(Bloomberg Opinion) -- I can’t open a web browser lately without seeing a banner promoting State Street Corp.’s new digital series “Crazy Enough to Work” starring actress Elizabeth Banks — who, I must confess, I think is fabulous.

The series profiles four midsize companies. The first two episodes showcase EPR Properties and the New York Times Co. and have already been released. The final two feature Dunkin’ Brands Group Inc. and the Boston Beer Co. and will be available on Aug. 29 and Sept. 12, respectively.

It’s all a plug for State Street’s SPDR S&P MidCap 400 ETF, which makes me wonder about those algorithms supposedly customizing my online experience. I’ve never expressed any interest in buying a mid-cap stock fund.

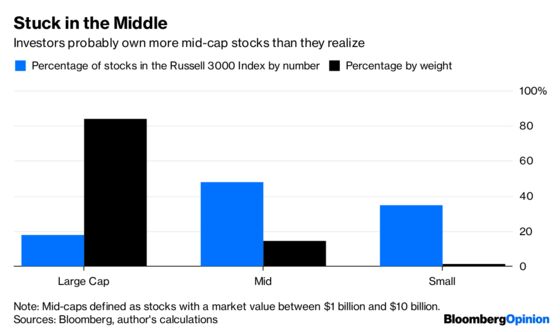

It’s not that I have anything against mid-caps. On the contrary, I own them like nearly everyone else. I’m defining mid-caps as stocks with a market value of $1 billion to $10 billion. If you own a large-cap stock fund, chances are you own some mid-caps, too.

Consider that there are 458 mid-cap stocks in the Russell 1000 Index, which collectively make up 8.9 percent of the index. Mid-caps make up an even bigger chunk of the broader market. There are 1,429 mid-caps in the Russell 3000 Index, accounting for 14.6 percent of the index.

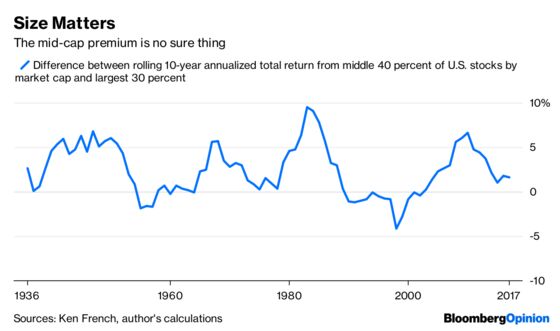

The question, therefore, isn’t so much whether to own mid-caps, but how much to own. There’s evidence that midsize companies deliver higher returns over time. According to numbers compiled by Dartmouth professor Ken French, the middle 40 percent of U.S. stocks by market cap — which closely approximates the mid-cap universe — outpaced the largest 30 percent by 2 percentage points a year from July 1926 through June, including dividends.

That premium makes intuitive sense. Midsize firms have fewer resources than large ones and are more vulnerable during downturns. Their stocks are also more thinly traded, which makes them more costly and difficult to sell, particularly during a downturn. And they’ve been 30 percent more volatile than large caps over the last nine decades, as measured by annualized standard deviation. Who would take on those additional risks if mid-caps didn’t pay more?

Still, it’s not clear that the reward will be as generous going forward. For one thing, the premium has declined since the early 1980s when academics first spotted it. Those middle 40 percent of stocks outpaced the largest 30 percent by 2.5 percentage points annually from July 1926 to December 1979. But since 1980, it has shrunk by nearly half to 1.3 percentage points, which suggests that mid-caps have become more popular since their premium was discovered.

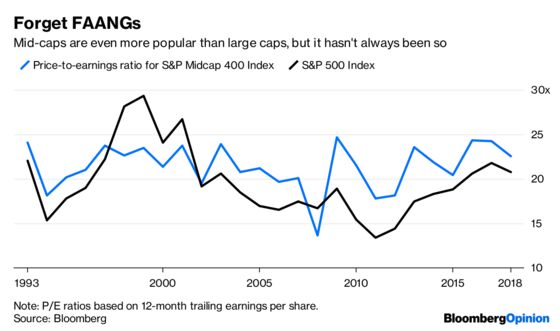

There’s some evidence for that, as well. The price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P Midcap 400 Index has been higher than that of the S&P 500 Index 80 percent of the time since 1993, the earliest year for which numbers are available for both indexes, based on 12-month trailing earnings per share.

And those richer prices have kept a lid on premiums. During periods when mid-caps were more expensive than large caps from 1993 to 2007, the subsequent 10-year premium averaged 2.2 percentage points a year. But when mid-caps were cheaper, the average premium jumped to 5.7 percentage points. It’s a small sample, but it jibes with longer-term data showing a correlation between high prices and lower subsequent returns, and vice versa.

What’s surprising is that, despite the huge popularity of large companies such as Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Google parent Alphabet, mid-caps are even more expensive than large caps. The P/E ratio of the mid-cap index is 22.6, compared with 20.8 for the S&P 500. That’s in line with the average difference since 1993.

I think you’ll enjoy State Street’s stories about the vision and grit of midsize companies. Just don’t assume that mid-cap stocks will provide the same magic.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Nir Kaissar is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the markets. He is the founder of Unison Advisors, an asset management firm. He has worked as a lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell and a consultant at Ernst & Young.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.