The Fed’s Risky Plan to Boost Unemployment

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The U.S. Federal Reserve appears to be planning a risky endeavor: Sometime in the first half of the next decade, it intends to slow the economy enough to increase unemployment by about 1.4 million people — all in the name of reducing inflation by around a tenth of one percent.

I can’t help but wonder whether the costs will outweigh the benefits.

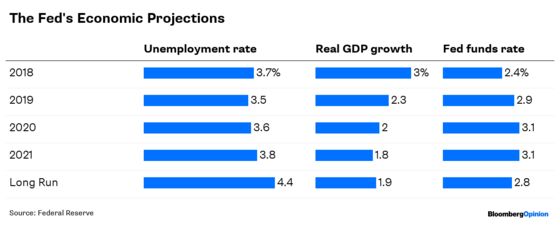

Earlier today, the policy-making Federal Open Market Committee released its latest projections for variables such as unemployment and gross domestic product. These are particularly interesting because they assume appropriate monetary policy: They show not just where Fed officials think the economy will go, but where they intend to take it.

What, then, is the Fed planning? Let’s consider unemployment. The projections show that officials expect the unemployment rate to fall to 3.5 percent in 2019, from the current 3.7 percent — already the lowest in almost five decades. After that, they expect the rate to rise back to 4.4 percent — which, given a labor force of 160 million, would add up to about 1.4 million extra unemployed people.

To achieve such an increase in unemployment, the Fed will have to hit the brakes hard enough to bring economic growth below its long-run normal pace, which officials currently estimate at 1.9 percent a year. Yet the central bank isn’t saying exactly when that will happen. Its forecasts for the next two years are at or above 1.9 percent, with a slight slowing in 2021. All we know is that most of the adjustment will have to come sometime after 2021.

It’s hard to know exactly how much the Fed will need to slow the economy to increase the unemployment rate by almost one percentage point. A rough guess is that it would have to shave about 2 percent off cumulative growth in real GDP. So if the Fed wanted to accomplish the unemployment increase in one year, it would have to shrink the economy by 0.1 percent in that year. If it wanted to take four years, it should hold annual growth to 1.4 percent. All this assumes that the economy returns to normal growth after the target is hit.

Keep in mind that there’s no recessionary shock — such as a financial crisis or trade war — causing the increase in unemployment. To slow growth, the Fed is planning to raise its interest-rate target above its long-run level of around 2.8 percent. We can actually see this happening in the Fed’s rate forecasts for the next three years. But shaving two full percentage points off cumulative growth will almost certainly require the Fed to hold rates above normal for much longer, and possibly by a lot.

This seems like a perilous plan. After all, it might not be easy to increase unemployment to 4.4 percent without overshooting to 5 percent or even 7 percent. So why would the Fed take such a risk? Because it wants to hit its 2-percent target for inflation. Its economic models suggest that, if the unemployment rate stays at 3.5 percent, inflation will remain above 2 percent for years to come. Specifically, the models predict that inflation would be around 2.1 percent to 2.2 percent.

In other words, the Fed is planning to eliminate over a million jobs — and put millions more at risk — in order to avoid a tiny deviation from its inflation target. I’ll leave it for readers to judge whether this is a desirable gamble.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Whitehouse at mwhitehouse1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Narayana Kocherlakota is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He is a professor of economics at the University of Rochester and was president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis from 2009 to 2015.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.