Trump's Drug-Ad Price Shaming Won't Fix the Problem

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Naming and shaming has become a signature part of President Donald Trump’s drug-pricing efforts. A series of tweets earlier this year managed to push pharmaceutical companies including Pfizer Inc. to temporarily halt price increases.

Sent via Twitter for iPhone.

View original tweet.

The tactic is being taken to a new level with the administration’s plan, officially revealed Monday afternoon by Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar, to force drugmakers to disclose the list price of medicines available under Medicare or Medicaid in their TV ads. The thinking is, if pharmaceutical companies have to reveal what they charge in such a conspicuous way, they may not price medicines so highly to begin with and may be less inclined to increase prices.

For many Americans, the price-shaming plan would be one of the most visible of Trump’s efforts to keep prices down. But it also may be one of its most poorly conceived and least impactful initiatives yet.

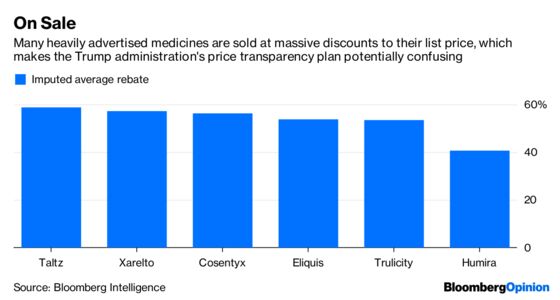

The main issue with the proposed rule is that a drug’s list or sticker price is very far from what many people or their health-care plans actually pay. Almost all drugs, and particularly widely used medicines that warrant big direct-to-consumer ad campaigns, come at a large discount to the price their makers would be forced to disclose in ads.

In fact, the actual cost to patients with health insurance is usually even lower than the discounted price paid by health plans. Patients often only pay a portion of the total price via a co-pay or co-insurance. That can be substantial in some plans — especially for those with high-deductible insurance, a point that Azar emphasized on Monday — but it is often only a fraction of the total price of a drug. Also, drugmakers often offer coupons or other assistance that can defray that out-of-pocket cost.

Most consumers won’t immediately know that the intimidatingly large numbers in an ad aren’t what they would actually have to pay — and it would be rather difficult to explain the arcane details of list prices, discounts, and cost-sharing in a few seconds of voice-over in a TV ad. There’s even a chance that people might be discouraged from attempting to get drugs that benefit them because they incorrectly think they can’t afford them.

This isn’t to say that list prices don’t matter at all or that they shouldn’t come down. At the end of the day, they serve as the extremely high starting point for negotiations. And even after discounts, it can be argued that prices in the U.S. are far too high.

But this isn’t a particularly effective way to deal with that issue. For one, it isn’t clear that this rule will pass First Amendment muster, or that the administration has the authority to require this kind of disclosure. The industry looks set to fight it, and may win.

In the event that the rule actually does take effect, drugmakers are unlikely to lower list prices — a move that comes with serious financial consequences — just to avoid ad awkwardness. The fact that drugs are expensive isn’t news to most Americans. Actually bringing down prices would likely require much more complicated policy interventions, like allowing Medicare to directly negotiate with drugmakers or reforming the patent system.

The sector is also working to get ahead of the rule. The industry lobby group PhRMA announced Monday that it is encouraging its members to direct consumers to information on how much a drug costs in future direct-to-consumer ads. It’s a safe bet that they will be emphasizing that the average cost to patients is usually below the list price.

Transparency is a laudable goal in drug pricing and in health care more broadly, it’s often difficult to tell who is paying how much for what. But instead of helping to resolve confusion for consumers, this rule would likely add to it.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Max Nisen is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering biotech, pharma and health care. He previously wrote about management and corporate strategy for Quartz and Business Insider.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.