(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It was with great sadness that I learned that Princeton University economist Alan Krueger had died over the weekend at the age of 58. In his outstanding but too-brief career, Krueger helped turn the economics profession into a more empirical, more scientific enterprise. His research shed light on many of the most important policy issues facing the U.S., and he put that knowledge to good use working for two presidential administrations. He will be greatly missed.

I first met Krueger at a conference called the Princeton Data Improvement Initiative, back in 2008. The conference’s theme was how to make empirical economics research more credible. I was instantly impressed by Krueger’s tireless, patient attention to the details of both data sets and research methods. Some economists tend to trumpet their own work; others strenuously argue against methods that lead to implications they don’t like. But Krueger was always a beacon of cool-headed reason -- his overriding goal was to get the facts.

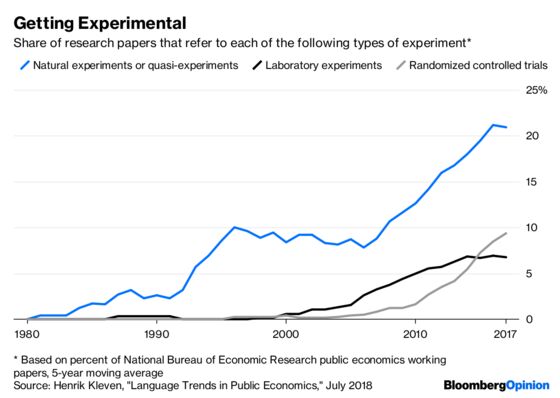

That respect for evidence made Krueger an important voice in an economics profession in the midst of rapid change. In recent decades, the theory-heavy economics of the 1970s and 1980s has given way to more empirical approaches. The most important change has been what economists Joshua Angrist and Jörn-Steffen Pischke call the “credibility revolution” -- using carefully designed studies to isolate cause from effect, instead of simply looking at correlations or relying on a theoretical model that might be wrong. Two types of such studies include natural experiments, in which policy changes or random variations in economic conditions allow economists to tease out causation, and randomized controlled trials, in which researchers actually test policies to see if they work:

Krueger himself was a key figure in this revolution, helping to pioneer the use of natural experiments. His landmark study, written with David Card, was a 1994 paper evaluating the results of a rise in New Jersey’s minimum wage. Traditionally, economists believed that minimum wages caused a substantial degree of job loss -- this was based on the textbook model of supply and demand, which says that placing a floor on the price of something causes a shortage. Card and Krueger, however, suspended judgment on that theory and simply compared employment changes at stores in New Jersey to changes at stores in nearby Pennsylvania, which hadn’t raised the minimum wage.

Card and Krueger’s result shocked the economics world -- the higher minimum wage had no effect on employment, at least in the short term. A large number of follow-up studies found similar results for a number of minimum-wage experiments. The economics profession was faced with an unusual case where the facts were clear enough to present a challenge to a long-accepted textbook theory. Slowly, economists are being forced to do what natural scientists would do in this situation -- look for another theory to explain how labor markets work. Some are converging on the theory of monopsony power as a simple alternative, while others are building more complex, realistic models.

The minimum-wage study, though well-known, was hardly Krueger’s only major contribution to empirical economics. His research often focused on other determinants of wages and employment, such as occupational licensing, unemployment insurance and European labor-market regulations. When he died, he was in the process of studying whether President Donald Trump’s tax cuts had boosted wages or employment (answer: unlikely).

Krueger also did a lot of research on education. In a study of identical twins written with Orley Ashenfelter, he found that the quality of schools has a large impact on earnings, and another of his papers found evidence that smaller classes are better. But in a paper with Pei Zhu evaluating a New York City program, Krueger found that school choice tends not to improve student outcomes (except possibly for African-American students).

Krueger’s range was so broad that he even wrote a book on the economics of terrorism and a paper (with Marie Connolly) on the economics of rock and roll.

Nor did Krueger restrict himself to the academy. He served as the chief economist at the Department of Labor under President Bill Clinton, assistant Treasury secretary under President Barack Obama, and then chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers later in the Obama administration.

In many ways, Krueger’s work defined what a modern economist should look like. He relentlessly focused on issues of practical, immediate importance. He constantly concerned himself with the betterment of the lives of poor and working people, but refused to naively assume that programs designed to help these people always had the intended effect. He was always aware of relevant economic theories, but never let himself be bound by them. This eclectic, humble, humanistic but practical approach has set the tone for an entire generation of young economists.

He was taken from us far too soon, but his impact on economics, and on the world, will last for a very long time to come.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Greiff at jgreiff@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.