Smart Money Doesn’t Think Investors Are Safe Yet

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&w=200)

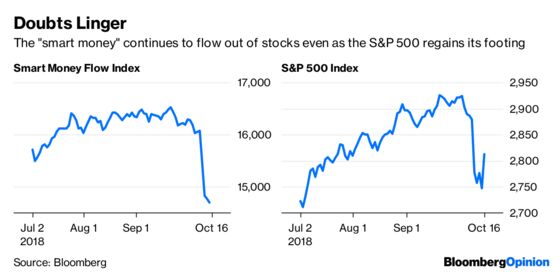

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Back to normal. That’s what it must seem like after the S&P 500 Index surged 2.15 percent Tuesday in its biggest gain since March. The benchmark is now up 2.99 percent since closing on Thursday at its lowest in more than 14 weeks following a gut-wrenching two-day sell-off in which the S&P 500 plunged 5.28 percent. There’s just one problem: the so-called smart money isn’t ready to declare the all-clear signal.

That can be seen in the Smart Money Flow Index, which measures action in the narrower Dow Jones Industrial Average during the first half-hour of trading and the last hour. The thinking is that the first 30 minutes represent emotional buying, driven by greed and fear of the crowd based on good and bad news as well as a lot of buying on market orders and short covering. The “smart money,” though, waits until the end of trading to place big bets when there is less “noise.” That index on Monday dropped to its lowest since March 2009, implying little faith in the prospect for stocks. That’s an issue for the bulls and those who contend strong corporate earnings will help the market regain its footing. And while the economy and corporate profits are good right now, there are plenty of warning signs. For example, as a seller of factory-floor and construction site basics ranging from nuts and bolts to welding equipment, Fastenal Co. should be booming. And yet its shares tumbled more than 7 percent on Wednesday after warning that new U.S. tariffs on China-sourced goods are “directly impacting" its customers. And on Tuesday, another distributor of factory-floor basics, W.W. Grainger Inc., tumbled the most in 19 years after posting profit margins that fell below expectations.

As Bloomberg Opinion’s Brooke Sutherland notes, “concerns are rising that we are nearing a peak for industrial earnings as the trade war accelerates an increase in costs and a forced recalibration of supply chains threatens demand dynamics.” That dovetails with the results of Bank of America Merrill Lynch’s latest monthly survey of 231 fund managers with $646 billion under management. The survey, released Tuesday, revealed that a record 85 percent of fund managers say the global economy is in late cycle, 11 percentage points ahead of the prior high recorded in December 2007. Also, 38 percent expect growth to decelerate over the next 12 months, the most pessimistic outlook since November 2008.

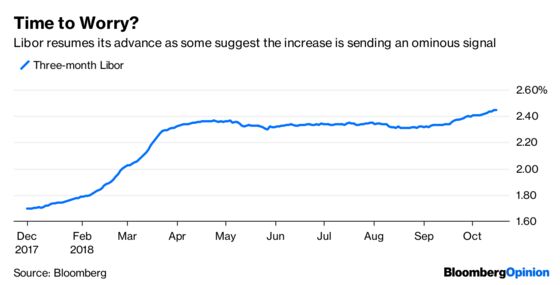

LIBOR IS SAYING SOMETHING

While we’re on the subject of down arrows, some market participants are starting to watch the London Interbank Offered Rate for dollars with a bit of worry. After doing a whole lot of nothing since March, three-month Libor has started to move higher and nobody is quite sure why. Perhaps it’s a reflection of the hawkish rhetoric lately from Federal Reserve officials, who have made clear that almost nothing is standing in the way of further interest-rate increases. But that’s been the Fed’s message all year. A more ominous interpretation is that Libor’s advance over the past month or so reflects a looming liquidity crisis as a slowing economy sparks a massive demand for dollars, especially from heavily indebted emerging-market borrowers. To be sure, demand for dollars tends to rise toward the end of the year, but the latest moves seem to go beyond that. As BNY Mellon senior currency strategist Neil Mellor points out, higher rates in the U.S. are pressuring those nations with big dollar-denominated debts. Citing Bank for International Settlements data, Mellor wrote in a research report Tuesday that dollar-based credit to nonbank borrowers outside the U.S. rose to $11.5 trillion at the end of March, an increase of 7 percent from a year earlier. One-third of that was to a borrower in an emerging market. “Even if the Fed were only able to implement a portion of its plans for tightening over the next 18 months, pressure on funding is only going to grow with negative repercussions for the credit structure across the emerging markets,” Mellor wrote.

WHAT IF CHINA IS A MANIPULATOR?

And if the smart money and Libor aren’t enough to raise blood pressures, remember that there’s a chance that any day now the U.S. might label China a currency manipulator. Although the designation wouldn’t trigger any sanctions or other U.S. penalties, it would most likely escalate the already high trade tensions among the world’s two-largest economies, potentially upsetting markets and paving the way for other actions down the road. “Slapping a ‘manipulator’ label on China would further sour the relationship without advancing any economic purpose,” Bloomberg Economics chief Asia economist Chang Shu wrote in a research note. “In practical terms, it would add another dimension to an already-challenging process of restarting stalled trade talks.” Perhaps more important, it might finally push China’s yuan beyond the psychologically important 7 per dollar level, which may cause international investors to pull their money out of China for fear of further weakening in the yuan. The consensus is that there would be a ripple effect on the global economy, weighing on financial markets. Chinese authorities may not view 7 per dollar as any “psychological threshold to defend,” Liu Li-Gang, the chief China economist at Citigroup Inc., wrote in a note. Robin Brooks, the chief economist at the Institute of International Finance, isn’t as concerned. In a Twitter posting, he wrote that the market’s fixation on the 7 per dollar level runs counter to China’s foreign-exchange policy since 2015, which has tried to get markets accustomed to yuan volatility to reduce the potential for capital flight when the currency drops. We may soon find out if those efforts worked.

