The Most Radical Economic Plan in Years, and Now It's Mainstream

What kind of jobs do fully-employed Americans have? And who’s left out of that picture?

(Bloomberg) -- Every American who wants a job has one.

That’s the street-level understanding of “full employment.” With a jobless rate that fell to 3.9 percent last month, many economists -- including policy makers at the Federal Reserve -- say the U.S. is basically there.

On the surface, it’s an odd time to turn the government into an employer of last resort, hiring anyone who wants to work. But that’s what many Democrats are proposing, and not just on the party’s left. Could-be presidential candidates, including senators Cory Booker of New Jersey and Kirsten Gillibrand of New York, are lining up behind versions of a jobs guarantee that may rank among the most radical economic plans debated in Congress for decades.

It would also be among the most expensive and disruptive, particularly for business -- part of the reason why the various draft bills likely won’t pass the current Congress and may struggle in future ones. Still, if politicians are betting that the once-fringe idea has traction, it’s because of doubts that underlie the upbeat labor-market headlines. What kind of jobs do fully-employed Americans have? And who’s left out of that picture?

‘Precarious, Low-Paid’

At the heart of the first question are issues of security, conditions and pay.

“We have had a growth in employment, but we have not had a growth in employment of decent jobs,” said William Darity, an economics professor at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, who’s contributed to job-guarantee proposals. “That’s the big issue. People have precarious work, low-paid work, no benefits or few benefits.”

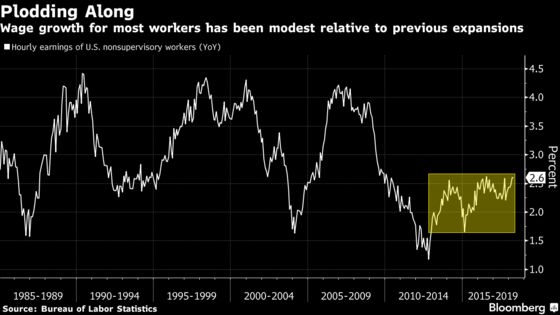

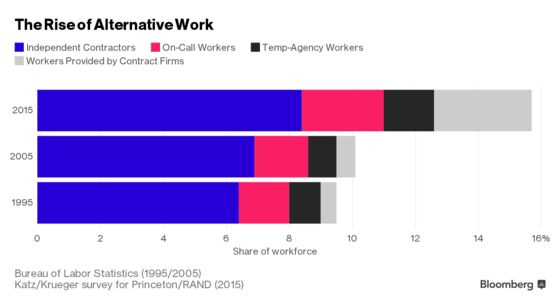

In America’s recovery from the 2008 crisis, growth has skewed toward the wealthy. Wages have grown slowly by past standards, especially for low-paid workers. Jobs are also becoming less secure. A landmark study by Princeton’s Alan Krueger and Harvard’s Lawrence Katz found that all the net positions created in the decade through 2015 fell into the category broadly labeled the gig economy: contract-based, on-call, outsourced.

There are also 5 million part-timers who’d like to be full-time; 2.8 million people who lost a job last month or were on a temporary contract that ended; and 1.4 million who are looking for openings sporadically or have given up. The share of the working-age population that’s actually in work hasn’t recovered to the level it reached before the Great Recession, let alone its 2000 peak. Kevin Hassett, chairman of President Donald Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers, said in November that in some circumstances, more government hiring could help.

‘Fantasy-Land’

The most detailed version of the jobs guarantee aims to draw all those people back in. It’s been developed over the years by a group of unorthodox economists who call their school of thought Modern Monetary Theory, and argue that there’s more room for deficit spending than is widely believed.

Their plan, a blueprint for a proposal that Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders is crafting, would offer work nationwide at $15 an hour, more than double the federal minimum wage. Funding would come from the federal government, but jobs would be assigned locally. There’d be a part-time option, and benefits including health care.

The net cost would be between $200 billion and $400 billion a year, the authors estimate. That’s roughly in the ballpark of federal spending on Medicaid, and would expand an already-widening budget deficit by as much as 2 percent of GDP.

The fiscal hit is just one reason many economists find the plan implausible. Brian Riedl of the conservative Manhattan Institute dismisses a jobs guarantee as “fantasy-land economics.” He said it would require higher taxes, and devastate industries like retail and fast food which pay below the proposed rate.

There are practical questions -- how to find useful work for millions of workers -- and philosophical ones about the government’s role in the economy.

‘Usurping the Market’

“It’s the sort of thing that sounds good on the surface, but the more they dig into it, they say how’s this going to work?” said Stephen Stanley, chief economist at Amherst Pierpont Securities and a former Federal Reserve researcher. “It’s usurping the market.”

Stanley notes that the last time America attempted anything similar was during a real labor emergency: the Great Depression. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration hired millions of workers across the U.S., largely for construction jobs.

New Deal programs fell short of a full federal jobs guarantee, and so do some of the current proposals. Booker is introducing legislation to test the idea in 15 communities. That’s not how the most important safety-net programs such as Social Security and Medicaid were born, points out Stephanie Kelton, a leading MMT economist. She was an adviser to Sanders in 2016, and has been working with him recently on a national jobs guarantee proposal.

‘Jobs, jobs, jobs’

There are House primary candidates running on the idea this year, including Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in New York, Randy Bryce in Wisconsin and Dan Canon in Indiana. Massachusetts Senator Elizabeth Warren, a potential presidential nominee, has expressed support.

In November’s congressional mid-terms and likely in 2020, Democratic candidates will come up against Republicans campaigning on the successes of the Trump labor market. As the unemployment rate edged lower on his watch, the president has celebrated on Twitter. “Jobs, jobs, jobs” is a favorite refrain.

But unemployment was already under 5 percent, at the low end of recent norms, in November 2016 when Americans threw out the incumbent party and elected Trump. And in 2006, when the jobless rate was even lower, voters swept Republicans out of their congressional majority.

“The lesson from 2016 is that many Americans were left out of this economy, and particularly in places that have concentrated unemployment and a lack of resources,” California representative Ro Khanna said by phone. He’s working on his own jobs-guarantee bill, and says he hopes the idea will “become a serious part” of the Democratic platform.

Hardly Satisfied

Polling on the issue is sparse. Three-quarters of Americans worry about federal spending and increased deficits, according to Gallup. But Civis Analytics, a data firm founded by an aide to former President Barack Obama, found that more than half of Americans think the government should provide employment for those who can’t find it.

Support was highest among the young, the poor, and people of color. Jobless rates among minorities have reached record lows; still, black unemployment is nearly double the national level, and for Hispanic Americans it has averaged 6.5 percent over the last five years.

And even among those with jobs, “we have high rates of working poverty,” Duke’s Darity said. “We should hardly be satisfied.”

--With assistance from Sahil Kapur and Jordan Yadoo.

To contact the reporter on this story: Katia Dmitrieva in Washington at edmitrieva1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Scott Lanman at slanman@bloomberg.net, Ben Holland, Sarah McGregor

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.