Volkswagen Chokes on the Fumes of Past Mistakes

Volkswagen’s engine irregularities were still coming to light as recently as last month, triggering more recalls.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Being in charge of a business during a scandal that misled consumers, spewed pollutants into the atmosphere and helped incinerate billions of your parent company’s capital might get you sacked at many places. At Volkswagen AG, it gets you promoted.

Until his arrest on Monday, Audi chief executive Rupert Stadler had defied any prediction that he might carry the can for the diesel cheating that took place while he was boss. Stadler, who became CEO of the VW unit in 2007, was elevated to a new role overseeing sales across the Volkswagen group as recently as April.

Now he’s in police custody, suspected of trying to influence witnesses. He has previously denied any knowledge of the emissions cheating.

VW appears worryingly unaware of the legal risk that still lingers over “dieselgate” and investors have every right to be unhappy about its handling of the situation. The board couldn’t even agree on a possible caretaker or successor to Stadler on Monday evening. It can ill-afford such indecisiveness, although it did name Bram Schot as an interim replacement on Tuesday. Audi contributes more than one-third of its automotive profit and its cash flows are needed to pay for the scandal. Sorting out its leadership is crucial.

Unlike most senior executives at VW, Stadler is a finance guy, not an engineer. So his insistence that he knew nothing of the engine manipulation was plausible. Still, it’s been hard to see his stewardship as tenable.

Martin Winterkorn, the former CEO of VW, resigned days after the malfeasance came to light, albeit reluctantly. While protesting his own innocence, Winterkorn accepted that someone had to take responsibility. Stadler might have been better advised to have done the same, or the board could have persuaded him.

There has been an ongoing stream of revelations about Audi’s manipulation of diesel emissions. Engine irregularities were still coming to light as recently as last month, triggering yet more recalls.

Audi hasn’t excelled operationally either. There’s a perception that it has slipped behind Mercedes-Benz in technology and design, for example, and the brand’s sales growth slowed last year after a dealer dispute in China. These shortcomings led to a sweeping overhaul of Audi’s management board last year.

Stadler is close to the Porsche and Piech families who control half of Volkswagen’s voting shares, which might help explain their reluctance to let him go. But other investors will still feel a little in the dark. For all VW’s claims about wanting to learn from the scandal and become more transparent, it has been remarkably tight-lipped about who’s to blame.

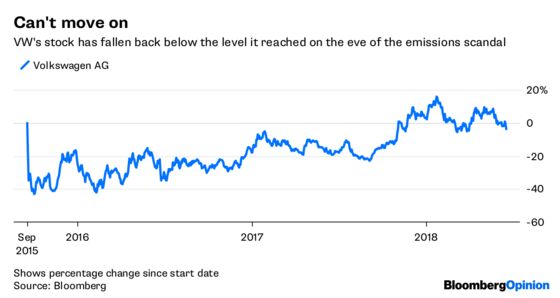

VW suppressed publication of the findings from its own investigation of the cheating, conducted by law firm Jones Day, so outsiders can’t really be sure whom prosecutors will target next. It is unsurprising that its shares are back below where they were before dieselgate. Donald Trump’s attacks on German carmakers aren’t helping, of course. The belief that VW had finally moved on looks sadly premature.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.