Surging Bond Yields Are the Stock Market’s Next Problem

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- First it was China Evergrande Group’s debt crisis, then it was the Federal Reserve’s policy meeting, while in Washington there’s been the continuing kabuki theater around raising the U.S. debt ceiling. Now there’s another pressing item on the list for the stock market to potentially worry about: U.S. Treasury yields.

After initially falling after Wednesday’s Fed decision, yields on benchmark 10- and 30-year Treasuries surged more than 10 basis points on Thursday. The yield on five-year notes, which is especially sensitive to the projected path of central bank policy, nearly reached a 2021 high. It all comes amid a backdrop of more aggressive central bank forecasts and actions: Not only did the Fed indicate it’s on track to announce a tapering of its bond purchases in November, but the Bank of England raised the prospect of increasing its short-term rate before the end of the year and Norway delivered the first post-crisis rate hike among economies with the world’s most-traded currencies.

Bloomberg’s rates/FX strategist Alyce Andres likened the move in Treasuries to a “delayed taper tantrum.” To some investors, though, these moves by central banks are good news. “It’s because the economy is doing so well. That’s not necessarily bad for stocks,” Chris Gaffney, president of world markets at TIAA Bank, told Bloomberg News. Indeed, the S&P 500 Index rallied 1.3% on Thursday, even as Treasury yields climbed. It has been a fool’s errand to bet against the staying power of U.S. equities during the past 18 months.

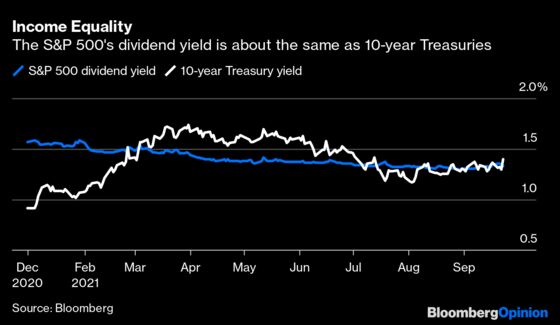

That doesn’t mean the relentless rally in U.S. shares hasn’t had its share of hiccups. In fact, some of the most recent pullbacks coincided directly with the 10-year Treasury yield widening its advantage over the S&P 500’s dividend yield. As it stands now, the two are about as intertwined as they’ve been over the past decade.

On Thursday, the 10-year Treasury yield reached 1.41%, the highest in more than two months and right at its 100-day moving average. That compared with the 1.33% dividend yield on the S&P 500. The gap was about that wide on Sept. 7, which began a period in which the index slid in nine of 11 sessions. A similar thing happened in mid-July: An increase in the 10-year yield put it almost 9 basis points above the S&P 500’s dividend yield, which in turn sparked an almost 3% decline in the equity benchmark in less than a week.

I last wrote about this simple relative-value comparison in February, just as longer-term Treasury yields began roaring higher. While the sharp move didn’t derail the broader market, elevated rates and general economic optimism were enough to topple trendy investments such as Cathie Wood’s flagship ARK Innovation exchange-traded fund, which is still down more than 20% from its highs. The general principle is that Treasuries are used to calculate the present value of future cash flows; when yields are low, investors are willing to pay up for earnings that may not materialize for years.

Obviously, the companies in the S&P 500 and other large indexes have more stable business models and reliable cash flows than many of the high-flying growth stocks that Wood favors. And the so-called “Fed model,” which compares the earnings yield to 10-year Treasuries, still points to an advantage for stocks. Still, big and small firms alike have benefitted from record-low borrowing costs and insatiable demand for corporate debt from yield-seeking investors. And U.S. share prices in general have constantly found a bid because of the view that “there is no alternative,” or TINA.

A sub-2% yield on the long bond and a 1.4% rate on 10-year Treasuries is still nothing to write home about, of course, and neither could be considered a true “alternative.” Until there’s evidence to the contrary, it’s simply too painful for investors to bet against stocks “only going up.”

But if central banks follow through on dialing back accommodation in the face of roaring markets and wealth accumulation — U.S. household net worth rose $5.8 trillion in the second quarter to a record $141.7 trillion — that’s one major pillar of support removed from the stock market. It’s only made worse if bond traders take Fed Chair Jerome Powell and his peers at their word and push long-term yields higher.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Brian Chappatta is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering debt markets. He previously covered bonds for Bloomberg News. He is also a CFA charterholder.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.