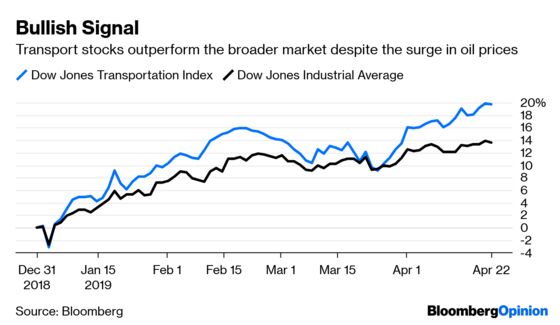

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The price of oil surged as much as 3 percent Monday after the Trump administration said it would not renew waivers that let countries buy Iranian oil without facing U.S. sanctions. Logically, this should have hit the equity markets pretty hard. After all, with all the talk about a looming recession, companies and consumers surely wouldn’t be able to weather a rise in energy prices. But in a sign that perhaps the economy is doing just fine, equities managed to hold up fairly well.

The biggest “up arrow” came from the Dow Jones Transportation Average, whose members include railroad Norfolk Southern Corp., package delivery company FedEx Corp. and trucking firm J.B. Hunt Transport Services Inc. The one sector that should be hit hard from rising oil prices was little changed on the day, bringing its year-to-date gain to 19.7 percent, which outpaces the 13.7 percent surge in the more diverse Dow Jones Transportation Average. As for the economy, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow Index, which aims to track growth in real time, has risen to 2.79 percent from a “stall speed” level of 0.17 percent in mid-March. While that’s not above the 3 percent level desired by the Trump administration, it’s a respectable number given that inflationary pressure — at least as measured by the government — is nowhere to be seen. And although the S&P 500 Index is less than 1 percent from its record closing high set in September, more and more strategists are saying the recent rebound has room to run if for no other reason than there is so much pessimism toward equities and the economy. In a report titled “‘Wall Of Worry’ Taller Than Trump’s Border Wall!”, Leuthold Group Chief Investment Strategist Jim Paulsen points out that a broad measure of market concern is as high as it has ever been since 1970. And that’s a good thing for equities, with average annualized returns of about 18.5 percent in the following 13 weeks compared with 10.5 percent the rest of the time.

The measure Paulsen references is the price of gold relative to the broader commodities market divided by the price of small capitalization stocks relative to the S&P 500. “Overall, this bull market has epitomized the power of a ‘Wall of Worry,’” Paulsen wrote in a research note. “Born without buyers and driven by reluctant investors gaining participation by cautiously nibbling only at its most defensive corners.”

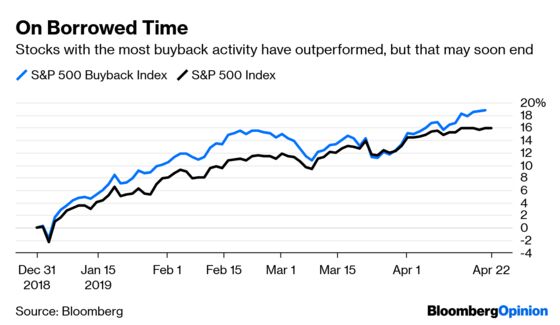

BUYBACKS MAY BE A DYING BREED

That’s not to say there isn’t plenty for equity investors to be worried about. Perhaps the biggest concern is the potential for a marked slowdown in share buybacks, especially if a sluggish economy prompts corporate executives to redirect cash toward deleveraging. At the heart of the issue is the more than doubling of the size of the U.S. investment-grade debt market since 2008 to about $5 trillion. About half is composed of bonds in the triple-B tier — those with BBB+, BBB or BBB- ratings — which have more than tripled. It’s here, in the lowest investment-grade category, where investors are most worried because anything rated BB+ or lower is considered junk. The strategists at Bank of America pointed out in a research note Monday that of the 45 percent growth in earnings per share for members of the Russell 3000 index — excluding financials, utilities and real estate sectors — some 12 percentage points could be attributed to buybacks. “Late 2018 was the turning point in this cycle of expanding debt balance sheets, buying growth and rewarding shareholders, in our opinion,” the Bank of America strategists wrote. The combination of rising interest rates and the broad “market dislocation” in the fourth quarter “played the role of a wake-up call to the largest bond issuers,” they added, pointing out that the yield spread on the bonds for many issuers rated BBB widened to more than 2 percentage points, which is a level usually reserved for junk bonds. “Today, the game has changed. Three times as many investors want companies to pay down debt than to buy back stocks, and the cost of equity capital reflects this: the relative multiple of levered companies (versus) cash-rich companies is now at a 7 (percent) discount to history.”

