Mild Omicron and an Aggressive Fed May Hurt Gold

Topics

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Could a dose of mild omicron plus aggressive action by the Federal Reserve sicken gold? This week’s sell-off in Treasuries may be more of a tizzy than a tantrum. But the recent rise in real interest-rate indicators, even if from subzero levels, spells trouble for gold bulls. After all, we’ve been here before.

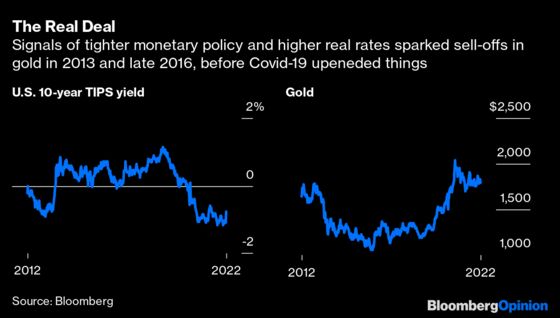

Gold likes abnormality — such as abnormally lax monetary policy and its associated narratives of hyperinflation, economic chaos and everyone eating cold beans from a can. Conversely, signs of normalization tend not to go down too well. Hence, 2013’s initial taper tantrum and, at the end of 2016, the bump in the federal funds target rate above half a percentage point sparked sell-offs. Yet Covid-19’s sudden intervention at the end of a decade of ultra-easy monetary policy upended things again. Last summer, gold briefly shot above $2,000 an ounce, an all-time high.

The return of inflation should, in theory, boost the price of gold. But there are complications.

As my colleague Brian Chappatta wrote here, last week’s sell-off in Treasuries can be read as a “hopeful message” about the latest wave of Covid-19: While the surge in case numbers portends disruption, the omicron variant appears to cause fewer hospitalizations and deaths. Results from a study published Friday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention add further evidence that vaccination sharply reduces the risk of severe outcomes from infection.

So while the disruption caused by workers staying home after testing positive should keep near-term inflationary pressures up, it shouldn't turn 2022 into “2020 II,” with all the economic havoc that would entail. In other words, this is an environment in which the Federal Reserve can make good on its suddenly tougher talk about inflation without endangering the recovery.

Even Friday’s nominally bad jobs numbers should be viewed in the context of just how weird conditions are right now. The unemployment rate dropped below 4% even as hiring was subdued. More important, wage inflation of 4.7% came in half a percentage point above already elevated expectations. Treasury yields, taking their cue from that news rather than the headline payrolls number, pushed higher.

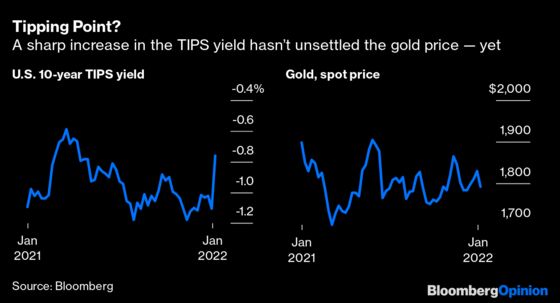

For gold — and, let’s face it, pretty much every asset class — the big question concerns the speed of normalization and whether another, nastier variant (or some other disaster) shows up. The recent uptick in real rates, as indicated by the yield on inflation-protected Treasuries, or TIPS, is small enough that it may be seen as just another fluctuation below zero, leaving gold relatively unperturbed. Fed funds futures, on the other hand, indicate roughly an 80% probability of an interest-rate increase as soon as March. This week’s inflation data and Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s first Senate appearance of the year should provide further clues on that.

Meanwhile, Chris Watling, who runs Longview Economics, a London-based research firm, points to a breakdown in the relationship between the TIPS yield and forward interest rates implied by Eurodollar futures. Typically, these track each other quite closely, but the Eurodollar implied rate is now in positive territory and more than 1 percentage point higher. He expects the TIPS yield to “catch up” as evidence of economic recovery mounts. When it does, the price of gold, so far resistant to the ripples in the Treasury market, may catch up, too — by moving down.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.