China Could Outrun the U.S. Next Year. Or Never

Extrapolating when the world’s second-biggest economy will overtake the first is a tricky business riddled with caveats.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Remember when Japan was going to become the world’s biggest economy?

Don’t laugh. Herman Kahn, the Rand Corp. futurist who partly inspired the character of Dr. Strangelove, predicted as far back as 1970 that Japan’s gross domestic product would overtake the U.S. around the year 2000.

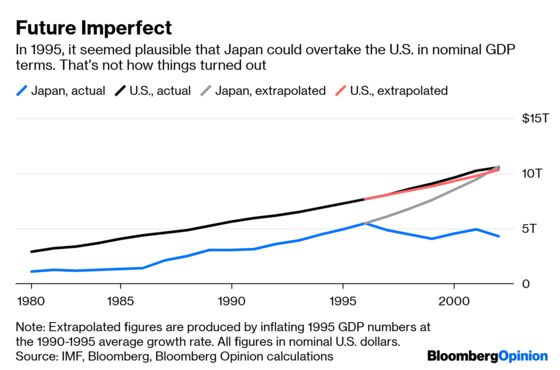

Decades later, his prediction still seemed on track. Thanks in part to the strength of the yen, Japan was just months away from matching the U.S. in GDP terms, one 1995 Los Angeles Times article predicted. Halfway through that country’s lost decade, it’s hard to believe that this wasn’t a fringe view – but it was nonetheless the subject of an essay in the august Foreign Policy magazine and a well-received accompanying book.

If you extrapolated early-1990s growth rates on a chart, indeed, the forecast seemed almost irrefutable – but that’s ultimately a lesson about the hazards of extrapolating lines on charts.

As my colleague Daniel Moss has argued, we should heed that mistake every time we predict that China is on the brink of a similar coup.

China’s official figures for the size of its economy are about 16 percent larger than they should be, and measures of real GDP growth were overstated by about 2 percentage points between 2008 and 2016, according to a study published by the Brookings Institution Thursday. Combined with the country’s own downgrade of its GDP growth for this year to a range of between 6 percent and 6.5 percent earlier in the week, that represents a sort of profit warning for the economy.

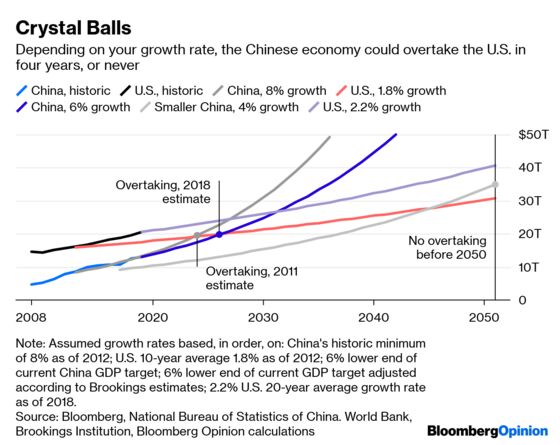

It’s worth reflecting that this particular stock has already had its share of analyst downgrades. Back in 2010, Standard Chartered Plc was predicting that China’s economy would overtake the U.S. by 2020, and would be nearly twice the size by 2030. Four years later, IHS Markit Economics forecast the tipping point would come the same 10 years into the future, in 2024.

Those forecasts seem fanciful in the light of the way China’s economy has slowed – and America’s has accelerated – during the era of President Xi Jinping. At market exchange rates and current prices, U.S. GDP was $20.54 trillion in 2018, about 60 percent larger than China’s $13.09 trillion.

That just shows how misleading extrapolations can be. If you had inflated China’s 2011 GDP at the 8 percent rate then considered the minimum politically tolerable, and grew America’s at its then-10 year average of 1.8 percent, you’d have put the tipping point around 2023. Do the same forecast now with China’s growth at the 6-percent end of the official forecast band, and the U.S. would still be seen falling behind in 2028, roughly in line with Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s Jim O’Neill’s longtime forecast.

What happens, though, if we see the U.S. growing from here at its 20-year average rate of 2.2 percent, and apply Brookings’ adjustments to China’s current GDP and growth-rate forecasts? In that eventuality, China’s GDP continues to trail the U.S. all the way out to 2050.

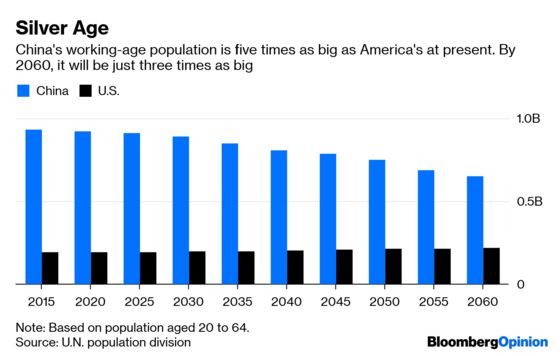

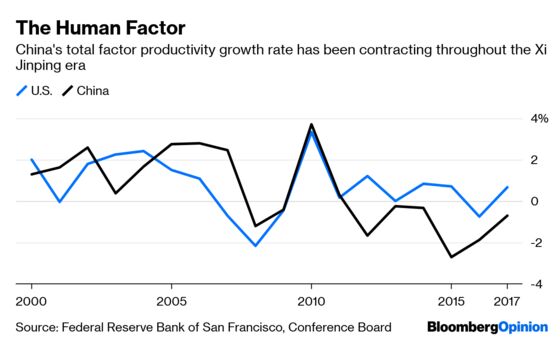

By that time, demographic factors will be weighing heavily against catch-up growth. China’s workforce, nearly five times the size of America’s at present, will only be a bit more than three times as large, meaning total factor productivity will have to be growing still faster to close the gap – and all the evidence is that, to the contrary, it’s been contracting.

That’s not a reason to count China out. For one thing, as my colleague Noah Smith has written, it’s already the larger economy according to purchasing-power parity (a way of adjusting for the fact that the same income buys a higher standard of living in China).

For another, such measures are heavily influenced by exchange rates, one reason Japan seemed so mighty when the yen was nearing 80 cents in the mid-1990s. On top of that, as Bloomberg Intelligence economist Tom Orlik argued Friday, China’s official GDP numbers may be more robust these days than Brookings is giving them credit for.

Most importantly, though, it’s a lesson that numbers like these aren’t really a solid-enough foundation for building such grand strategic narratives, however tempting it is to do so. Even at its current scale, China is a scant 15 percent of the global economy, and it’s unlikely to crack more than 20 percent at market exchange rates in the foreseeable future.

Fretting over adjustments to long-run economic forecasts is really just a proxy for our deeper anxieties about the fracturing of democracy in Western countries and the growing confidence of authoritarian governments from Beijing and Brasilia to Moscow and Ankara. If we want to ensure the international liberal order survives another century, we’d do much better to focus on those real problems in the present, rather than fixate on the impending doom of an imagined future.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.