(Bloomberg) -- Sign up for the Brussels Edition, a daily email briefing on what matters most in the heart of the European Union.

Europe’s political outsiders chalked up another milestone in the Swedish election as a rise in support for nationalists showed the battle lines being drawn right across the continent.

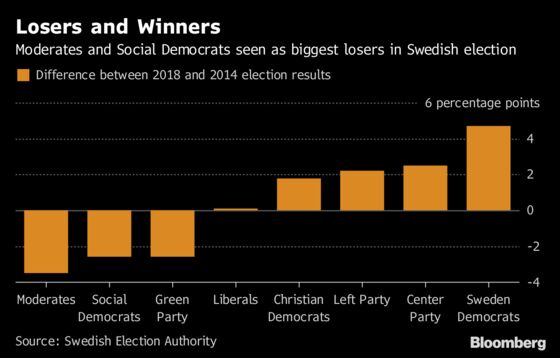

While the anti-immigration Sweden Democrats fell short of some pollsters’ projection, they still posted the biggest gains in Sunday’s vote -- in a country once seen as a bastion of liberalism. The uprising sweeping through Europe leaves the establishment in Stockholm hamstrung, just as it has done in Italy, the U.K., Poland and elsewhere. It shows little sign of abating.

“It’s populist, it’s insurgent, it’s a challenge to the status quo,” said Ian Lesser, senior director for foreign policy at the German Marshall Fund of the United States, a think tank based in Brussels. “It will remain a significant political force.”

Where once elections were fought between center-right and left, the pendulum swinging gently for decades between different degrees of state intervention and economic liberalism, now they pitch the established order against the disrupters. Their advances threaten some of the fundamental achievements of the 61-year European experiment.

The next upheaval could come in May, when the European Union holds elections to its parliament in all member states. With the balance of power in the bloc at stake, that vote could change the political landscape more dramatically than any since the Cold War.

The Sweden Democrats have their roots entwined with the country’s neo-Nazi movement and want to capitalize on the Brexit moment to follow the U.K. out of the EU. The party’s message is similar to the anti-establishment forces elsewhere, with a heady mixture of anti-immigration rhetoric, tirades against the elite and an evocation of better times past. Some flirt with Russia. Many ape Donald Trump.

Traditional politicians across the continent will recognize that script. Since the arrival of more than a million migrants from the Middle East and Africa in 2015, insurgents have realized there’s political capital to be gained by fueling voters’ fear of foreign arrivals.

In Italy, Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini has been setting the agenda for the populist coalition, dominating the debate by mixing attacks on immigration and EU economic policies. His latest target is the “left-wing’’ judges exploring criminal charges against him over his handling of migrants.

Targeting Macron

Salvini has forged the beginnings of an alliance with Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, another leader who has long defied Europe’s democratic norms. They are positioning themselves as leaders of a broad “illiberal’’ front, lined up against the EU elite.

They have allies in the Polish government as well as rising opposition groups like the National Front in France and Alternative for Germany, and in the Netherlands, Denmark and Finland. Few European countries are untouched.

Leading the defense of the European project is French President Emmanuel Macron, who has clashed repeatedly with Salvini since the Italian coalition came together.

“If they want to see me as their main opponent, they are right,’’ Macron said last month.

Macron’s two-year-old party, The Republic on the Move, has held talks in recent months exploring the possibility of joining forces with several like-minded European parties, including the liberal ALDE group, which has eight prime ministers across the EU.

He’ll not only be up against the nationalist Europeans but also Steve Bannon, an architect of Trump’s election victory and his White House strategist until a year ago, who has set up an organization in Europe to rally anti-EU forces.

“Sweden is another cautionary tale,” said Pawel Zerka, a Paris-based political scientist at the European Council on Foreign Relations policy group. “It is something that Salvini or Orban can use to say ‘look, the mainstream parties simply don’t listen.’ ”

--With assistance from Helene Fouquet, Jonathan Stearns and Rafaela Lindeberg.

To contact the reporter on this story: Ian Wishart in Brussels at iwishart@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Alan Crawford at acrawford6@bloomberg.net, Ben Sills, V. Ramakrishnan

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.