(Bloomberg Opinion) -- “Italy’s fate does not lie in the hands of financial markets,” European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said this week. The bond vigilantes might have something to say about that.

When Italy adopted the single European currency at the start of 1999, it did so at a rate of 1,936 lire to the euro. So here’s a thought experiment: If the incoming government were to abandon the euro and reintroduce the lira at that value, where would it trade the following day? And just how high would the nation’s cost of borrowing for 10 years, currently about 2.8 percent, end up rising to?

The financial carnage following a redenomination of Italy’s substantial debts would dwarf any crisis the euro zone has endured. After Greece peered into the abyss of breaking with the euro and turned back, I’d be amazed if any politician would seriously contemplate leading Italy into the economic wilderness.

The prospect of a populist government that seems lukewarm at best to Italy remaining in the euro has prompted investors to drive up the nation’s borrowing costs. Given that the country owes its bondholders 2 trillion euros ($2.3 trillion) — rising to 2.4 trillion euros once interest costs are included — the fund management community has rather a lot of muscle it can employ to keep a profligate administration in check, especially given the European Central Bank’s reluctance to be seen dabbling in matters it deems political, even though it’s owed more than 340 billion euros by the sovereign.

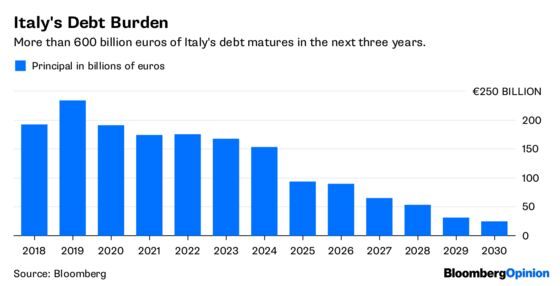

Moreover, 600 billion euros of Italy’s debts fall due before the end of 2020. The results of this week’s auction, which saw the yield investors demand to buy five-year paper surge above 2.3 percent — four times more than what they were willing to accept on the securities at an April sale — are a harbinger of what might be to come as those maturing bonds need to be rolled over in the next few years.

Investors aren’t really expressing fears that Italy will appoint a finance minister with a secret plan B to overthrow the euro, or that the Five Star Movement and the League will carry out their initial plan to seek a debt write-off. If that were the case, the country’s two-year yield would be well north of the 1.5 percent level it currently trades near.

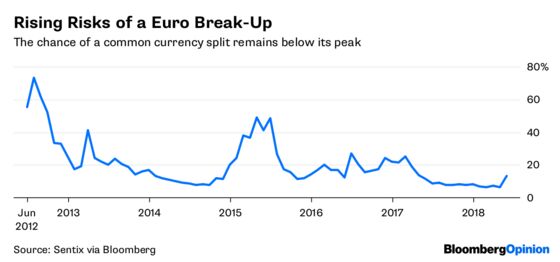

While the Sentix Euro Break-Up Index, a monthly gauge of investor concern about the threat, has jumped to its highest in a year, it remains well below the levels recorded during the sovereign debt crisis in 2012 or in 2015, when Greece was on the brink of dropping out.

Bondholders are more concerned that the next administration will embark on a spending free-for-all that will drive Italy’s debt-to-gross-domestic-product ratio well above its already elevated level of 130 percent. And it’s here that the financial markets can, and will, express influence over Italy’s fate, albeit of the economic rather than political flavor.

The term “bond vigilantes” was coined in the early 1980s by economist Ed Yardeni — and the posse has a track record of holding governments accountable for their economic policies.

In the early 1990s, Sweden’s government was forced to cut spending as investors drove up government borrowing costs in response to a budget deficit of 13 percent. And in the U.K. in June 2010, newly appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne was less than a minute into his first budget speech before he addressed gilt investors directly, saying concerns about the liquidity and solvency of the government were questions he didn’t want “ever to be asked of this country” as he embarked on an economic austerity program.

And it was the bond vigilantes driving up yield premiums in the euro zone that prompted ECB President Mario Draghi’s 2012 pledge to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro.

Voters have the right to elect whatever shade of government they desire and, as my Bloomberg Opinion colleague Ferdinando Giugliano has argued, the Five Star Movement and the League have a legitimate right to govern.

But Italy’s lenders also have a legitimate say in how the nation comports itself economically — and they get to vote even more frequently than the electorate.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Edward Evans at eevans3@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.