What Uber Left Behind in Asia

Emerging markets outshine the U.S. in ride-hailing, as the burgeoning success of Go-Jek and Grab shows.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- All it takes is a quick trip to Jakarta to realize that Uber Technologies Inc. missed out on the opportunity of a lifetime.

Go-Jek Indonesia PT and GrabTaxi Holdings Pte, which started out as copycats of the U.S. ride-hailing pioneer, have morphed into something far grander. Not only are their main car-hire businesses thriving, the companies have turned into super-apps that can satisfy a range of personal needs, from paying bills and ordering food to finding house cleaners. That’s helped make them Southeast Asia’s two most valuable unicorns.

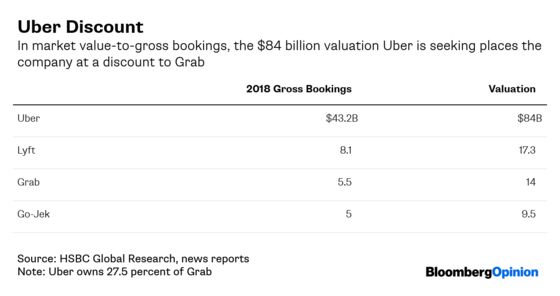

As Uber seeks an $84 billion valuation in what’s expected to be the year’s biggest U.S. IPO, it’s a reminder that the company turned its back on a gold mine when it sold its Southeast Asian operations to Grab last year. Compared with the U.S., emerging markets have far greater potential for ride-hailing.

To fathom the supply and demand dynamics, we can ask two broad questions. First, does the app pay well enough to attract drivers? Second, does it make sense to use ride-hailing services rather than owning a car, or taking other forms of transportation?

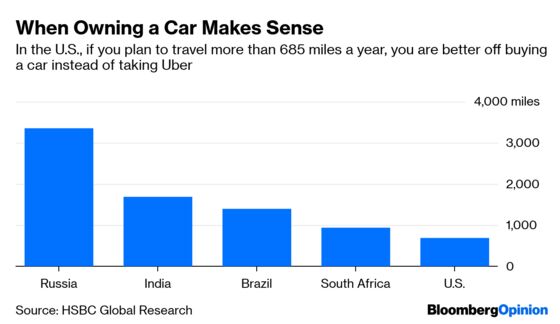

The U.S. scores poorly on both accounts. Net of expenses, drivers earn on average $12 per hour in the U.S., about two-thirds more than the federal minimum wage of $7.25, HSBC Holdings Plc estimates. The ratio in developing countries is multiples of the minimum wage. Meanwhile, if you intend to travel more than 685 miles (1,100 kilometers) a year in the U.S., you’re better off buying a car.

The Indonesian capital passes both tests with flying colors. Thanks to ride-hailing apps, millions are entering the labor force for the first time. A recent survey cited in the Jakarta Post shows that roughly a third of drivers hired by Go-Jek and Grab had no income prior to joining.

On the demand side, only the wealthy can afford a car in Indonesia, a nation where few have access to consumer credit and household debt is only 10 percent of GDP. Meanwhile, Jakarta’s first mass rapid transit system, which started in March, isn’t extensive enough to service a metropolis of 10 million people.

For investors, the nightmare prospect is that ride-hailing apps slip into the classic Prisoner’s dilemma, engaging in a race to the bottom that kills profit margins. In the U.S., there’s little to stop Uber from trying to nudge out Lyft Inc., its smaller competitor — even though it might be more profitable for both to share their duopoly. It isn’t hard to lure customers away: Passengers can easily compare prices on their smartphones, while there’s nothing to stop drivers from registering with multiple apps.

Super-apps make drivers stick without the need for subsidies. Done with your rush-hour ride? No problem, it’s approaching lunchtime and drivers can work on restaurant deliveries through the app. In the afternoon, they can deliver groceries, and then the evening commute is around the corner. Reward programs are also helping to build customer loyalty. Grab, for instance, now offers points for spending on its app. Indonesians can redeem them for miles on flagship carrier Garuda Indonesia, cash vouchers at KFC or ice cream from Cold Stone Creamery.

Go-Jek has brought down driver incentives in Singapore significantly, dashing users’ hopes of a price war after the Indonesian firm entered the home market of Grab in December. In December, a Go-Jek driver could make S$2,400 ($1,7863) for 120 trips; by March, that had fallen 22 percent to S$1,865, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

The rivals are too busy spending on their super-apps to bother with raw cash subsidies. User acquisition costs are lower for each incremental function added, the thinking goes. As a result, Go-Jek and Grab have turned acquisitive, buying up smaller startups that can enhance their apps.

There may be more to come. Mobile payments pioneered by Go-Jek are already ubiquitous in Jakarta, creating another potential giant in the mold of Ant Financial, the affiliate of Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. The firms are also tiptoeing into online consumer lending. Grab’s new “pay later” feature functions like an online credit card: That could do well in a nation where the plastic penetration rate is only 2 percent.

It’s hard to see a similar game changer for Uber or Lyft. Americans do their shopping on Amazon.com. Autonomous vehicles seem to be the main hope, with the words showing up close to 100 times in Uber’s IPO prospectus. Driver earnings account for as much as 40 percent of gross bookings for the U.S. firms. The question is whether consumers are ready to sit in driverless cars yet. The Asian unicorns look to have a more viable path to higher earnings.

Uber said leaving Southeast Asia would allow the company to double down on plans for growth. In reality, it may have left its best growth prospect sitting on the sidewalk in Jakarta.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Matthew Brooker at mbrooker1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.