As NYC Public Housing Tenants Suffer, a Glimmer of Hope Emerges

As NYC Public Housing Tenants Suffer, a Glimmer of Hope Emerges

(Bloomberg) -- Lolita Miller had it all: mold, vermin, crime, stalled elevators, uncollected trash and winter days without heat or hot water.

After almost half a century living in New York’s public housing, she’d come to expect the neglect and squalor in Far Rockaway’s Bayside homes. So did most of the 400,000 residents in projects owned by the money-starved New York City Housing Authority.

Yet a federal program changing how rents get paid has allowed developers at Bayside to tap into $560 million in private and government funds. The difference: Investors can count on revenue from monthly vouchers guaranteed for 40 years, instead of the uncertainty of annual federal budget appropriations. That was enough to transform life throughout the 33-acre, 1,395-unit campus in Queens.

“It’s become a paradise,” Miller, 73, said as she stood in her kitchen, with its new stainless steel appliances and synthetic granite-lookalike counters. The makeover included a new bathroom, floors, windows and hot-water radiators. “It’s the essence of calling where I live a home. I sleep so peacefully now.”

Housing Crisis

Bayside’s reclamation stands out as a small yet significant success in the city’s crisis-ridden housing authority. A federal court has ordered appointment of a monitor after officials admitted they falsely certified lead inspections that were never made, and last month interim Housing Authority Chairman Stanley Brezenoff said the agency is still trying to determine whether it’s violating other regulations.

In an era of shrinking federal funds for public housing, the U.S. Housing and Urban Development program known as “RAD” -- Rental Assistance Demonstration -- has rare bipartisan support. Republicans back it because it’s revenue neutral: Money to cover the so-called Section 8 rent vouchers comes out of funds appropriated to pay traditional municipal housing authority subsidies.

While tenants continue to pay 30 percent of their income in rent, developers may use the more predictable revenue stream to obtain bank loans and attract investors who are seeking low-income housing tax credits or depreciation allowances. In the case of Bayside, the financing also included millions of dollars in state housing bonds and a one-time FEMA flood-protection grant. (Hurricane Sandy damaged the complex in 2012.)

The program began in 2012 as a small pilot. By 2017, Congress had made 225,000 units eligible for such financing, and this year it lifted the cap to 455,000. So far, 98,000 of the nation’s 1.15 million federal housing units are being renovated under the program.

New York follows hundreds of public housing authorities, from Fresno, California, to Baltimore, that have used the program to raise about $5.7 billion in private investment and grants, said Christopher Knight, spokesman for U.S. Senator Susan Collins, the Maine Republican who has pushed to expand the program as chair of the transportation and housing subcommittee.

Bayside is the first NYCHA development to get RAD funding. Under the program, the complex got new roofs, heating and electric systems as well as back-up generators and flood walls to protect its landscaped grounds.

New surveillance cameras, outdoor lighting, electronic locks and a private security consultant also have made a difference, said Joseph Camerata, vice president of Wavecrest Management Team Ltd., which co-developed the project with MDG Design + Construction. Bayside had zero crimes reported through July 22, compared with 23 felonies in the first six months of 2017, according to New York Police Department statistics.

The city also has won HUD approval to use RAD financing for projects in the Bronx and Brooklyn, which would bring the total to 15,000 units, or 8 percent of New York’s public housing portfolio -- enough to house about 45,000 people.

“We are going to be aggressive in trying to increase the number of RAD projects,” NYCHA’s Brezenoff said, though he added that he doesn’t know how many more developments could be eligible.

‘Not a Panacea’

Despite its initial success in New York, the program has its limits. Last year’s tax cuts could make low-income housing tax credits less attractive to investors. And NYCHA’s sheer size makes it impossible for most developers to arrange the millions of dollars in public and private investment needed to transform complexes. Nationally, the program might work for half of the remaining 1 million units, which are almost always in smaller developments and don’t require financing on New York’s scale, said Thomas Davis, director of HUD’s Office of Recapitalization.

“RAD is not a panacea,” Davis said. “If your rent revenue through Section 8 can’t pay off what the developer borrowed for renovation, and you can’t make up the difference with government or philanthropic grants or investors seeking tax credits and depreciation -- if the numbers don’t pencil out, you don’t have a viable transaction.”

The program hasn’t been problem-free. In Baltimore, developers have been accused of denying tenants access to grievance procedures, and of displacing or threatening them with eviction in Hopewell, Virginia, said Jessica Cassella, a staff attorney for the National Housing Law Project in Washington. Success depends on ensuring tenants know their rights, and active government oversight of living conditions, she said. At Bayside, NYCHA retains ownership of the land and operational oversight.

