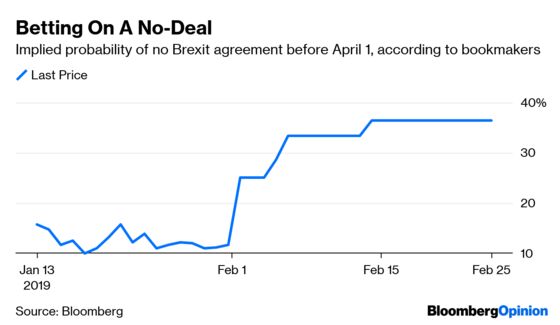

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Moderate British lawmakers are hoping they can kill the threat of a no-deal Brexit in a parliamentary vote this week. But the prospect of the U.K. crashing out of the EU without an agreement on March 29th is like the monster that never dies: Bookmakers still rate the chances of this unhappy outcome at close to 40 percent.

Officials in Brussels have certainly become more gloomy about “no deal.” Prime Minister Theresa May has no new sweetener from the EU to hand to her divided Conservative Party, nor to Parliament as a whole. Many lawmakers are hoping for a long extension of the departure negotiations, but that would almost certainly spell the end for May’s time in office. As such, it’s hardly surprising that she’s sticking to her “running down the clock” approach, which would end up with Parliament being offered the choice of either supporting some version of her withdrawal deal or letting a hard break happen at the end of March.

For someone with a reputation for extreme caution, it’s a remarkably reckless gambit. Nobody is truly ready for “no deal,” neither in the U.K. nor the rest of Europe.

There are, of course, no-deal laws and contingency plans designed to offset the damage of Britain leaving the single market, customs union and more than 750 international agreements overnight. Yet many of them rely on political trust and reciprocity, such as whether the U.K. sticks to its word on guaranteeing the rights of EU nationals on its soil. The no-deal plans as a whole are temporary, stopgap measures. And they haven’t all been passed yet.

The big unknown is trade. Consider Ireland, probably the EU country most exposed to Brexit given its ties to the U.K., which in 2017 sent 34 billion pounds ($44.5 billion) of exports to the republic and received 21.8 billion pounds of imports. Ireland’s own contingency plans for “no deal” have more detail on driving licences than on what the border with the U.K. would look like. Everyone agrees there would be tariff and non-tariff barriers without a Brexit deal, but nobody wants to be held responsible for enforcing them.

The hard-line Brexiters among May’s lawmakers have rejected her deal because of the so-called “backstop,” which guarantees the absence of a hard border between Ireland and Northern Ireland. But a no-deal Brexit would hardly solve the problem. Despite the tendency of Brexiters to shrug off the Irish border as unimportant, it could easily become a toxic crisis. Nobody believes Brussels or Dublin would suddenly throw up land checkpoints or send border guards, but they might choose to implement checks on goods leaving or heading to the island of Ireland as an alternative. A potential hard border would fuel calls for a poll on Irish unification.

And Ireland is only one of many huge worries for no-deal planners. It’s been widely assumed that Europe’s banking infrastructure is well-primed for a disorderly Brexit; recent regulatory proposals to offer temporary “equivalence” on finance rules between the bloc and the U.K. – ensuring cross-border access to market infrastructure – are obviously a big help. But the thicket of rules means nobody can rule out unforeseen difficulties. Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc, for example, has warned that it might not be licensed in time to keep handling 50 billion euros ($57 billion) of daily euro-denominated payments. Individual countries are trying to preserve contract continuity and cross-border financial services, but this isn’t an EU-wide initiative yet.

Then there’s the risk to the EU’s finances. Britain has agreed to pay 39 billion pounds to Brussels as a condition of its leaving. Would that commitment be kept in a no-deal scenario, especially if the ruling Conservatives chose a Brexiter such as Boris Johnson as their next leader? There are sound reasons to keep paying but, depending on how febrile the political and economic environment becomes, Britain might change its mind. That would bring its own tit-for-tat responses, which again could get ugly. What would begin as a cut to EU-financed projects in the U.K. might lead to member states scrambling to withdraw their gold stored at the Bank of England.

Former WTO chief Pascal Lamy says a no-deal Brexit is like “jumping off a cliff without a parachute.” He’s right. But, even as Parliament wrangles, the launch date is only getting closer.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Boxell at jboxell@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Lionel Laurent is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Brussels. He previously worked at Reuters and Forbes.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.