Big Tech's European Nemesis Can Take One Last Swipe

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When Margrethe Vestager’s five-year term as European competition commissioner ends in November, the world’s biggest tech companies will breathe a sigh of relief.

The Danish politician has been a thorn in the side of the Silicon Valley giants, imposing back taxes on Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc., and fines on Facebook Inc. and Google parent Alphabet Inc.

“I suspect that, assuming as we all do at the moment that she goes somewhere else at the end of her term, very few people are going to shed a tear about that in Silicon Valley,” said James Aitken, a partner specializing in competition and antitrust law at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP in London.

But the behemoths shouldn’t start breathing easily just yet. As with any politician in the final stretch of their tenure, Vestager will be aiming to secure her legacy as the trailblazing regulator of big tech, so there’s a good chance she’ll initiate new investigations into their activities. Although it’s nigh-on impossible that she would be around to see such inquiries through to their conclusion, by kicking them off, she will still be able to reap some of the plaudits for any success.

Concerns about companies using one part of their business to create an advantage for another is a regular trope of European Union antitrust investigations, according to Nicolas Petit, a law professor at the University of Liege in Belgium. Big Tech looks ripe for coming under this particular microscope.

The examination already started in September for Amazon, and its role as both a retailer and a marketplace for third-party vendors. Vestager is looking to see whether it mines data from the latter to improve its competitive position in the former, such as by working out which new products are most popular, then deciding to offer its own competing versions. Retailer Williams-Sonoma Inc. accused the company of doing just that in a suit filed Dec. 14.

Apple is also an obvious target. Its iPhones and iPads are a walled garden for third-party developers, who must give the company up to 30 percent of any fee customers pay for downloads and other charges via the App Store. Facebook’s practice of using its Onavo app to see which programs are popular among users, then buying those developers up before they become a competitive threat, might also be on her laundry list.

Her run at Google, which has already been pretty fierce – the company now lists "European Commission fines" as a reporting line in its income statement – will continue. The EU is investigating whether its AdSense service stopped websites from displaying advertisements from Google’s competitors, and the results may come before the end of her term.

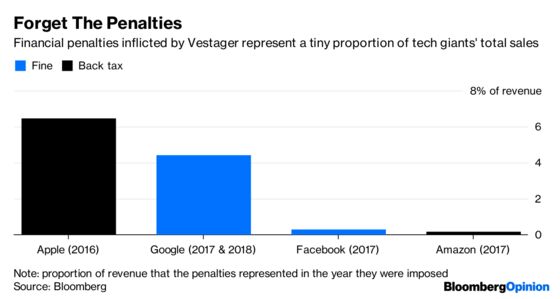

Tech companies’ hundreds of billions of dollars of revenue mean that any penalties will barely register. Of greater concern is whether Vestager shakes the core of their businesses.

It's too early to tell whether Google’s market dominance has been hit by the EU ruling in July barring it from strongarming handset-makers to preinstall its search engine and Chrome browser. However, one lesson from history is worrying. The commission’s 2009 demand that Microsoft Inc. loosen its grip on web browsers and media players played into a directionless period for the company, which it eventually turned around by diversifying into new businesses. But its obligation to offer a number of web browsers on Windows helped encourage the widespread adoption of Chrome, and Google’s growth into a serious rival.

Targeting the Silicon Valley monopolists is healthy at a time when other regulators have been unwilling or unable to do so. However, Vestager’s approach to the telecommunications industry has been excessive, and there’s room for her to encourage a change of direction which her successor can continue to pursue.

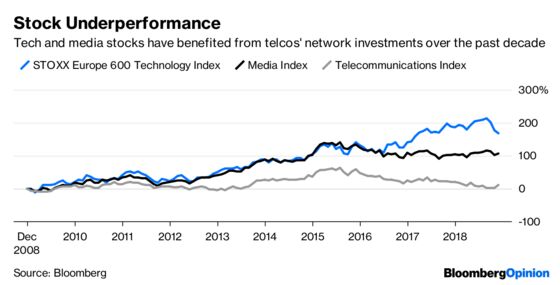

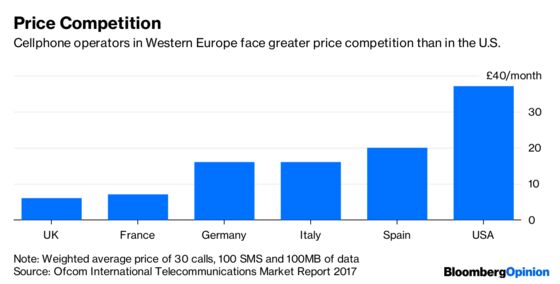

In the 11 years since the iPhone’s introduction heralded the start of the smartphone era, both tech and media stocks have soared. But shares in the telecom companies responsible for building the infrastructure which facilitated that growth have had a more difficult time. Mergers would give them more power over pricing, allowing them to make greater returns on their upfront infrastructure investments. But efforts at deals in the U.K. and Denmark have fallen through after opposition from Vestager, who has prioritized the effect on consumer pricing.

The commission’s responsibility is to customers and consumers. Any operators seeking to consolidate will have to convince it that they wouldn’t otherwise be able to afford to give customers a quality service by making the investments needed to build out 5G networks.

A recent Dutch case suggests the EU is now more open to such arguments. In November Vestager, unusually, cleared the merger of Deutsche Telekom AG’s Dutch operations with those of Tele2 AB with no remedies. The commission pointed out that the firms would only have a combined 30 percent market share, so the deal wouldn’t really change the prices consumers paid or the quality of the service.

This suggests a path for dealmaking Europe. France could do with some consolidation, and its regulator has helpfully said it’s open to a reduction in the number of players from four to three. The European Court of Justice will review the regulator’s block on a merger of CK Hutchison’s Three unit in the U.K. with Telefonica SA’s local division, and the Dutch example would likely serve as a useful precedent for the companies to cite.

And if mergers strengthen the telecoms industry, that could embolden them in negotiations with Silicon Valley giants over purchasing, data sharing and handset subsidies.

Vestager has proven that the competition remit is a great way to build an international profile, making it an attractive role for career politicians on the make. Because her Social Liberal party is no longer in power in Denmark, it seems highly unlikely that she’ll be nominated for another term as commissioner. But she could have a shot at becoming the next president of the European Commission. That means that after November, her position as Silicon Valley’s bugbear might just be getting started.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Alex Webb is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Europe's technology, media and communications industries. He previously covered Apple and other technology companies for Bloomberg News in San Francisco.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.