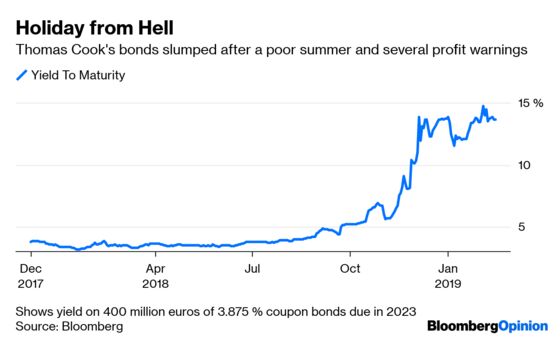

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- In late 2017, Thomas Cook Group Plc refinanced a 400 million euro ($451 million) bond at an attractive rate of just 3.875 per cent, cutting its yearly interest bill by 10 million pounds. The British travel company – whose illustrious history stretches back more than 175 years but which has had an increasingly tough time of it recently – also increased the size of a revolving credit facility to 650 million pounds ($831 million).

In hindsight, its timing was lucky. Summer bookings have been very disappointing subsequently, leading to a series of profit warnings. The bond’s value has slumped by almost one-third, and it yields nearly 14 percent (not a happy sign in credit-land).

The cost of insuring the company’s debt against default has soared and the share price has collapsed, valuing the equity at just 435 million pounds. It was worth five times that in May. Thomas Cook has taken emergency action, including the possibility of selling its airline, but it hasn’t stopped the rot. Some analysts worry that the proceeds of a sale wouldn’t amount to much and that the attempt shows how much the company needs cash to avoid raising more equity. A profit warning from rival Tui AG hasn’t helped sentiment.

In many ways, this is just another story of a bricks and mortar consumer business struggling to adjust to the internet age as customers shun package holidays in favor of direct online bookings. But Thomas Cook’s peculiar accounting merits a closer look too.

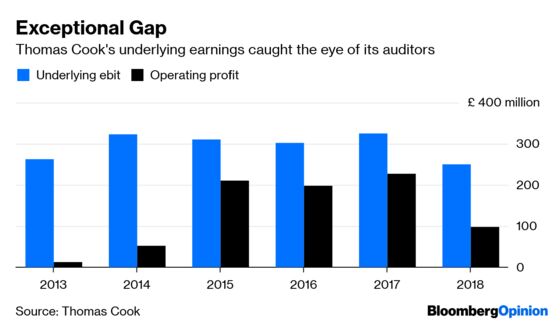

Of particular concern are the flattering profit adjustments made by the company to arrive at what it considers a more relevant “underlying” figure. It’s no surprise that the practice has caught the eye of Thomas Cook’s auditors.

Adding back roughly 150 million pounds of so-called “separately disclosed items,” allowed Thomas Cook to report underlying Ebit of 250 million pounds in the financial year to September. However, reported Ebit – stripping out the impact of those items – was just 97 million pounds, while free cash flow (after investments and interest costs) was a negative 148 million pounds. The cumulative “underlying profit” since 2013 is more than double the reported total, as this chart shows:

Underlying profit features prominently in the company’s annual reports and bond prospectuses. Management bonuses and the company’s banking covenants were also based on these adjusted “pre-exceptional” earnings. These adjustments mostly reflected the large one-off costs needed to transform itself from a high street retailer into a modern digital business and hotel operator.

But it’s not difficult to imagine how this might have encouraged managers to spend too freely, and classify costs as exceptional whenever possible.

In fairness, this isn’t the only company that’s fond of “add-backs” and “exceptionals.” Deciding whether costs are one-offs is inherently subjective, though. Investors and lenders were once pretty tolerant of so-called “alternative performance measures,” but that’s changing as people start to worry about over-leveraged corporate borrowers, as well as greater regulatory scrutiny.

Moody’s, a credit ratings agency, didn’t accept most of Thomas Cook’s adjustments. A “high and growing amount of transformational expenses contrasts sharply with Moody's expectation of their gradual decline,” it warned in December when cutting its junk rating another notch. Analysts and institutional investors have lost patience with the adjustments too.

Thankfully, both Thomas Cook’s auditors, Ernst & Young, and the travel operator’s interim finance director, Sten Daugaard, have demanded a change of course. EY challenged management about certain cost items initially classified as exceptional, and “strongly recommended” that they “strengthen the process over the identification and approval of separately disclosed items,” according to the latest audit report.

The audit specifically draws attention to the link between the underlying earnings and compliance with banking covenants. It’s unusual for auditors to signal their displeasure so clearly – indeed, the profession has been under attack for not being vigilant enough over British corporate failures like Carillion Plc and Patisserie Holdings Plc. But Thomas Cook’s board seems to have taken the hint.

The company reclassified some 14 million pounds of transformation and airline disruption costs as non-exceptional in November, a decision that reduced underlying earnings and helped trigger a profit warning. Management has promised to reduce “separately disclosed items” to less than 100 million pounds in 2019. The annual report notes that in future there will be “an enhanced level of approval prior to recognition of such items.” Thomas Cook’s bonus system will put more emphasis on reported profit and cash generation in future.

“We cannot live off an underlying Ebit,” Daugaard told analysts in November. “We can live off an operating profit or a net income, and therefore… we are going to manage exceptionals in a different way.” His predecessor Bill Scott stepped down that month after less than a year in charge.

The company is fortunate that it doesn’t have to refinance any borrowings until 2022. However, investors might question whether Thomas Cook has made other flattering accounting decisions.

For example, it’s surprising that such a poorly performing company is still showing about 2.6 billion pounds of goodwill (the premium paid for past acquisitions) on its balance sheet. The biggest chunk of that relates to the U.K. tour operator business, which is losing money. The balance sheet value assumes that the British unit’s “underlying Ebit” will increase 28 percent annually for the next four years. That seems mightily optimistic given the uncertainty of Brexit and fierce competition in the travel industry.

Needless to say, a writedown would look very bad. Thomas Cook’s bondholders are already jumpy and the group has just 290 million pounds of net assets. “I’m waiting on an impairment of goodwill,” says Berenberg analyst Stuart Gordon. “The consumer environment is against them turning round the U.K. business in a hurry.”

All this leaves Thomas Cook in a bind. Classifying more costs as regular, rather than exceptional, is the prudent approach. But it might make it harder to comply with banking covenants and protect its balance sheet. The lesson here is that directors and lenders should have been less tolerant of big earnings adjustments in the first place. Unlike cash, adjusted profits won’t help you pay down debt or your bills.

Net debt swelled to 1.6 billion pounds at the end of December a sum which exceeds the 1.4 billion pounds of borrowings and finance leases.

There was an additional 26 million pounds of separately disclosed finance items.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.