(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Alan Jope told a podcast in 2016 that he didn’t define himself by his work. Family, football and motorcycling were just as important.

When he takes over as Chief Executive Officer of Unilever on Jan. 1, investors are unlikely to see it that way. They will measure him on his vision for the consumer goods group, and how successfully he implements it.

Jope will succeed Paul Polman, who ran the consumer goods giant for a decade. Although shareholder returns were impressive during his tenure, the Dutch grandee divided investors almost as much as the company’s Marmite brand. His successor has the opportunity to solve what seems to have become an intractable problem: despite its enviable scale and penetration of vibrant emerging markets, Unilever has failed to turbo-charge sales.

To achieve this the new CEO will need as many options as possible, including the ability to execute canny deals. This will require simplifying Unilever’s cumbersome corporate structure.

He hasn’t started well. Just one week after his appointment, he told investors there was “no chance of us backing down” on his predecessor’s goal of lifting the underlying operating margin to 20 percent by 2020, while delivering annual revenue growth of between 3 percent and 5 percent. This is a missed opportunity. Jope could have revised the targets, or at least given himself more time to assess them.

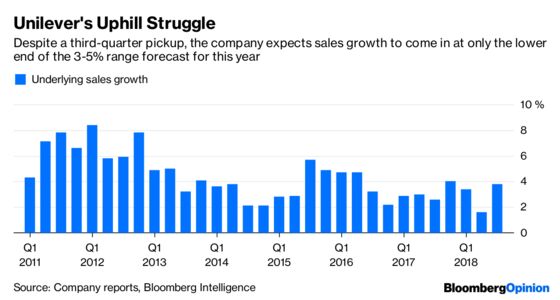

That could prove a costly misjudgment. Unilever has made good progress in lifting the margin. But boosting revenue looks more challenging, and the company looks set to be closer to the bottom end of its forecast range this year. A miss here would be sure to provoke investor ire.

That won’t help him build any bridges with U.K. shareholders. While the stock is not too far from its record high, some of them were angered by the plan to simplify the group’s dual listing into a single company in the Netherlands. They launched an aggressive campaign, and at the eleventh hour, Unilever backed down.

Here Jope has a good chance of success. Not only is he British — it would have been difficult to convince investors to support both a Dutch chairman and CEO after the revolt — his willingness to do punishing burpees on the Spartan UP! motivation podcast shows he’s pretty affable and up for a challenge.

He’ll have to turn on all his Glaswegian charm to get them onside, because he’ll need their support as he decides on Unilever’s broader strategy.

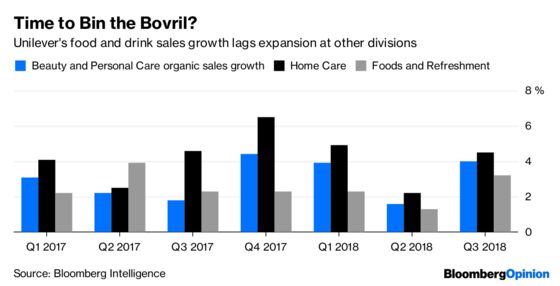

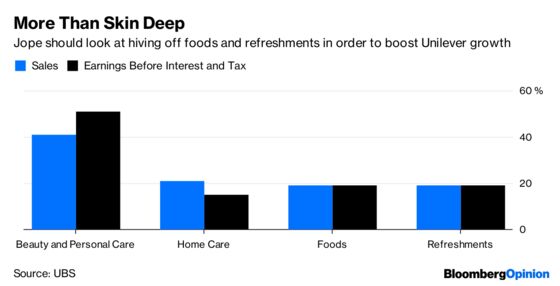

Jope’s background was most recently running the faster growing beauty and personal care division. This is useful, given the need to reorient the group towards businesses most capable of elevating revenue.

The logical way to achieve this is to concentrate on his old stomping grounds, as well as the home arms, and split off food and refreshments. The latter could have an enterprise value of about 55 billion euros ($80 billion), according to analysts at UBS, assuming a 15 percent premium for Unilever’s strong emerging market exposure.

That would also provide firepower for acquisitions, such as Reckitt Benckiser Group Plc’s hygiene and home business, which analysts at Jefferies estimate could be valued at about 20 billion pounds, assuming a 25 percent takeover premium. Another option could be purchasing Colgate-Palmolive Co., which has an enterprise value of about $60 billion.

But a new CEO wants to have as many options as possible. And that’s where the continued existence of both the British and Dutch companies, each with their own class of shares, could be a handicap.

There is nothing to stop Unilever selling off food for cash, as it did with its spreads business. But after that it gets trickier. Having two classes of shares not only makes it more difficult to demerge this division, it also complicates any attempt to use the stock as an acquisition currency for a big U.S. takeover.

So Jope needs to finish what Polman started on both strategy and the structure of the parent company.

When it comes to the latter, there are no easy answers. But to maximize success, Unilever will have to endure the pain either from compensating any U.K. shareholders that would have to give up their holdings, or concocting a hybrid of the Dutch and British entities. Getting to a mix of the two regimes is likely to be a long and arduous task, and still might not deliver an optimal solution.

This is where Jope’s hasty approach to Polman’s targets hits home. Amidst this change, he’ll have little choice but to deliver on them. And he may not have all the time in the world. Though Kraft Heinz looks unlikely to repeat its 2017 approach, given that its own troubles have left its market capitalization at less than half of Unilever’s, a lurch downwards in performance could still attract the interest of an activist investor. After all, not all of them are interested in showy break-ups — Elliott Management Corp. is seeking a better performance at Pernod Ricard SA. Unilever could be vulnerable to just an intervention.

Jope is fond of off-road motorcycling in the likes of Mongolia and Namibia. He will need all of his endurance skills to get to grips with the knotty problems he has inherited.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jennifer Ryan at jryan13@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.