Good Things Come to Those Who Wait for Unicorn IPOs

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The unicorns are coming, and not a minute too soon for many investors.

As Bloomberg News reported recently, a flood of private companies are planning initial public offerings for next year, including behemoths such as Uber, Lyft and Slack Technologies. Airbnb may also add its name to the list.

Investors have been eager to get in, enviously watching humble startups morph into billion-dollar ventures. If only Uber and its cohorts had gone public earlier, investors tell themselves, they, too, could have profited from their rise.

Except it’s an illusion. For every Uber, there are many more startups that investors have never heard about. And even if they had, it would have been nearly impossible to pick the winners in advance, no matter how inevitable their success may seem now. The truth is, startups are doing investors a big favor by putting off IPOs until they’re more grown up.

Investors, who are busy bemoaning the dearth of public companies, are not inclined to hear that. Companies are staying private longer than they used to because, well, they can. Private capital is abundant and allows them to sidestep regulators, Wall Street analysts, short-sellers and Mr. Market’s mood swings. The number of domestic companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges is down to roughly 3,600 at the end of 2017 from more than 7,600 in 1997.

Sure, many of the companies that disappeared from public markets over the last two decades were obscure businesses and penny stocks that investors were unlikely to encounter. But as public companies have vanished, the fame and fortune of private companies has grown, arousing investors’ fear of missing out.

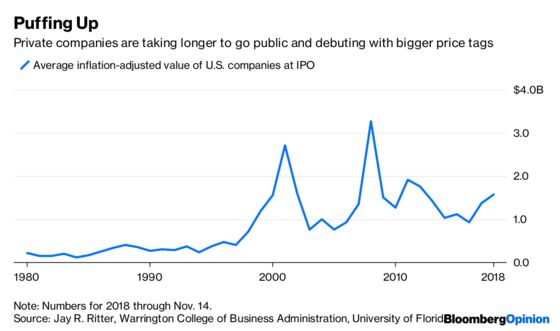

According to data compiled by University of Florida finance professor Jay Ritter, the average inflation-adjusted market value of U.S. companies when they went public was roughly $300 million from 1980 to 1998, the earliest year for which numbers are available. Since 1999, however, that number has ballooned to roughly $1.5 billion. (Those numbers include stocks listed on Nasdaq and NYSE and exclude ADRs, natural resource limited partnerships and trusts, closed-end funds, REITs, SPACs, banks and S&Ls, unit offers and penny stocks.)

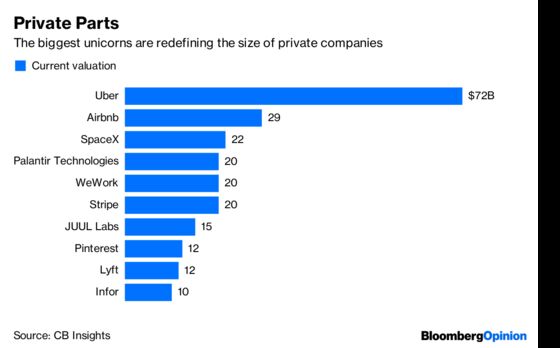

The current stable of unicorns — private companies with a value of $1 billion or more — is much bigger. There are 139 of them in the U.S., according to research firm CB Insights, and their average value is $3.5 billion. The richest among them would already number among the largest stocks by market value if they were publicly traded.

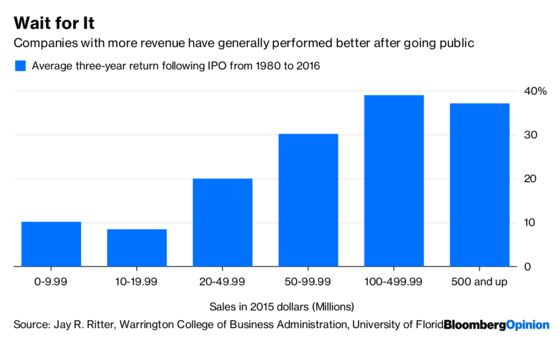

But the fact that companies are taking longer to go public may be a blessing in disguise. Over the last four decades, companies that have gone public with little more than an idea generated a lot of enthusiasm and then faded quickly. Inversely, more established companies received a tepid reception and then thrived.

Consider that from 1980 to 2016, firms with less than $100 million in inflation-adjusted sales posted an average return of 21.9 percent on their first day as public companies, according to Ritter’s data, while companies with $100 million or more in sales notched an average return of just 11.4 percent. Over three years, however, their fortunes flipped. The smaller companies posted an average return of just 11.9 percent, compared with 38.4 percent for the larger ones.

The smallest companies struggled the most. Firms with less than $10 million in sales were up an average of 22.2 percent on their first day. Three years later, their average return was a negative 10.2 percent.

Unless investors have a knack for knowing which startups will succeed, a bet on early-stage companies isn’t likely to be the gold mine they imagine. So the next time they eye that hot new startup still hustling its wares, they should bear in mind that it’s far from a sure thing. To borrow a little from Woody Allen, sometimes to have a little patience is the most brilliant plan.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.