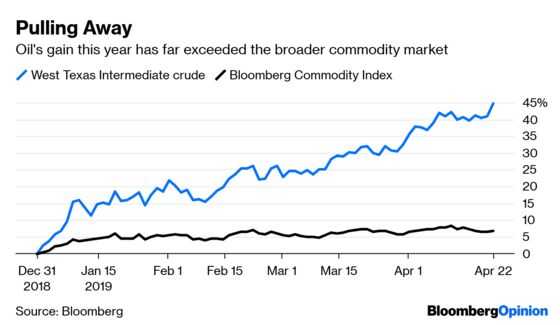

OIL DELIVERS WIN TO HEDGE FUNDS

The rally in oil Monday brought to 54 percent the gain in West Texas Intermediate crude since its late December lows. And for what seems the first time in a long time, hedge funds are getting it right when it comes to betting on oil. Money managers boosted optimistic wagers on West Texas Intermediate crude to the highest since October in the week ended April 16, according to Alex Nussbaum and Caleb Mutua. U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission data released Friday showed the net-long WTI position— the difference between bets on higher prices and wagers on a decline — rose 10 percent to 303,366 futures and options contracts. Long positions climbed 8.4 percent while shorts declined 6.5 percent. Another way to look at this is that hedge funds are betting against President Donald Trump. In the wake of the move against Iran, Trump tweeted that “Saudi Arabia and others in OPEC will more than make up” for any drop in supply from Iran. Saudi Energy Minister Khalid Al-Falih said the Saudis would coordinate with fellow producers to keep adequate supplies available to consumers while ensuring the oil market “does not go out of balance.” Both Saudi Arabia and the U.A.E. are ready to boost output to offset any drop in output from Iran and can increase their combined production by about 1.5 million barrels a day within a short period, Bloomberg News reported. The additional oil would more than compensate for losses from Iran, which shipped about 1.1 million barrels a day of crude and condensate in the first half of April. To be sure, Trump has tweeted a number of times in the past year or so that OPEC needs to boost production, but the cartel has actually been quite successful in cutting supplies to support prices.

BOND TRADERS AREN’T WORRIED. YET.

The big issue for the bond market whenever oil spikes higher is whether the move will prove to be inflationary or a drag on growth. For now, yields are suggesting it’s the latter. Despite WTI prices reaching almost $67 a barrel on Monday, the highest since October, breakeven rates on five-year Treasuries — a measure of what bond traders expect the rate of inflation to be over the life of the securities — are only their highest since last month at 1.88 percent. In October, they were above 2 percent. The most immediate impact on consumers will be at the pump, where prices for a gallon of regular grade gasoline have risen to an average of $2.84 heading into the all-important summer driving season, according to the Automobile Association of America, up from January’s low of $2.23 a gallon. This wouldn’t be too hard for consumers to weather in a robust economy with rising wages, but that’s not happening. The U.S. government’s monthly jobs report showed that average hourly earnings rose just 0.1 percent in March, below the 0.3 percent increase that was forecast by economists. And on Friday, the government’s report on gross domestic product for the first quarter is forecast to show that personal consumption grew at a sluggish 1 percent pace. If true, then the only quarter lower since 2013 would be the first three months of 2018, when consumption rose by just 0.5 percent. To be sure, the bond market isn’t overly complacent about the inflationary impact from rising oil prices. Breakeven rates have jumped from this year’s low of 1.48 percent in early January, tracking the rise in oil prices higher fairly closely.

SRI LANKA SUFFERS

The bombings in Sri Lanka come at a sensitive time for that country’s economy and may threaten to derail the first sustained appreciation in its currency since the end of a civil war in 2009. The rupee had gained 5.05 percent this year through Friday. The last time the rupee showed an annual gain was in 2010, when it appreciated 3.01 percent, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. “The rupee is a heavily managed currency and is subject to sharp periodic adjustments,” the strategists at Brown Brothers Harriman wrote in a research note Monday. “We think this will be one of those times. With foreign reserves very low right now, the central bank cannot actively support the rupee if it comes under severe pressure when markets reopen.” The bombings, together with rising political tension and slower economic activity, will probably weaken the currency to about 180 a dollar, Bloomberg News reported, citing Gulf Investment Corp. in Kuwait City. That would be a decline of nearly 3 percent from last week’s close of 174.11 per dollar. At around $5 billion in February, Brown Brothers notes that Sri Lanka’s reserves are the lowest since April 2017, a level that barely covers two months of imports and represents about two-thirds of the nation’s stock of short-term external debt. The economy grew 1.8 percent in the fourth quarter from a year earlier, and the bombings will create even more downside on growth because tourism accounts for about 5 percent of gross domestic product, according to Brown Brothers Harriman. Central bank Governor Indrajit Coomaraswamy told Bloomberg TV that any likely bond-fund outflows from the island nation would be “manageable” and that Sri Lanka would be able to meet its debt obligations.

TEA LEAVES

After a brief respite in February as pent-up demand from the government shutdown was unleashed, it looks as if U.S. housing is weakening again. First, the government said Friday that U.S. new-home construction fell unexpectedly in March, decelerating to the slowest pace since May 2017. Then on Monday, the National Association of Realtors said that sales of previously owned homes eased more than forecast in March. And on Tuesday, the government is forecast to say that new home sales dropped 3.6 percent in March after February’s 4.9 percent gain. Any way you cut it, the economy needs a strong housing market to avoid a recession. But the fact that sales are sluggish at the time of year when they should be strong — and with mortgage rates relatively low — should be a warning sign.

DON’T MISS

What’s Missing for a Market ‘Melt Up’: Mohamed A. El-Erian

Traders’ Favorite Villains Deserve a Big Thank You: Daniel Moss

Selfie Deaths Are Like Stock-Market Crashes: Barry Ritholtz

Perishable Money Is an Old Tool to Fight Recession: Stephen Mihm

On Iran Sanctions, Saudis Will Trust But Verify: Liam Denning

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Robert Burgess is an editor for Bloomberg Opinion. He is the former global executive editor in charge of financial markets for Bloomberg News. As managing editor, he led the company’s news coverage of credit markets during the global financial crisis.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.