I’ll Have a Side of Gucci With My Common Prosperity, Please

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Common prosperity — the policy directive du jour of President Xi Jinping — won’t banish luxury goods from Chinese malls. But it will usher in a new era where watches are encrusted with fewer diamonds and logos no longer embellish jackets and jewelry.

Earlier this year, Beijing laid out a proclamation to build an “olive-shaped” society with a more equitable distribution of wealth. That's been followed by regulatory crackdowns on big industries like consumer tech companies and the online education sector. While state planners have long talked about the Chinese population being moderately prosperous, the government’s single focus is to steer the country away from a winner-takes-all economy.

In doing so, much of the rhetoric around common prosperity is centered on bettering health care, growing household incomes, increasing benefits and using taxes to calibrate income distribution. It’s not the sort of environment conducive to flashy buys. For the big luxury groups, bolstered by five years of surging demand from Chinese consumers, it will require a reassessment of their aesthetics, products and marketing.

Against this backdrop, luxury is likely to be characterized by more subtle designs, with fewer ostentatious details. We could see a return to the mood that engulfed China almost a decade ago, amid a crackdown on corruption, when consumers didn’t want to make their consumption too conspicuous. Products like watches and high-end alcohol were collateral damage.

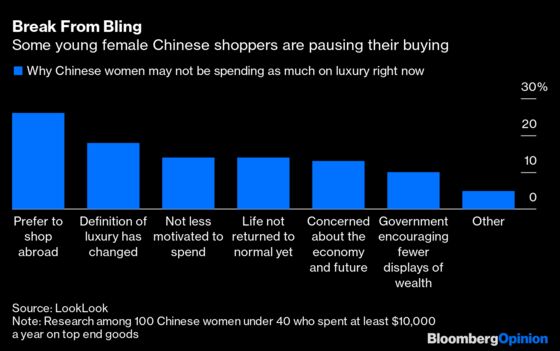

Already some young Chinese shoppers are pausing their passion for luxury, according to research from LookLook, an insights group that conducted research in September among 100 Chinese women under 40 who spend at least $10,000 a year on top end goods. They are primarily holding back in anticipation of traveling – and spending – outside of China again. But one in 10 said they had been influenced by the government’s stance against excessive shows of wealth. Jia Lin, analyst at LookLook said she was surprised to hear some of the young women wanting to keep a low profile.

Given the new mood, those houses with more discreet designs, such as Prada SpA, and Kering SA’s Saint Laurent and Bottega Veneta look well placed. Alessandro Michele, creative director of Gucci, is already adjusting his trademark maximalism to appeal beyond the brand’s millennial fanbase. Recent collections have been more understated. But further work may be needed to align with the new zeitgeist: The Gucci name and logo are still very much in evidence. Getting the tone right matters to parent Kering. In 2019, Gucci accounted for about 60% of sales and about 80% of operating profit.

But there are other ways the industry needs to adapt.

If common prosperity induces anxiety at the very highest echelons, but expands the middle class, that could drive demand for entry-level handbags, costing around $1,000, rather than those made from exotic skins costing at least 10 times more. Brands will need to “really look after the first-time buyer as well as the billionaire,” says luxury adviser Mario Ortelli.

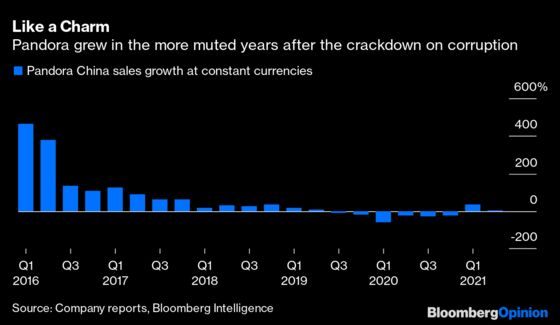

Small leather goods could get a boost, as well as affordable treats such as beauty and fragrance. That would be good news for the global cosmetics giants. Pandora AS, best known for its cheap charms, enjoyed strong growth in the wake of the anti-corruption campaign.

LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton SE’s flagship Louis Vuitton brand, with its distinctive monogram, is vulnerable to any move away from instantly recognizable labels. But this could be offset by its product range, which starts at the relatively affordable Neverfull bag, for example. LVMH also generates a quarter of its sales in the U.S., where consumers are still snapping up Rolex watches and Moncler coats.

The flipside of the new mood is appealing to a more woke, new-age Chinese consumer. Reaching these buyers is no longer as easy as a bold logo or an ubiquitous social media presence. Big brands will need to hone marketing techniques like collaborating with key opinion leaders, or KOLs, live-streaming on shopping platforms and using virtual KOLs. They’d also have to think of running their own shows online. The social e-commerce market is estimated to be worth 1.2 trillion yuan ($186 billion) this year from 961 billion yuan in 2020, according to HSBC Holdings Plc analysts.

China has a thriving influencer economy but choosing and leveraging the right KOLs has become more crucial. That is because Beijing is pushing away from fan culture and certain types of gender imagery.

Brands are trying different offline formats, too. Prada, for instance, got creative and took over a local market in Shanghai to wrap basic food items in the company’s packaging. Local audiences loved it. Other brands are tapping into social issues. To do this well, they’ll have to ensure they have their fingers on the local pulse.

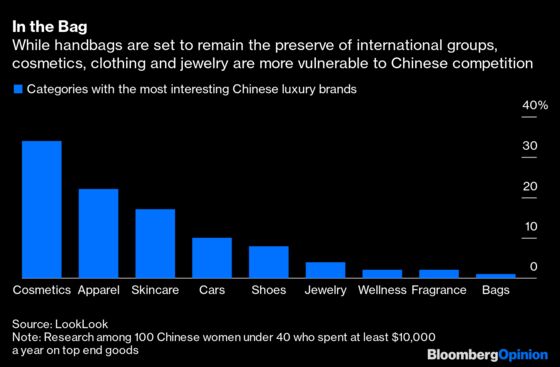

But perhaps the biggest risk is that the current mood sees Chinese shoppers turn away from the global giants to homegrown luxury. Handbags are likely to remain the preserve of the European houses. But local players such as Cindy Chao are gaining traction in jewelry. Chinese brands are also making headway in beauty and fashion, according to LookLook.

Such shifts are unlikely to show up in forthcoming third-quarter results. But a resurgence of Covid cases and a slowing Chinese economy may well do. At least that gives the luxury behemoths more time to reinvent themselves if stealth wealth rather than bling becomes the hottest look.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Andrea Felsted is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the consumer and retail industries. She previously worked at the Financial Times.

Anjani Trivedi is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Asia. She previously worked for the Wall Street Journal.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.