(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Australia’s investigation into misconduct within its financial-services sector is moving toward the last act. Just don’t expect to see the bad guys get punished.

The Royal Commission, which published its interim report Friday, has heard a litany of bad practices the country’s banks, insurers, financial advisers and others have committed, from charging dead people fees to duping the corporate regulator.

The question is what to do about it.

The main themes Commissioner Kenneth Hayne struck are very much in line with what we’ve been arguing in recent months: The problem lies in the structure of the financial system and weak enforcement of misconduct.

So more laws won’t necessarily improve the situation. Hayne wrote:

I begin from the premise that no new layer of law or regulation should be added unless there is clearly identified advantage to be gained by doing that. And I begin from the further premise that very simple ideas must inform the conduct of financial services entities.

That’s a wise approach. One telling conclusion from the report is that financial-system complexity generally works for incumbents and against consumers and regulators. Empowering watchdogs and breaking up the structures with the most egregious benefit to the major players will have a bigger impact than another set of rules that will be gamed as soon as they’re passed.

At the same time, it’s a conclusion that depends upon continued and bipartisan political attention. Even in the heat of the current Royal Commission proceedings, that can’t be counted on: Prime Minister Scott Morrison, in his previous role as treasurer, cut funding for the country’s main corporate regulator to its lowest level in real terms since 2006 in his May budget. Whether a Royal Commission should even have been called was a bitterly fought partisan issue for more than a year before the inquiry was finally announced last November.

Another aspect of Hayne’s preliminary findings is the importance of structural issues. Banks can get caught up in wrongdoing when employees are paid to hit sales targets shared by their managers, which ultimately comes back to senior executives trying to fulfill a fiduciary duty to shareholders. Equally troublesome activity tends to creep in whenever third-party brokers are hustling to funnel business to major players in return for sales commissions.

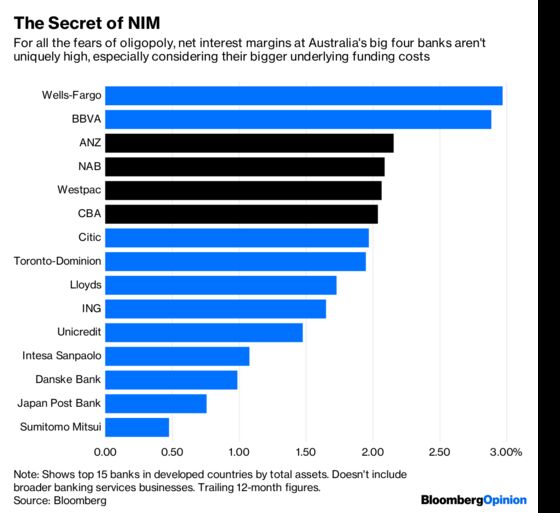

That helps explain how Australia’s banks manage to be oligopolistic and competitive at the same time. Net interest margins are actually reasonably tight in global terms, especially when compared with the benchmark rates that underpin their funding costs. But the secret of the big four’s success isn’t so much the margin they claim on existing business, but their remarkable ability to take the lion’s share of new business despite the availability of cheaper options, thanks to their stranglehold on distribution.

Again, though, it's hard to be confident that any reform will stick. The best way to stamp out a “sales culture,” while ensuring companies work for the benefit of shareholders, is ultimately the draconian one adopted in Europe and North America: Impose devastating, profit-killing fines on bad practices so that senior managers police conduct for their own good. Though the penalties available to the Australian Securities and Investments Commission have been beefed up, the cuts to its budget don’t suggest that’s the way things are headed.

Likewise, the conflicts of interest between brokers and lenders have grown organically, rather than through policies invented by the banks all at once. Without continued attention, it’s hard to believe that future developments in the market won’t be accompanied by similar problems.

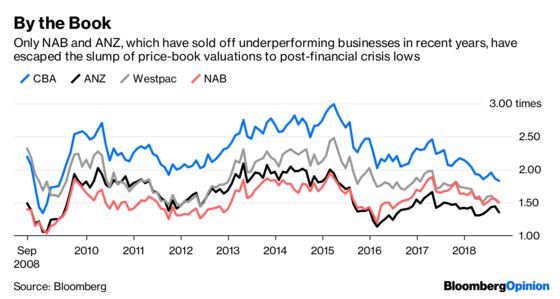

Right now, thanks to the Royal Commission and an 11-month slump in home prices, bank valuations are at crisis levels. The price-book ratio of Commonwealth Bank of Australia, the country’s largest lender, is currently at 1.82, its lowest since May 2009. The figure at second-ranked Westpac Banking Corp. is lower than during the 2008 financial crisis.

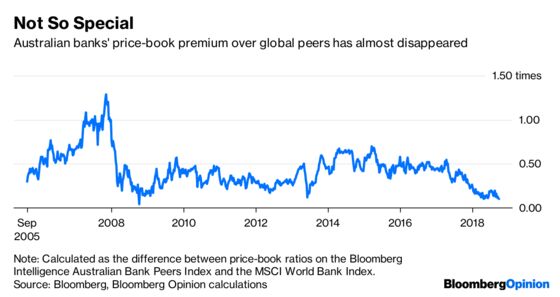

Compared to peers overseas, the picture is even more striking.

Over the 13 years for which there’s comparable data, the price-book premium for Bloomberg Intelligence’s index of Australia’s larger banks over the MSCI World Bank Indexhas averaged a hefty 0.43. It’s now down at just 0.1, a depth tapped only in the teeth of the financial crisis in October 2008 and June 2013, when the end of Australia’s mining boom, a slumping currency and the taper tantrum saw funding costs rise alongside a slowing economy.

That seems overdone, as indicated by the financials sub-index of the S&P/ASX 200, which rallied as much as 2.1 percent after the report was released and is headed for its biggest one-day jump in three months.

Only long-term regulation and enforcement fearsome enough to threaten profitability as a whole can shift that balance in favor of customers, and that doesn’t look all that much more likely after Friday’s report. The cynic right now would see current valuation weakness as an opportunity to go long Australian banks – and short their customers.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rachel Rosenthal at rrosenthal21@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.