Twitter’s Problem Isn’t the Like Button

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Speculation flew over the past day or so that Twitter was getting rid of its Like button. The social-media company quickly reassured the public that this was just one possible change among many being discussed as part of an internal dialogue about encouraging healthy conversation. But the mere fact that eliminating Like is being considered illustrates the problems with Twitter’s conception of what constructive online discussion means.

The Like button is a much-needed way of delivering positive feedback on a platform that tends to amplify the negative. Likes are a quick, low-effort way of acknowledging a response or signaling approval — the Twitter equivalent of a nod of agreement. In order to see what Twitter is like without Likes, I’ve tried to go two days without Liking any tweets; after about an hour, the inability to give acknowledgment became unbearable and I had to log off. Without Likes, the only ways to indicate that you agree with or appreciate a tweet would be to either respond to it — which is impossible for Twitter users who receive floods of replies — or to retweet it, which is similarly prohibitive because it fills up one’s entire feed and quickly exhausts one’s readers.

And positivity is something Twitter desperately needs. Success on Twitter depends on virality — that is, having lots of people click the Retweet button. Positive tweets often go viral, but negative ones often do as well. When it comes to politics, the latter tend to dominate. A 2013 Pew report found that in the lead-up to the 2012 election, tweets about both Barack Obama and Mitt Romney skewed heavily toward the negative — and that was before the advent of Donald Trump, police-shooting protests and other events that dialed up the rancor in American politics and society. Surveys confirm the generally adversarial, vitriolic character of Twitter discussions.

The platform’s antagonistic slant is clearly demonstrated by the concept of the “ratio.” When a tweet’s ratio of replies to Retweets or Likes is high, Twitter users assume that the tweet was a bad one, thus offering a tempting chance to tell a user that he or she is wrong or stupid. Sadly, this assumption is all too often correct.

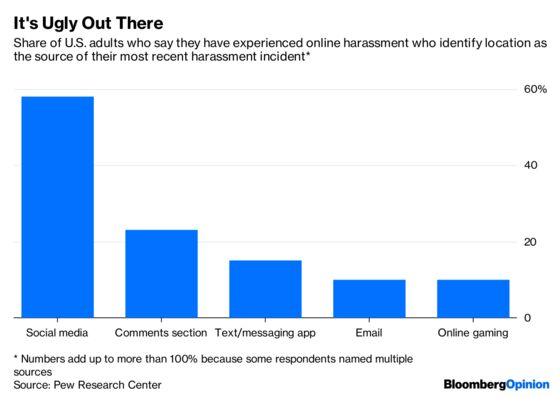

On top of general ambient negativity, Twitter users must deal with frequent harassment. Surveys show that online harassment is pervasive, and that social media is the main vector for those attacks:

For women, Twitter is so toxic that human-rights organization Amnesty International has issued a report about it.

A prime example is the tweets by Cesar Sayoc, the Florida man accused of sending mail bombs to various media companies and public figures who criticized President Donald Trump. Shortly before the wave of mail bombings, Sayoc, tweeting under the alias of Cesar Altieri, sent threatening tweets to Rochelle Ritchie, a former Democratic House of Representatives press secretary:

Twitter staff, when alerted to the abuse, responded that the threats didn’t violate the platform’s rules, and refused to remove the tweets.

The company later apologized for this obvious failure, but it’s not clear that the company learned any real lesson from the incident. From conversations with Twitter employees assigned to stop abuse, it seems to me that their main worry isn’t the negativity or threats on the platform. Instead, what frightens them most is the idea that Twitter might be used to create echo chambers, where like-minded people aren’t exposed to contrary viewpoints.

This focus clearly comes directly from the company’s co-founder and chief executive officer, Jack Dorsey, who recently responded to calls for limiting hate speech on the platform with warnings about the dangers of echo chambers. That suggests that Twitter’s problem of negativity and harassment stem not only from sloppy enforcement or the limitations of the technology, but from a fundamental philosophical difference — much of what many people regard as hate speech, Dorsey and his employees see as valuable disagreement.

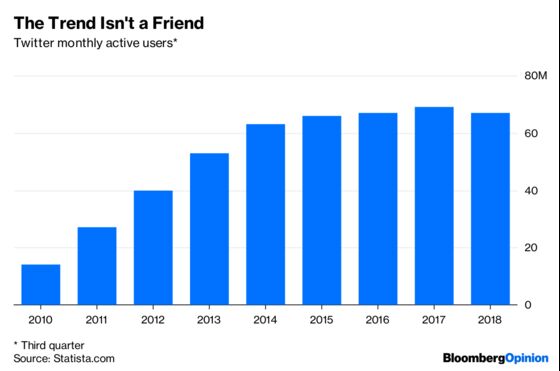

Of course, it’s possible that Twitter’s professed fear of echo chambers is simply an excuse for more bottom-line considerations — Twitter may believe that cracking down on aggression will cause users to abandon its platform. But a look at monthly active user numbers suggest that it’s not doing too well on this front in any case:

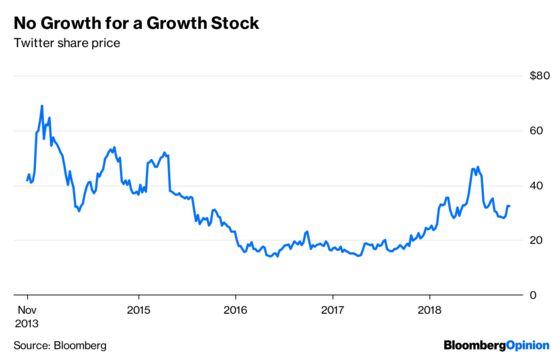

That stagnation appears to have taken its toll on the company’s stock price:

With American user growth nonexistent and the stock price no higher than it was in mid-2015 levels, it’s definitely time for Twitter to rethink its approach to creating public conversations. The notion that harassment and negativity are important for countering echo chambers should be the first to go.

Twitter’s main order of business should be stepped-up enforcement of a ban on harassment — no more letting users like Cesar Sayoc get away with making threats. But there are several other key changes — some of them small, easy steps — that I believe would reduce negativity substantially.

First, tweets from blocked users should no longer appear in the replies to a tweet. This would give users control over the content of the threads their tweets create, much as bloggers have control over the comment sections of their own blogs. It would also greatly reduce the incentive to leave aggressive, hostile replies.

Second, users should be able to lock individual tweets, closing them to replies. This option now is available only for entire accounts. This would prevent angry mobs from piling on.

Third, Twitter should add an option that allows users to view a list of other users who have quote-tweeted them recently. Quote-tweets, in which a user’s tweet is highlighted by a second user, are often used for aggrieved denunciations, and to summon angry mobs. Allowing users to more easily see who is quote-tweeting them would make it easier to block harassers.

If Twitter is serious about making its platform something other than the hate-filled, perpetually angry comment section of the internet, it needs to start taking steps like these. The country’s current mood of rage and intolerance is much more dangerous than any echo chamber. Until it reforms itself, Twitter is making things worse.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.