Here Are the Latest Developments in Paul Manafort’s Trial

Manafort Fraud Trial Starts With Judge Questioning Potential Jurors

(Bloomberg) -- A federal jury in Alexandria, Virginia, has begun hearing the first case in U.S. Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s probe of Russian interference in the 2016 election. President Donald Trump’s former campaign Chairman Paul Manafort is on trial facing tax- and bank-fraud charges. If convicted, he could spend the rest of his life in prison.

Here are the latest developments:

The First Witness (6:00 p.m.)

Tad Devine, the Democratic political consultant who helped guide Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign in 2016, is the first witness for the prosecution in Manafort’s trial. Devine said he began working with Manafort in 2005 in Ukraine for the pro-Russia Party of Regions, and they ran campaigns there until 2010. Devine returned for a project in 2014, he said.

Devine said he was impressed with the work that Manafort did for the Party of Regions and Viktor Yanukovych, who was elected president in 2010 after overcoming low public-opinion polls.

“My impression was that it was a really incredible operation,” Devine told jurors. “I was deeply impressed by him and the people around him.”

Manafort and Yanukovych had a “very close relationship,” Devine said. Manafort “dealt with him directly.”

Devine also worked closely with Manafort’s translator, Konstantin Kilimnik. “We called him KK,” Devine testified. In February, Mueller got an indictment accusing Kilimnik of working with Manafort to try to tamper with witnesses. Prosecutors say Kilimnik has ties to Russian intelligence.

Prosecutor Greg Andres asked Devine about the financial backing of the Party of Regions. He said Ukrainian billionaire Rinat Akhmetov “was someone who contributed a lot of money to the party.” When Devine referred to Akhmetov as an oligarch, Andres asked him what that meant. “Someone of enormous wealth in Ukraine,” Devine responded.

Andres asked about Manafort’s relationship with Akhmetov. “I believe they knew each other well and spoke to one another,” Devine said.

The Case for the Defense (4:23 p.m.)

Defense attorney Thomas Zehnle used his opening statement to place blame squarely on Rick Gates, Manafort’s former right-hand man who pleaded guilty and is cooperating with prosecutors.

Manafort is a talented political consultant who advised U.S. presidential candidates, congressmen and senators for almost 40 years, while also working with foreign leaders and heads of parliament in other countries, Zehnle said. He trusted people who worked for him to fill out his tax returns and bank loan applications correctly, particularly Gates, he said.

“This case is about trust, and he placed his trust in the wrong person -- Rick Gates,’’ Zehnle said. “We’re purely here because of one man -- Rick Gates. The foundation of the special counsel’s case rests squarely on the shoulders of this star witness,’’ who pleaded guilty and is cooperating with Mueller.

Manafort “could not be everywhere at once,’’ so he relied on Gates to fill operational and financial roles and to serve as the main contact to back-office employees, Zehnle said.

Despite Manafort’s trust in him, Gates “embezzled millions of dollars from his employer.’’ He proceeded to file amended tax returns that were false, and he told evolving stories to prosecutors that also were untrue, Zehnle said.

“Rick Gates violated one of life’s most basic principles -- when you’re in a hole, stop digging,’’ the lawyer told jurors.

Manafort used accounts set up in Cyprus not to cheat on U.S. taxes but because the wealthy financial backers of Ukraine’s Party of Regions insisted on it, Zehnle said.

“Paul Manafort did not create this arrangement, and he was certainly not trying to mislead or deceive the Internal Revenue Service,’’ he said.

Zehnle also said that Manafort met in July 2014 with FBI agents who were looking into potential misuse of money by Ukrainian leaders. Manafort told agents that he’d earned about $27 million in Ukraine in the years that agents asked about, that he sent money to Cyprus accounts and that his Party of Regions backers preferred that, Zehnle said. He also gave agents the names of accounts that prosecutors said he hid from U.S. authorities, the lawyer said.

Jury Hears Prosecution’s Case (3:25 p.m.)

Manafort hid millions of dollars from his consulting businesses offshore to avoid U.S. taxes and secretly funneled the money into the country to finance his lavish lifestyle that included luxury homes, fancy cars and pricey suits, a prosecutor told the jury at the start of the trial.

"A man in this courtroom believed the law did not apply to him,” were the first words to come out of the mouth of Assistant U.S. Attorney Uzo Asonye as the trial started.

Asonye told the jury that Manafort collected more than $60 million while working for Ukraine and used shell companies and offshore bank accounts to funnel millions of dollars into the U.S.

“He got whatever he wanted,” Asonye said. One thing he didn’t do that millions of Americans do every year is "pay the taxes he owed,” he said.

At one point the judge admonished Asonye to focus on the elements of the crime, which he said he would.

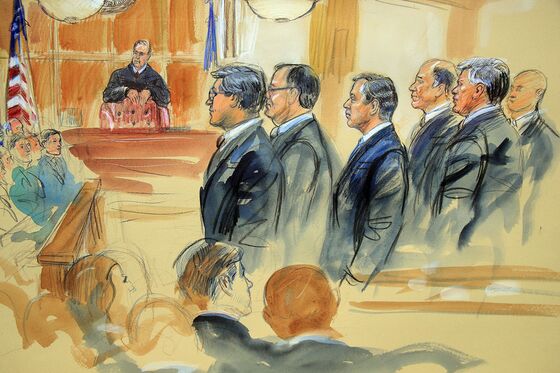

Jury Sworn In (1:58 p.m.)

A jury of six men and six women were selected and sworn in to consider the tax- and bank-fraud charges againstManafort.

Jurors will hear opening statements on Tuesday afternoon in federal court in Alexandria, Virginia. U.S. District Judge T.S. Ellis III pushed the lawyers to move rapidly to select a group of 12 jurors and four alternatives who said they could judge Manafort in a fair and unbiased manner.

Virtually no biographical information about the jurors was disclosed, by the judge’s design.

Manafort faces an 18-count indictment charging him with filing false tax returns, conspiracy to commit bank fraud and failing to file reports of his foreign bank accounts with the U.S.

Prosecutors say Manafort made more than $60 million as a political consultant in Ukraine, that he failed to report a “significant percentage” of it on his tax returns, and that he lied to lenders who gave him $20 million in loans.

He faces a separate trial in Washington on charges of money laundering, acting as an unregistered agent of Ukraine, and obstruction of justice.

On Tuesday, Ellis identified for the first time the four lenders that prosecutors say Manafort defrauded. They are Genesis Capital, Citizens Bank, Bank of California and Federal Savings Bank in Chicago, where Steve Calk is the chief executive officer.

Calk was part of the Trump campaign’s economic advisory panel. House Democrats have questioned whether Manafort received the loans in exchange for promises to Calk of a high-level job in the Trump administration.

During jury selection, Manafort, dressed in a dark suit and a white shirt, sat with his lawyers. His wife, Kathleen, attended the proceedings.

The Manafort cases are U.S. v. Manafort, 17-cr-201, U.S. District Court, District of Columbia (Washington), and 18-cr-83, U.S. District Court, Eastern District of Virginia (Alexandria).

More:

To contact the reporters on this story: David Voreacos in federal court in Newark, New Jersey, at dvoreacos@bloomberg.net;Andrew Harris in Washington at aharris16@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Jeffrey D Grocott at jgrocott2@bloomberg.net, Joe Schneider, David S. Joachim

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.