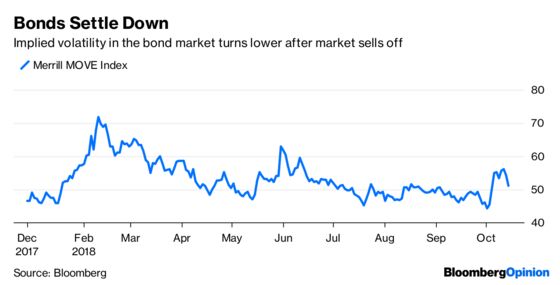

AT LEAST THE BOND MARKET IS CALMER

That’s not to say there aren’t some reasons to be positive. Perhaps the biggest is that the bond market has calmed way down. The sell-off in U.S. Treasuries that pushed yields on benchmark 10-year notes from about 2.81 percent in late August to as high as 3.26 percent on Oct. 9 caused a lot of anxiety and forced equity investors to reprice stock valuations. But since then, yields have eased back to 3.16 percent and trading patterns in the bond market suggest traders are in no rush to retest those highs in yields anytime soon. That can be seen in the Merrill Lynch MOVE Index, which tracks expected volatility in the $15.3 trillion market for Treasuries. The index surged from 44.3 on Oct. 1 to 56.1 on Oct. 11, before dropping back to 51.2 as of Monday. The important thing to know about those numbers is that the latest reading is back below the average for the year of 53. This can be interpreted as traders seeing little chance of a disorderly bear market in bonds that upends the global financial system. It’s also hard to have a prolonged downturn in the bond market without signs that inflation is accelerating, and right now there are none. The Fed’s preferred measure of inflation has dropped, with the three-month annualized rate for the core personal consumption expenditure index, which excludes food and energy, falling from a recent peak of 2.2 percent to 1.8 percent in August. As a result, breakeven rates on five-year Treasuries — a measure of what traders expect the rate of inflation to be over the life of the securities — stands at 2 percent, down from this year’s high of 2.17 percent in May.

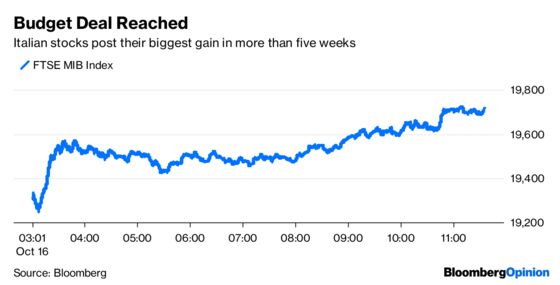

ITALY IS A SOURCE OF OPTIMISM. REALLY.

It was just last week that Italy’s stock and bond markets took a pounding as it appeared the country was headed toward a fiscal crisis with the government unable to agree on a budget. But on Tuesday, Italy’s fractured coalition government managed to cobble together a last-minute accord that starts delivering on costly election promises but risks a confrontation with Brussels over European Union fiscal rules, according to Bloomberg News’s Gregory Viscusi and Lorenzo Totaro. The plan calls for a budget deficit of 2.4 percent of gross domestic product next year, which the government thinks will help accelerate economic growth to a 1.5 percent annual rate from 1.2 percent this year. But the European Commission wants Italy to stick to its pledge to cut debt, which the plan doesn’t exactly do. At more than 130 percent of gross domestic product, the debt load is the largest in Europe in absolute terms and second only to Greece’s as a percentage of the economy. Nevertheless, markets rewarded Italy’s government for coming up with something. “This coalition is showing a greater ability to work together and to move policy forward than anticipated,” Antoine Bouvet, an interest rates strategist at Mizuho International Plc., told Bloomberg News. “But that is not necessarily good news” for Italian bonds “in the longer run,” he added. Yields on Italian two-year bonds tumbled 16 basis points to 1.30 percent. The FTSE MIB Index of equities jumped 2.23 percent, compared with a 1.58 percent increase in the STOXX Europe 600 Index.

TEA LEAVES

More than a few market participants have at least partly blamed last week’s turbulence in equities on President Donald Trump’s criticisms of the Fed. It doesn’t do a whole lot for investor confidence when the so-called most powerful man in the world lashes out at the most powerful financial institution in the world. Trump hasn’t said anything publicly this week about the Fed, but that could change Wednesday, when the central bank releases the minutes from the Sept. 25-26 Federal Open Market Committee meeting where policy makers raised interest rates for the third time this year. At the meeting, the broad majority of policy makers signaled a preference for an additional rate increase in December. According to Bloomberg Economics, the minutes should be closely parsed “for sources of vulnerability regarding policy makers’ collective conviction — the extent of inflation weakness or tightening of financial conditions — that could lead them to consider either a near-term pause or a slow trajectory of hikes next year.”

DON’T MISS

Bond Market’s Rout Makes Forecasting Fun Again: Brian Chappatta

What We’ve Learned From Italy's New Budget: Ferdinando Giugliano

Grainger’s Whiff Intensifies Earnings Jitters: Brooke Sutherland

Shrinking Hasn’t Stopped Japan From Growing: Daniel Moss

Matt Levine’s Money Stuff: Carl Icahn Wants to Fight Dell Again

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.