(Bloomberg Opinion) -- A battle is brewing between Wall Street and stock exchanges. Wall Street says it’s fighting for ordinary investors, but don’t be fooled. Like everything else on Wall Street, this dispute is about the bottom line.

At issue is the cost of market data. Financial firms need price data to trade. They say the exchanges charge too much for that data and that ordinary investors get stuck with the bill. Consequently, they argue, exchanges should give investors a break by lowering fees.

It’s a clever but misguided argument. To see why, a bit of background is needed. Stock exchanges report the trades they execute and their best bid and offer prices to securities information processors, or SIPs, which consolidate the information into a real-time price feed. A group of exchanges and trading firms operates the SIPs, with oversight from the Securities and Exchange Commission, and financial firms pay a subscription fee to obtain access to the feed.

But the exchanges have a trove of other proprietary data that isn’t reported to the SIPs, such as volume and types of orders (market, limit, stop, etc.), and they can deliver it faster than the SIPs. That’s crucial for high-frequency traders and for banks eager to impress well-heeled institutional investors.

The exchanges, of course, are happy to feed Wall Street the data it wants — for a price. Nasdaq Inc. generated $368 million from data products in 2017 — or roughly 15 percent of its revenue — mostly from the sale of proprietary U.S. and foreign market data, according to the company. As long as financial firms continue to profit from the data, the exchanges’ coffers are likely to grow.

Naturally, Wall Street wants to pay the exchanges as little as possible, but that has nothing to do with Main Street. Ordinary investors are migrating to index funds, where the cost can be literally zero. And those who still buy individual stocks can turn to a growing number of online brokers that offer free trading, such as Robinhood and JPMorgan.

For brokers, offering free trades is a no-brainer. The SIP data allow them to execute trades cheaply using the best available prices. In a recent research paper funded in part by Nasdaq, Georgetown University finance professor James Angel estimated that the cost of SIP data for large brokers “is about $0.17 per customer per month, about the same as a sip of Starbucks.” It’s a small price to get investors in the door.

Angel also estimated that the inflation-adjusted cost of at least one SIP feed has fallen 96 percent since 1987. That drop has no doubt contributed to the explosion of low-cost — and now free — trading for ordinary investors, a trend that is likely to continue.

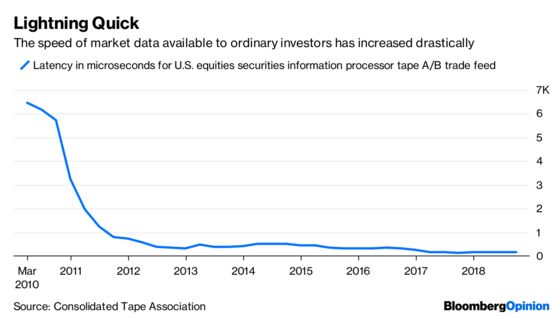

Granted, it’s possible that sophisticated traders are using proprietary data to impose hidden trading costs on ordinary investors. But it’s increasingly unlikely, at least in any meaningful sense, because the speed of SIP data has increased drastically in recent years. On average, it takes the SIPs 17 to 150 microseconds — or millionths of a second — to consolidate and disseminate a trade report, depending on the feed. That delay is down as much as 97 percent since 2010.

Still, none of that seems to soothe concerns that Main Street is paying too much for market data. The SEC recently held a two-day roundtable on the subject, which included a discussion about whether the exchanges’ data products affect “the ability of market participants to obtain the data and access needed to trade effectively in today’s market structure.” Two weeks earlier, the SEC denied the exchanges’ request to raise data fees, saying they hadn’t adequately justified the increases.

In an accompanying statement to the SEC’s decision, Chairman Jay Clayton — my former colleague at Sullivan & Cromwell — rightly points out that markets should serve the interests of ordinary investors. One easy way to do that, Angel says, is to “make clear that brokers can rely on SIP data to execute trades for investors,” which would remove any doubts about the need for more expensive proprietary data.

Ironically, however, this era of free trading ushered in by cheap and widely accessible market data may prove costly for Main Street. I suspect that many investors will use free trading to gamble rather than invest and that some brokers will use it to push predatory products on unsuspecting investors.

Regulators can help. They should promote financial literacy by giving investors the resources they need to be better informed. They should also raise educational and licensing standards for brokers and financial advisers so that ordinary investors have access to the best possible advice.

In the meantime, the battle between Wall Street and stock exchanges is likely to rage on, with no discernible significance to Main Street.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.