Russian-Saudi Oil Cooperation Won’t Last

They say they will cut production. But it’s in the interests of both big oil producers to pump as much as they can.

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- There’s a nasty undercurrent to the surprisingly strong Saudi-Russian oil alliance behind the upcoming oil production cuts (or, rather, the latest coordinated verbal intervention to drive up the price of oil). Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman may high-five Russian President Vladimir Putin in public, but he makes no secret of his expectation that Russia will disappear from the oil market in less than 20 years.

That the cooperation is openly tactical rather than strategic is important for the oil market’s future. Eventually, perhaps soon, the two big exporters may not be interested in production-cutting deals as they square off for important markets and seek to keep the U.S. out of them.

In a Bloomberg interview in October, MbS, as the prince is commonly known, explained his long-term vision for the oil market: Even if the demand for oil starts declining after 2030, “countries will continue every day to disappear as countries producing oil. Nineteen years from today, Russia will have declined heavily if not disappeared with [its] 10 million barrels [a day],” he said. “So comparing the rise of the demand for oil and the disappearing supplier, Saudi Arabia needs to supply more in the future,” MbS said.

He didn’t elaborate, but the prediction likely is based on the sizes of leading producers’ oil reserves.

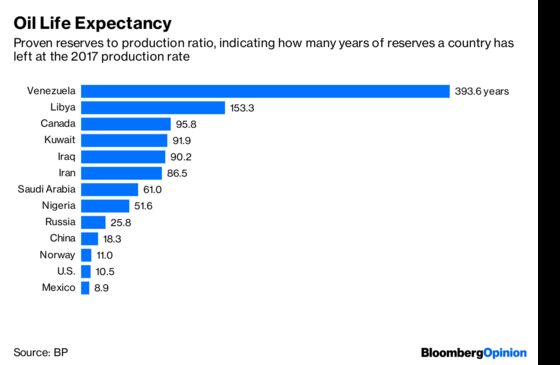

Making predictions about how much oil a country has left is a complicated business. Based on the 2018 BP Statistical Review of World Energy, which uses data from official and some third-party sources, Russia’s proven oil reserves will be exhausted in about 26 years at the 2017 production rate, while Saudi Arabia has some 61 years of pumping left.

Proven reserves, however, aren’t the best measure to use. They only reflect how much oil a country can expect to extract with reasonable certainty under current economic and operating conditions. But new discoveries happen all the time, extraction technology improves, market prices fluctuate. Besides, official numbers can be overoptimistic.

It’s often worth going into iffier territory. Rystad Energy, the energy research company headquartered in Norway, does that with four different estimates of reserves and resources for each country, including, at the outer limit of probability, undiscovered fields. Using Rystad estimates of “proved plus probable oil reserves plus mean contingent recoverable oil resources in yet undecided projects/discoveries, including noncommercial volumes” – two levels of uncertainty up from proven reserves – provides only a slightly different picture for Russia and Saudi Arabia, giving them 28 and 56 years of oil production at the 2017 level, respectively.

Based on existing data from various sources, MbS has reason to believe that before the electrification of cars and other oil replacement technology slashes the global demand, some big current producers will be gone. Mexico is one, China could be another (in the Bloomberg interview, MbS predicted China would sharply cut its own production five years from now – likely an overoptimistic estimate, but based on BP numbers, it’s got only 18 years left). And Russia will likely be gone from the market before Saudi Arabia is.

That’s not necessarily much of an advantage. Keeping a lot of oil in the ground for the almost inevitable low demand era isn’t the best strategy for Saudi Arabia. Cutting production only makes sense as long as it causes big increases in the price – but even that may not be important soon; the Kingdom’s breakeven price needed to balance the budget is $74.4 a barrel this year, down from $105.7 in 2014, and, according to some predictions, it may go down to $55 by 2021.

Russia, given its lower reserves, should be more amenable to production cuts that drive up the price – but only tactically. Its long-term strategy is to use its ideological flexibility and military strength to get its hands on the oil resources of Venezuela and Libya, where Russian state companies can count on concessions by backing the leaders most hungry for foreign support, and to cut Russia’s own dependence on oil exports. The country balances its budget at $50 per barrel this year and hopes to keep bringing that down.

In addition to all this, neither Saudi Arabia nor Russia is interested in cutting production so that the U.S. keeps increasing its own and becomes a competitor in global markets. Rystad data suggest the U.S. can keep pumping at current rates longer than Russia; there's no reason to help U.S. shale players increase production any further by driving up the price. As it is, Russia and Saudi Arabia compete in major markets, such as China’s, and Russian officials would like to expand the contest to other parts of Asia. The possibility of U.S. exports into the same markets is unappealing.

In other words, high-fives and dictatorial solidarity aside, neither Russia nor Saudi Arabia desires long-term cooperation on production cuts. In the coming years, both will want to pump as much oil as they can. That may be why big output cuts aren’t on the agenda even now: A total of 1 million barrels a day from the Organization of Petroleum-Exporting Countries plus Russia, which was being discussed at the OPEC meeting in Vienna, would hardly be earth-shaking.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Therese Raphael at traphael4@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering European politics and business. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.