Warren Buffett Distracts From 'Mind-Numbing' Earnings

Don’t “obsess on the details” of Berkshire Hathaway’s results, the Oracle of Omaha says. Investors smile and nod.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- As a larger-than-life CEO, Warren Buffett tends to overshadow anything happening within his $500 billion conglomerate, Berkshire Hathaway Inc. Case in point: An entirely inconsequential charity lunch that’s been canceled between the billionaire and a Chinese cryptocurrency entrepreneur has gotten far more attention than today’s quarterly earnings report from Berkshire will.

It’s easy to lose sight of the fact that Berkshire Hathaway is the most valuable company in the world outside of the technology industry, an outlier in a ranking that goes like this: Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Alphabet, Facebook, Berkshire. Only five members of the S&P 500 index generate more free cash flow than Berkshire does. The company is run by 88-year-old Buffett and his 95-year-old business partner, Charlie Munger, who is just barely the oldest member of Berkshire’s aging board of directors. And though there are successors waiting in the wings, they simply won’t have the same prestige or credibility with shareholders. Even when one of the company’s other investment managers purchased a more than $800 million stake in Amazon.com Inc. earlier this year, investors wanted to hear about it from Buffett himself.

There’s constant speculation about the future of Berkshire, including what giant companies Buffett may acquire next and whether it will be his final megadeal. The company is sitting on a record $122 billion of cash. But for now, let’s check in with the hodgepodge of businesses Berkshire already has, the health of which makes Buffett’s dealmaking possible. They earned a combined $6.14 billion in operating earnings in the latest period, down 11% from a year ago, as insurance underwriting income dropped.

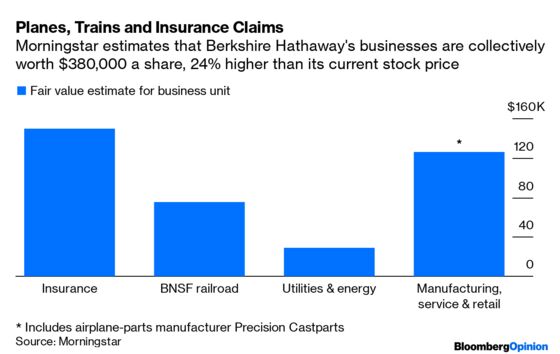

Berkshire’s insurance division is the most integral part of the conglomerate because Buffett can invest the premiums, earning a return before they get paid out to policyholders. In 2017, a surge in claims tied to natural disasters such as Hurricane Harvey resulted in Berkshire’s worst underwriting loss in 15 years. The business is back to turning an underwriting profit, though the $353 million it took in last quarter is down a bit from the nearly $1 billion it earned a year ago. Still, the unit’s investment income climbed 20% to $1.37 billion. Gregg Warren, an analyst for Morningstar Inc., pegs the fair value of the entire insurance division at $149,900 a share. That makes up the largest portion of his $380,000 sum-of-the-parts estimate for Berkshire stock:

One of Berkshire’s most well-known insurance brands is Geico, whose longtime CEO Tony Nicely retired a year ago. Buffett honored Nicely in his annual letter to shareholders in February, saying that his management created $50 billion of value for Berkshire. Part of the appeal of being a Berkshire company is that Buffett puts his trust in each subsidiary’s managers – like Nicely – and doesn’t meddle. At the same time, change can be good: Under Geico’s new leader, Bill Roberts, the insurer finally launched a phone app that tracks trips and promotes better driving, akin to the programs that Geico’s rivals have long used to boost profits.

Across Berkshire, there are managers taking it upon themselves to implement positive changes and modernize the company, without threatening the cultural continuity Buffett would like to see. Some executives, including Mary Rhinehart, CEO of Johns Manville – a building-products maker owned by Berkshire – have begun a new tradition of regularly gathering to share strategies, even though Berkshire’s modus operandi has always been for its businesses to operate entirely independent of one another. “We’ve loved being part of Berkshire,” Rhinehart told me at Berkshire’s shareholder meeting in Omaha in May; it’s just that she saw an opportunity to take advantage of the network that the sprawling company has.

That May meeting was a reminder that Berkshire is more than a cash machine that funds Buffett’s high-profile investments or a podium from which to share his views about markets and the economy. Dozens and dozens of individual companies make up Berkshire, each with its own unique brands and challenges. Take Dairy Queen: CEO Troy Bader explained to me how the ice cream chain is studying the rising popularity of dairy alternatives, trying to create “Instagrammable” menu items and looking at delivery for online orders. There’s also the interesting debate taking place around BNSF, Berkshire’s railroad, which has been slow to adopt precision railroading, a strategy that’s helping its competitors become more efficient. The railroad’s net earnings were $1.34 billion, a 2% boost from last year.

In addition to Rhinehart’s and Bader’s businesses, Berkshire’s “manufacturing, service and retail” division comprises aerospace supplier Precision Castparts, chemical producer Lubrizol, McLane wholesale grocery distribution, Benjamin Moore paint, Fruit of the Loom underwear, NetJets private jets, See’s Candies, car dealerships, jewelry and furniture retailers and so on. Together they earned $2.49 billion in the quarter, which was unchanged from 2018.

What drew Buffett to each of these very different businesses was the perceived durability of their brands and market share. How durable are they proving to be? That we don’t quite know because Berkshire doesn’t disclose many details about them in its filings. It’s something I suspect will change once Buffett is no longer in charge. He wrote in this year’s letter that he doesn’t want Berkshire shareholders to “obsess on the details,” as that kind of analysis “can be mind-numbing” given the array of businesses Berkshire owns. But investors demand more transparency from CEOs who don’t have his celebrity and track record. I imagine that over time, folks like Greg Abel – Buffett’s likely successor who functions as chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Energy and also now broadly oversees all non-insurance operations – will conform to more public company traditions, such as hosting earnings calls and providing results on a more granular level.

So often the greatest insight investors get into how Berkshire’s businesses may be doing is by studying the reports of other insurers, railroads and manufacturers. Perhaps that’s another reason so little attention is paid to Berkshire’s own Saturday earnings releases. But even though numerous large companies exist within the company, they are but small next to Buffett.

Slightly more is known about the inner-workings of Berkshire’s various electric utilities and other energy businesses because that division files its own reports and its debt isn’t guaranteed by the parent company.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Tara Lachapelle is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering deals, Berkshire Hathaway Inc., media and telecommunications. She previously wrote an M&A column for Bloomberg News.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.