(Bloomberg Opinion) --

The Federal Reserve has spoken, again. So I will write about the Fed, again. After three days of intensive parsing of every word, every space, and every space between every line of two speeches by the central bank’s chairman and vice chairman, and the minutes of the latest Federal Open Markets Committee meeting, everyone agrees that the Fed is a little less aggressive in its outlook for monetary policy. As a result, investors are adjusting their expectations for how high the target federal funds rate gets and when it gets there. But it seems clear that we should regard the latest rhetoric as just that: an adjustment and not a significant change.

The FOMC minutes released Thursday didn’t prompt any great rethink of Wednesday’s rally, which was driven by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell’s description of the current federal funds rate as being “just below” a range of estimates of what is deemed neutral (neither restraining nor stimulating growth). Critically, this was different from a Q&A session on Oct. 3, when he said the rate was “a long way” from neutral. The benchmark 10-year Treasury note’s yield has now come to rest almost exactly where it opened on the morning of Powell’s “long way” comment.

However, a big chunk of this is due to a decline in inflation expectations, which may have been driven by falling oil prices. If we look at 10-year real yields, which is what holders get after accounting for inflation, we get a slightly different picture. In the following chart, the white line represents the “long way” comment and the red line marks this week’s “just below” speech:

The real yield burst through the 1 percent barrier on the day of the “long way” comment, and it remains just above that level even after the “just below” speech. The upward trend in real yields remains intact even though the 10-year yield has dropped to just above 3 percent. My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Daniel Moss suggests that the “long way” comment was a “rookie error” of a kind that former Fed Chairman Ben S. Bernanke made on several occasions in his first few months in office, while Bloomberg Opinion’s Brian Chappatta suggests that 3 percent yields are a “magic number” and will trade in a narrow range for a few weeks. In the interests of ensuring that Bloomberg furnishes you with the widest possible range of opinion, I would like to suggest that the market is still underestimating the Fed’s willingness to raise rates, or underestimating the U.S. economy’s likely strength, or both.

The critical point in the minutes from the Nov. 8 FOMC meeting, which you can read here, is that policy makers expected to continue hiking rates gradually. This is the key passage, in which members judged that “the economy had been evolving about as they had anticipated at the previous meeting”:

Financial conditions, although somewhat tighter than at the time of the September FOMC meeting, had stayed accommodative overall, while the effects of expansionary fiscal policies enacted over the past year were expected to continue through the medium term. Consequently, members continued to expect that further gradual increases in the target range for the federal funds rate would be consistent with sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective over the medium term. Members continued to judge that the risks to the economic outlook were roughly balanced.

This is not hugely hawkish, but it means that we should expect more than just one additional rate increase barring some absolute shocker in the monthly jobs report next week. With the labor market as strong as it is, that should continue to be the default expectation. As for December, the federal funds rate will rise and then:

Consistent with their judgment that a gradual approach to policy normalization remained appropriate, almost all participants expressed the view that another increase in the target range for the federal funds rate was likely to be warranted fairly soon if incoming information on the labor market and inflation was in line with or stronger than their current expectations.

The Fed has been admirably fair and clear about the need for more rate increases. It was a little silly to suggest that Powell’s language adjustment Wednesday had really changed that, but it’s worth making the point because the market still seems to be underpricing the chance of even a December rate hike. According to Bloomberg’s World Interest Rate Probabilities function, there’s a 21.3 percent chance that the Fed will leave rates unchanged. I would say that that’s at least double the correct probability.

Meanwhile, I continue to think that the crucial variable, and the next fault line between the Fed and the markets, will be over the reduction of its balance sheet assets. There was a discussion of this in the minutes, which ended with no hint that the end is in sight. The strategists at Societe Generale SA published a note highlighting this passage:

“Participants noted that the level of reserve balances required to remain in a regime where rate control does not entail active management of the supply of reserves was quite uncertain, but they thought that reserve supply could be reduced substantially below its current level while remaining in such a regime.”

In another place, we learned that policy makers believe that reserves can be “reduced substantially” without jeopardizing their operating framework. Plenty of people out there in marketland think the Fed is wrong about this, and that a shortage of dollars will soon become a major issue. Meanwhile, the muted Thursday reaction to the minutes, which left real yields higher and share prices lower than they were before Powell’s alleged rookie mistake on Oct. 3, seems to be about right.

Authers notes:

Klarman Hall: Legendary value investor Seth Klarman (who heads Baupost Group) just had a building named after him at his alma mater, Harvard Business School. At its opening, he made a brilliant speech about the problems with capitalism, which you can read here, and which I would recommend to anyone with a few minutes to spare.

Some brief highlights included this admonition to an audience we can assume was overwhelmingly pro-capitalist:

We should all keep in mind that the benefits of capitalism are not so obviously and directly attributable to the system the way the adverse side effects and increasing societal inequality are. The invisible hand is, by definition, invisible.

He also offered this masterly rebuke to those who still believe in shareholder capitalism:

Chainsaw Al Dunlap, a real person with a Hollywood moniker, told us that a dollar earned by killing a job was just as valuable as one earned by producing a valuable product, and Wall Street was seduced, even though it’s obvious that you can’t cut your way to prosperity. It’s also apparent that a dollar of earnings generated through business expansion may be an annuity, and perhaps even a growing one, while a dollar gained from cost savings is a one-time improvement, an incremental cash flow that is not replicable and one that may even come at a greater cost — short- and long-term, financial and otherwise—than is readily apparent.

If anyone doubts the relevance of this, bear in mind that General Motors’ stock rallied strongly this week on the day it announced sweeping layoffs and plant closures. It’s worth reading Klarman’s speech, and it’s great that Harvard gave him a pulpit to make these points.

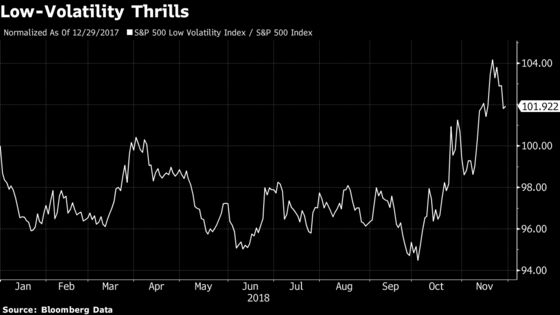

Low-Vol, High-Return: There were few victors from the October sell-off, but the low-volatility style of investing might just be one of them. In general, I am not a fan of “low-vol” investing, which is popular as a style that limits the damage during doses of high volatility. It has never been clear to me that this makes up for rather dull performance the rest of the time.

In the February selloff, my cynical view was upheld. Low-vol outperformed slightly, but not by enough to catch up. The S&P 500 Index remained well ahead for the year as a whole. But the October selloff was different, with S&P’s Low-Vol index beating the S&P 500 by as much as 10 percent at one point. It has been pegged back this week, but remains ahead for the year, and did its job in October.

If you expect a further resurgence of volatility next year, a popular and eminently reasonable call, then the low-vol might make sense.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.