In New York, many of the housing authority’s 325 developments have deteriorated beyond the point where tax-credited investment and tax-exempt borrowing could make the financing work.

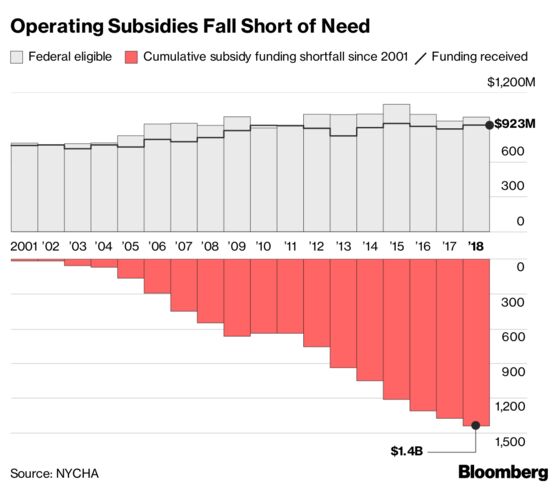

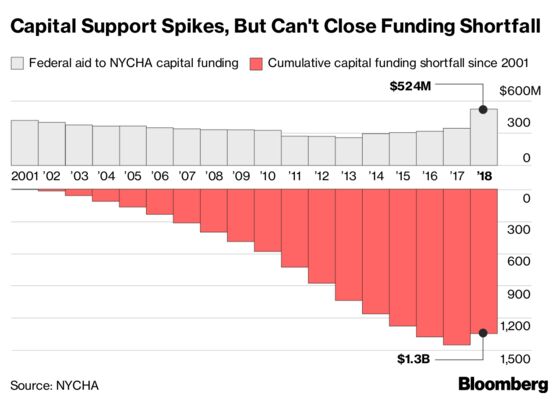

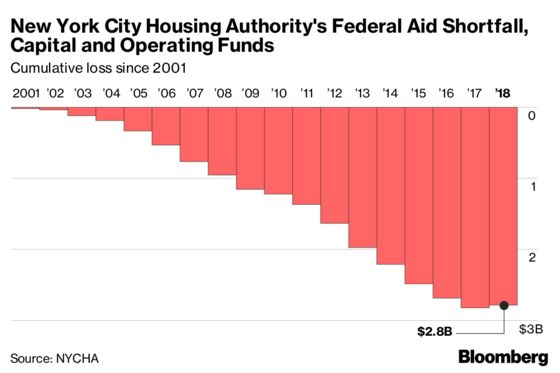

Years of deferred maintenance have eroded NYCHA’s credibility with tenants whose support for such conversions is crucial. Since 2001, federal operating support and capital spending for NYCHA has been reduced by a total of $2.8 billion, according to city records.

Boiler breakdowns last winter deprived more than 300,000 residents of heat and hot water. City Comptroller Scott Stringer reported in July a repair backlog of 55,000 jobs, with safety violations taking an average of 370 days to fix. After finding conditions throughout the system deplorable, a federal judge has ordered a monitor to oversee operations. It’s a political embarrassment for Mayor Bill de Blasio, who won election in 2013 decrying economic inequality by describing New York as a “tale of two cities.”

A visit to Bayside’s twin development across the street, the 418-unit Oceanside, illustrates some of the program’s pitfalls. The cost of renovation coupled with tenant distrust toward privatized ownership and management made a similar transaction unworkable.

“Resistance was across the board,” said Polina Bakhteiarov, NYCHA’s director for real estate development, describing the reaction at Oceanside when city officials first approached its tenants about a RAD conversion. The deal killer, she said, was that “the costs were too great. It was already the largest conversion in the program’s history.”

At Bayside, Lolita Miller says the changes have returned life to how it was when she moved in 48 years ago and the city’s public housing enjoyed a good reputation. Over the decades, mayors came and went as conditions kept getting worse, until Hurricane Sandy made living there a nightmare of mildew, mold, trash-strewn staircases and stench.

“It was a place everybody wanted to get out of but couldn’t,” she said. “Things kept happening and nothing got fixed. Now you just put a ticket in if you have a problem, and management takes care of it. I hear the gardeners outside. They’re planting bushes and trees.”

--With assistance from Erik Wasson and Jeremy Lin.

To contact the reporter on this story: Henry Goldman in New York at hgoldman@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Flynn McRoberts at fmcroberts1@bloomberg.net, Stacie Sherman

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.