(Bloomberg Opinion) -- It’s said that British politicians care only about one subject right now, but besides Brexit there’s at least one other mess that needs sorting out quickly: The poor quality of company audits. While this may sound like a dry topic, it has ugly real-world implications. Just look at the collapse this week of cake chain Patisserie Valerie’s owner after an accounting scandal, an event that puts as many as 2,800 jobs at risk.

While Patisserie Holdings Plc appears to have been the victim of fraud, there have been other high-profile British accounting blowups recently involving retailer BHS and government contractor Carillion Plc. They had equally dire consequences for workers and investors.

In wealth destruction terms, none of these calamities compares to the collapse of Enron and Worldcom (and their auditor Arthur Andersen) more than 15 years ago, which led to the Sarbanes-Oxley financial reforms and independent oversight of the audit industry. But they do beg the same question: “What on earth were the auditors up to?” and “How does a company implode so soon after receiving a clean audit opinion?” General Electric Co’s fall from grace shows this isn’t just a British problem right now.

The upshot is that there’s a political consensus in Britain that the audit profession needs comprehensive reform (again). The U.K. has launched half a dozen (yes, six!) reviews of the industry to address things like the lack of audit competition, impartiality issues arising from selling both audit and consulting services to clients, plus ineffective regulation.

Arguably, though, Britain is only just starting to address the most important question of all: What is the purpose of an external audit and are auditors really doing what we expect of them? A government-backed review, chaired by the departing chairman of the London Stock Exchange Donald Brydon, is exploring this issue and it’s one that shouldn’t just be of interest to academics.

If you ask a member of public what auditors do, they’ll tell you – not unreasonably – that the job is all about seeking out fraud and preventing a company from going bust. In reality, though, the auditor’s remit is much more limited. They’re watchdogs, not bloodhounds, to paraphrase a century-old legal judgment.

Auditors provide “reasonable assurance”, but no cast-iron guarantee, that the accounts are free of material misstatement. Their work is inherently backward-looking and cannot entirely preclude fraud, or future insolvency, the industry says. “While a company might fail following issuance of an unqualified audit opinion, this does not automatically mean the auditor did a bad job,” KPMG’s U.K. chairman Bill Michael told the Carillion inquiry. This so-called “expectations gap” is a decades-old excuse for auditors when companies run into trouble.

In fairness, company directors are the ones who bear legal responsibility for preparing financial statements, not the auditors, who provide an opinion on whether the accounts give a true and fair view. Indeed, Britain’s cosy boardrooms could probably do with a reminder of that fact. Sarbanes-Oxley obliged their American peers to personally certify the accuracy of financial reports (deliberately signing off on a false set of U.S. accounts is punishable by up to 20 years imprisonment). Deloitte and EY are among those calling for a Sarbanes-Oxley equivalent in the U.K.

“If your house gets burgled, the crooks are the ones who burgled you, not the police who failed to catch them,” says Paul Merison, a lecturer at the London School of Business & Finance. That doesn’t mean we should let well-paid auditors off the hook, though. The thinning out of investment analyst coverage of small companies after Mifid II makes it even more critical that auditors keep a watchful eye on behalf of shareholders.

How then can we close that expectations gap? Part of the answer is for auditors to become more like bloodhounds and for audits to become more transparent, and forward-looking. For starters, auditors aren’t clearing even the very low bar they set themselves. More than a quarter of audits reviewed by the U.K. regulator, the Financial Reporting Council, were found to be unsatisfactory. And that might understate the problem.

Grant Thornton’s audit work on Patisserie Holdings was given a clean bill of health by the regulator prior to the chain’s collapse, The Times has reported. Yet the chain now says there were “thousands of false entries” in its ledgers, something you’d hope an auditor would spot. The FRC singled out KMPG for criticism last year, saying its audits were “unacceptable” and its auditors hadn’t used enough professional skepticism (Carillion was a KPMG client). The FRC’s review of what happened at BHS also makes uncomfortable reading for PwC.

Again, this isn’t just a British problem; U.S. audit inspections carried out by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board frequently show serious deficiencies.

Improving audit quality would also mean answering some more basic questions. “What is the point of audit if it cannot or will not flag up fundamental weaknesses or risks in a company's finances?” Rachel Reeves, a lawmaker, asked in November. It’s not just politicians who worry about missing the wood for the trees. In evidence to another of Britain’s many audit inquiries, asset manager Sarasin and Partners made the following pertinent observation:

“Put simply, auditors are providing the wrong (or only a partial) service by focusing on checking whether companies are complying with accounting standards. Their core function should be assessing whether capital is being properly protected.”

Fortunately, there have been some improvements. Since 2013, British auditors have had to spell out so-called “key audit matters” in a company’s annual report. These are areas where there’s a significant risk of misstatement or that involve a lot of management judgment. In other words, “what kept the auditor awake at night.” These reforms have since been adopted more widely and U.S. companies will start doing similar this year.

This is a good start, but audit reports are still too black and white. Instead of a simple pass/fail test, auditors could tell shareholders whether a financial estimate was “cautious,” “balanced” or “optimistic.” KPMG, which developed this “graduated findings” approach, wants to make it mandatory for FTSE 350 audits. Its detailed audit of Rolls-Royce Holdings Plc’s accounts shows how it might work.

Something else worth considering is forcing management to provide more color on whether cash and capital resources are sufficient to remain a going concern, and for auditors to highlight any shortcomings or caveats to that statement, as the Nationwide Building Society proposes. Such disclosures might alert shareholders to potential vulnerabilities and discourage companies from piling up debt, neglecting pensions and paying dividends out of profits that only exist on paper.

A related idea is to establish a “duty of alert,” obliging auditors to report financial viability or other serious concerns to the board, or to shareholders or the regulator.

Of course, there’s not much point in auditors disclosing more information if investors don’t read it. Shareholders have “little engagement with audit matters” and their votes on auditor appointments are a “formality,” the Competition and Markets Authority says. Among the key audit matters highlighted by Deloitte in disgraced South African retailer Steinhoff International’s last full accounts were the valuation of goodwill and M&A accounting. But investors didn’t pay much attention until Steinhoff blew up.

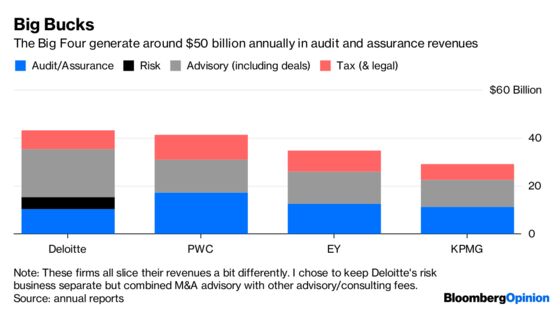

It’s possible that making audits more stringent will make them more expensive. Adding complexity to the process might also discourage smaller audit firms from trying to compete – the opposite of what the government wants. To anyone familiar with the Big Four’s stranglehold, such an outcome wouldn’t be remotely surprising.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies. He previously worked for the Financial Times.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.